Happy Robert Burns Day!

Perchance you’ll be supping on “warm-reekin, rich” haggis in yer luggies this wonderful Burns nicht, in celebration of the Scottish poet’s birth 253 years ago.

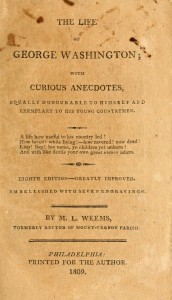

If so, or even if not, consider the story of the “Stinking Edition.”

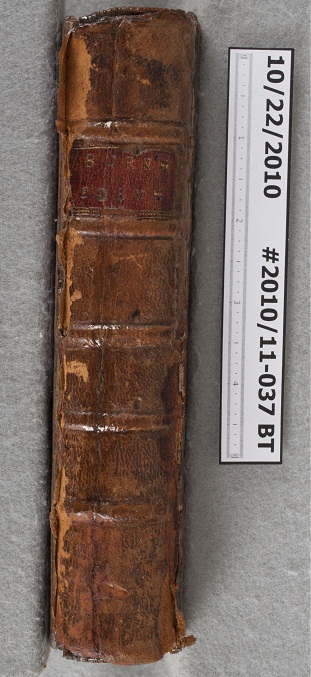

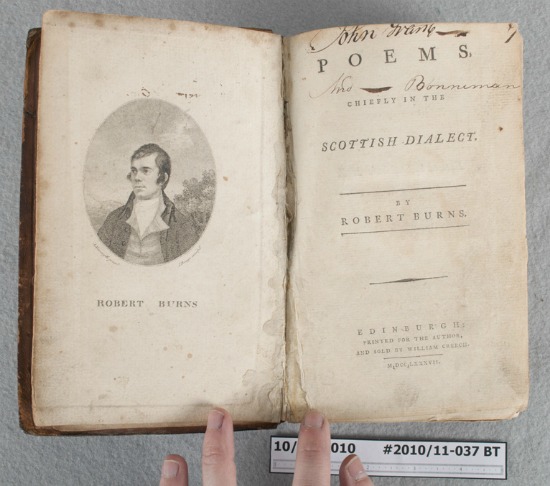

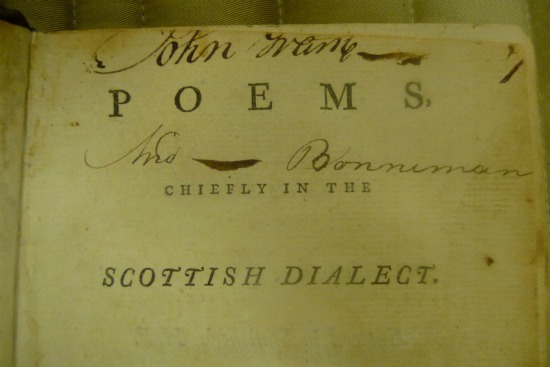

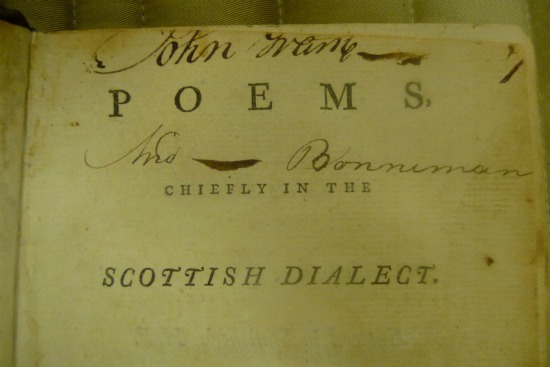

The first volume of poems by Robert Burns, Poems, Chiefly in the Scottish Dialect, was published on July 31, 1786, in Kilmarnok. On the strength of this edition, a second, enlarged edition was planned and published on April 17, 1787 in Edinburgh.

This edition featured an unfortunate misprint in the excellent poem “To a Haggis.” In the last stanza of the sausagey poem, the adjective “skinking,” which means “watery,” was printed as “stinking,” which obviously means “stinking.”

