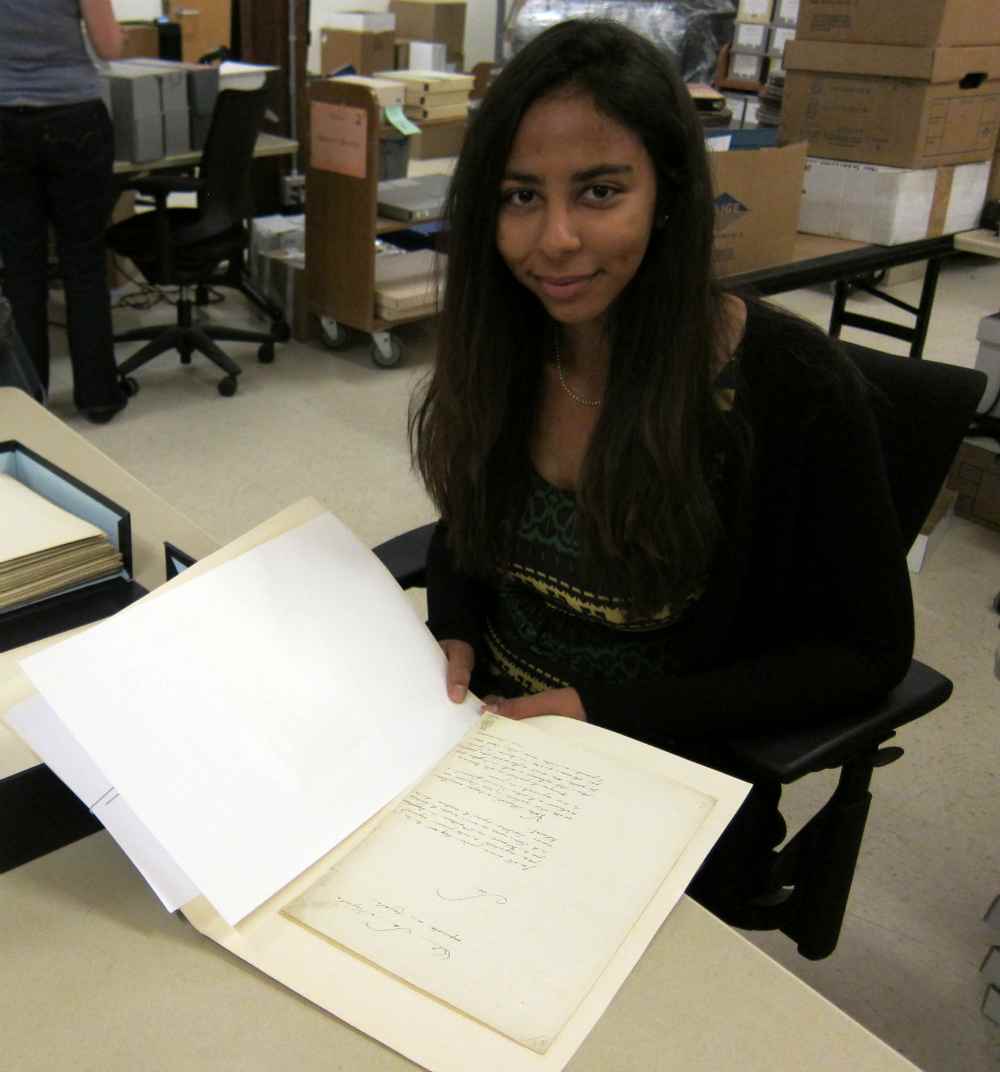

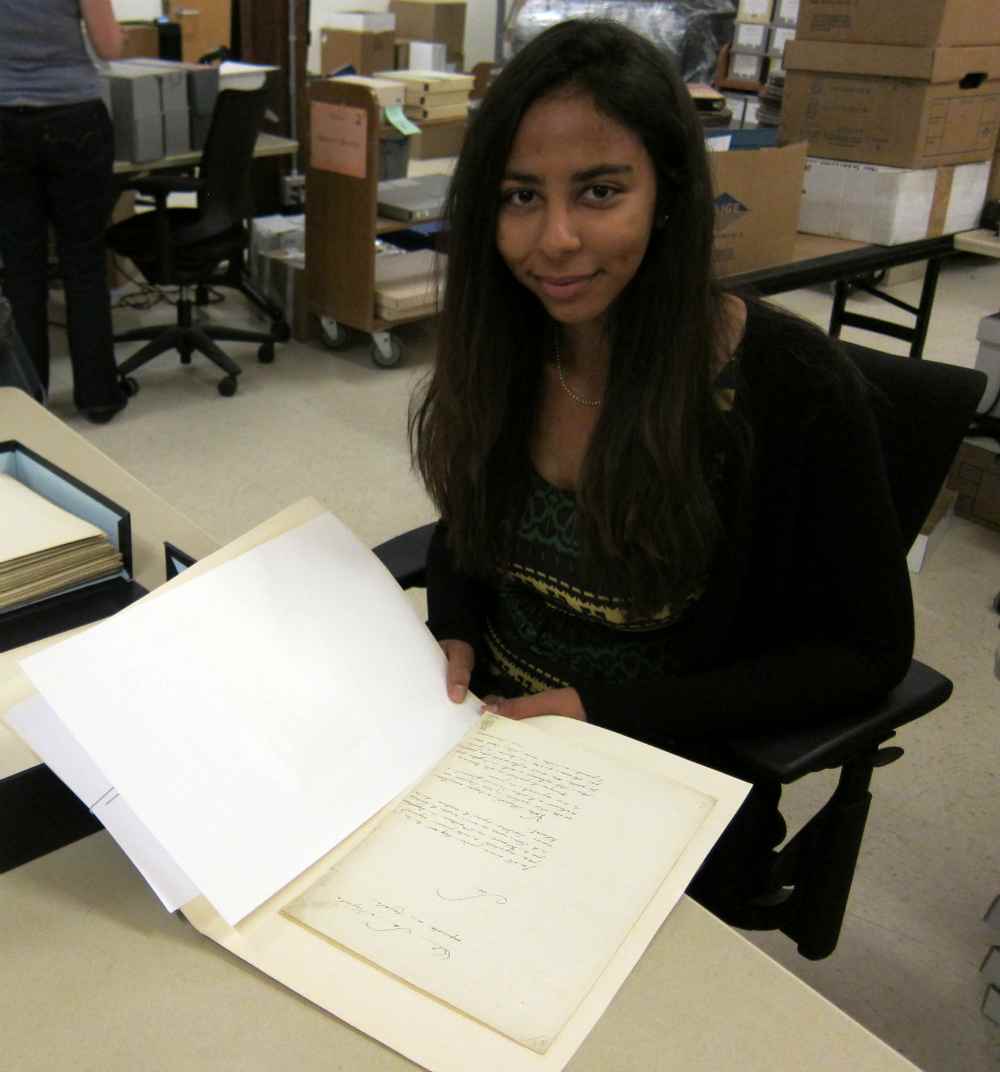

A few months ago, I processed the James Ludovic Lindsay Collection of French Manuscripts, which is by far the largest collection I have processed since I started working in Technical Services in October. As a freshman, I was incredibly excited to work on this collection. The collection is composed of 223 items, mostly letters and administrative papers, all dating to the French Revolutionary era (late 18th and early 19th century). Though the collection may not seem extremely appealing, unless you are an administrative papers-type person, it did have a few gems that are worth noting.

Let me begin with a little background on the collection. The collection was assembled by James Ludovic Lindsay, the 26th Earl of Crawford, and formed part of the larger “Bibliotheca Lindesiana,” a sizeable private library that Lindsay inherited from his father, Alexander, in the mid-1800s. Like his father, Lindsay had a passion for French Revolutionary writings. While Duke does not hold Lindsay’s entire collection (it was auctioned to many different entities), we have acquired a few items that are quite unique.

For example, scattered amongst mostly legal and administrative papers, I discovered a letter addressed to the Emperor Napoleon from a lawyer, Arnoud Joubert. The document was in perfect state, with no visible damage at all. I was most surprised by Joubert’s writing style (we also possess other letters from him). One would think that writing to an Emperor, especially once the monarchy had fallen, would require extreme politeness. However, Joubert did not make an extra effort towards Napoleon. This document, Box 3, Folder 160, made me wonder if there were other items of interest in the collection.

One such letter, from Cardinal Albani addressed to Alexander I, Emperor of Russia, requests the Emperor’s protection from French authorities. What is most interesting about this letter is that it is well-known that Alexander I and Napoleon had a tense relationship, and that Alexander often referred to Napoleon as “the oppressor of Europe and the disturber of the world’s peace.” This just shows that despite the fall of the monarchy, which hypothetically should have lessened tensions in France, and pleased most French citizens, certain individuals still searched for asylum in other foreign countries.

Another thing that I was not prepared for was how the documents were dated. Many of them used the old French Republican calendar. Unlike our Gregorian calendar, this calendar began with the fall of the French Republic in 1789, which was then renamed Year I. For a little over 12 years, this calendar replaced the commonly used Gregorian calendar in France.

Processing this collection definitely improved my knowledge of older French, and I am confident I can now read any sort of handwriting. Some of the pieces were near illegible, and it was sometimes difficult to decipher what was being said. But do not worry: if you ever have to write a paper on this period, or even if you are just curious about old French manuscripts, you should take a look at these documents.

Post contributed by Sophia Durand, Technical Services student assistant and Trinity ’15.

“One would think that writing to an Emperor, especially once the monarchy had fallen, would require extreme politeness. However, Joubert did not make an extra effort towards Napoleon”

Beaucoup d’étrangers (et même de Français) ont cette idée assez fausse des relations entre suzerain et subordonnés. Au Moyen-Âge, le roi était carrément tutoyé.

Plus tard, et même sous Louis XIV, les écrits, destinés à être vus par le roi seul, pouvaient être beaucoup plus directs que les paroles, toujours susceptibles d’être entendues par d’autres et, donc, en effet très formelles et polies. Voir par exemple certaines lettres de Le Nôtre (qui d’ailleurs écrivait un français plus qu’approximatif). En ces temps-là, le roi lui-même enjoignait entre autres à ses généraux d’être bref, concis et de ne pas s’embarrasser de fioritures.

Un peu paradoxalement, ce sont plutôt maintenant les Présidents, dont certains, même parfois en public, n’hésitait pas à utiliser un langage de charretier, qui peuvent se montrer d’une susceptibilité extrême quant aux formes selon lesquelles on s’adresse à eux.

Glad to see an article about the rich rare manuscripts’ collections at Perkins. I wish I had realized there was one specifically on the French revolutionary era and Napoleonic empire when I did research there, too bad. I hope this article would held people in the future from not doing the same mistake.

One remark concerning the end of the article “Another thing that I was not prepared for was how the documents were dated. Many of them used the old French Republican calendar. Unlike our Gregorian calendar, this calendar began with the fall of the French Republic in 1789, which was then renamed Year I. For a little over 12 years, this calendar replaced the commonly used Gregorian calendar in France.”

True, some deputies and public figures often referred to 1789 as Year I of Liberty. Still, this idea never became official and was progressively abandoned after the downfall of the Monarchy on August 10th 1792 and the consequent proclamation of the first French Republic on September 22nd.. The revolutionary calendar was definitely set around September 1793 after a commission led by Gilbert Romme presented its project of “republican calendar” to the National Convention -a project which had been called on by the new deputies after the September 1792 events -. From that moment, all official papers would have to consider Sept, 22 1792 as the first day of the revolutionary era or (sometimes called era of the French) with 1792 thus being year I, not 1789. The Gregorian calendar was restored on 1806 – year XIV.