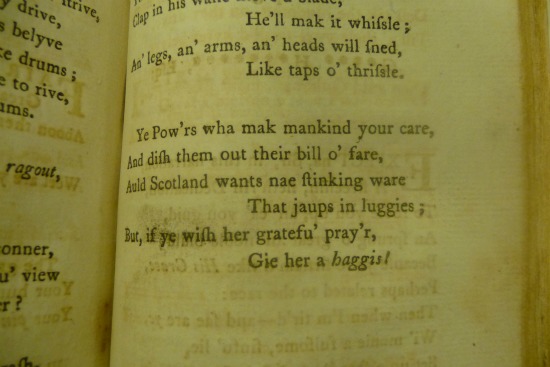

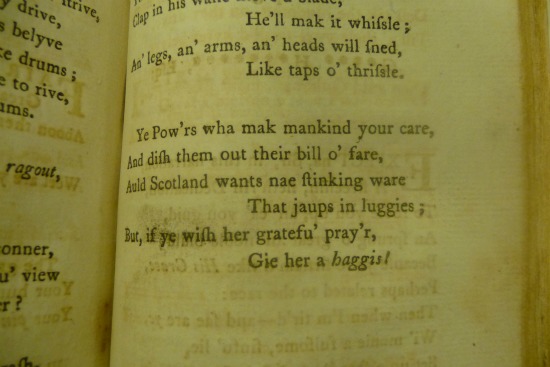

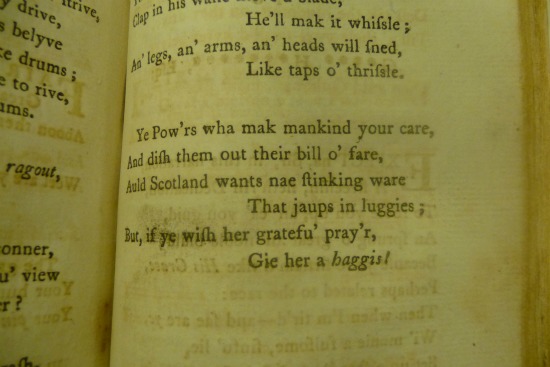

Ye pow’rs, wha mak mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill o’ fare,

Auld Scotland wants nae stinking [skinking] ware,

That jaups in luggies;

But if ye wish her gratfu’ prayer,

Gie her a Haggis!

Trans.:

You powers, who make mankind your care,

And dish them out their bill of fare,

Old Scotland wants no stinking {watery} ware,

That splashes in small wooden dishes;

But if you wish her grateful prayer,

Give her a Haggis!

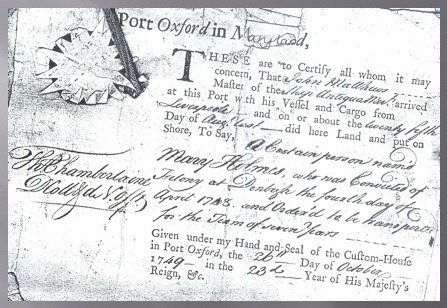

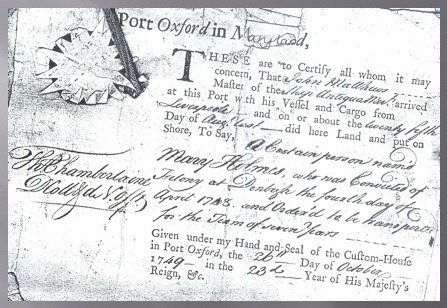

The Rubenstein’s copy of this so-called Stinking Edition was purchased by the Duke Library in 1951. It was first owned, however, by one of the original subscribers (or financial supporters) of the edition, a Mr. John Grant, who signed the title page.

Interestingly enough, a keyword search for “stinking” in the Rubenstein library holdings retrieves this book and only this book. No doubt this is a positive thing for our collections.