On November 28, 1980, the Duvalier regime unleashed a campaign of violent repression on the independent press and human rights activists, destroying the Radio Haiti station on Rue du Quai in downtown Port-au-Prince. The crackdown was not unexpected: in October of that year, Jean-Claude Duvalier had decreed on the National Radio station that only state media would be permitted, that “the party is over” (“le bal est terminé”) for independent Haitian media. In response, Jean Dominique composed his prophetic (and beloved) editorial Bon appétit, messieurs, in which he sardonically declares, “gentlemen, journalists of the official press — the country is yours and yours alone from now on. And all will be beautiful, all will be peaceful, all will be idyllic, all will be pink and wonderful!” and warns these “official journalists” of what will befall Haiti when the independent press is silenced. Ronald Reagan’s triumph in the US presidential election that November meant decreased international pressure on Duvalier’s government – which was largely dependent on US aid – to respect human rights. And so, on November 28, the inevitable crackdown occurred. More than a dozen of Radio Haiti’s journalists were imprisoned, tortured, and expelled. The regime issued an order to kill Jean Dominique on sight; he escaped to the Venezuelan embassy and later went into exile with Michèle Montas in New York. In the years that followed, resistance to the regime spread throughout the country, as economic conditions worsened for the majority of Haitian citizens while the Duvalier family’s lifestyle grew more ostentatious, lavish and dissipated.

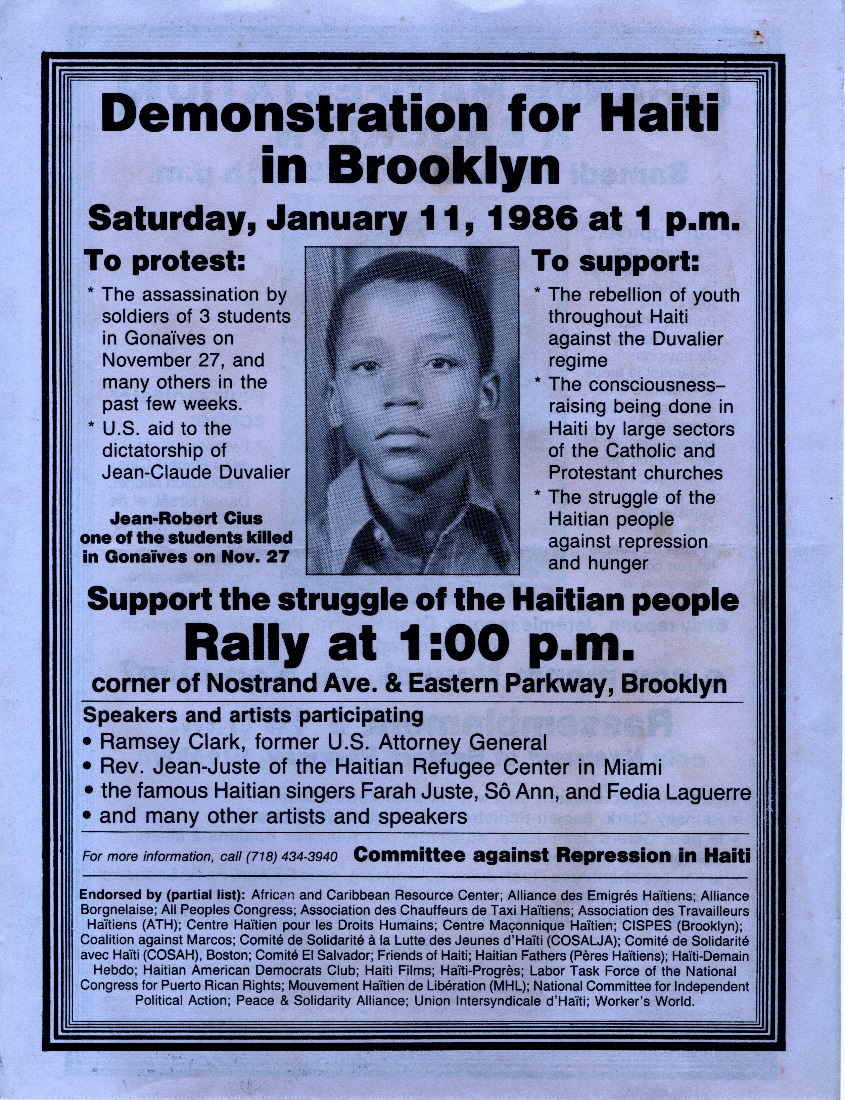

On November 28, 1985, five years to the day after the 1980 crackdown on the independent media, protests broke out in Haiti’s third-largest city, Gonaïves. Three high school students — Jean-Robert Cius, Mackenson Michel, and Daniel Israël – were gunned down by Duvalier’s forces. In photos, they are heartbreakingly young – boys, not yet men. The teenaged martyrs were christened the “Twa Flè Lespwa” (Three Flowers of Hope), and their deaths catalyzed outrage and resistance to the regime, both within Haiti and in Haitian communities abroad.

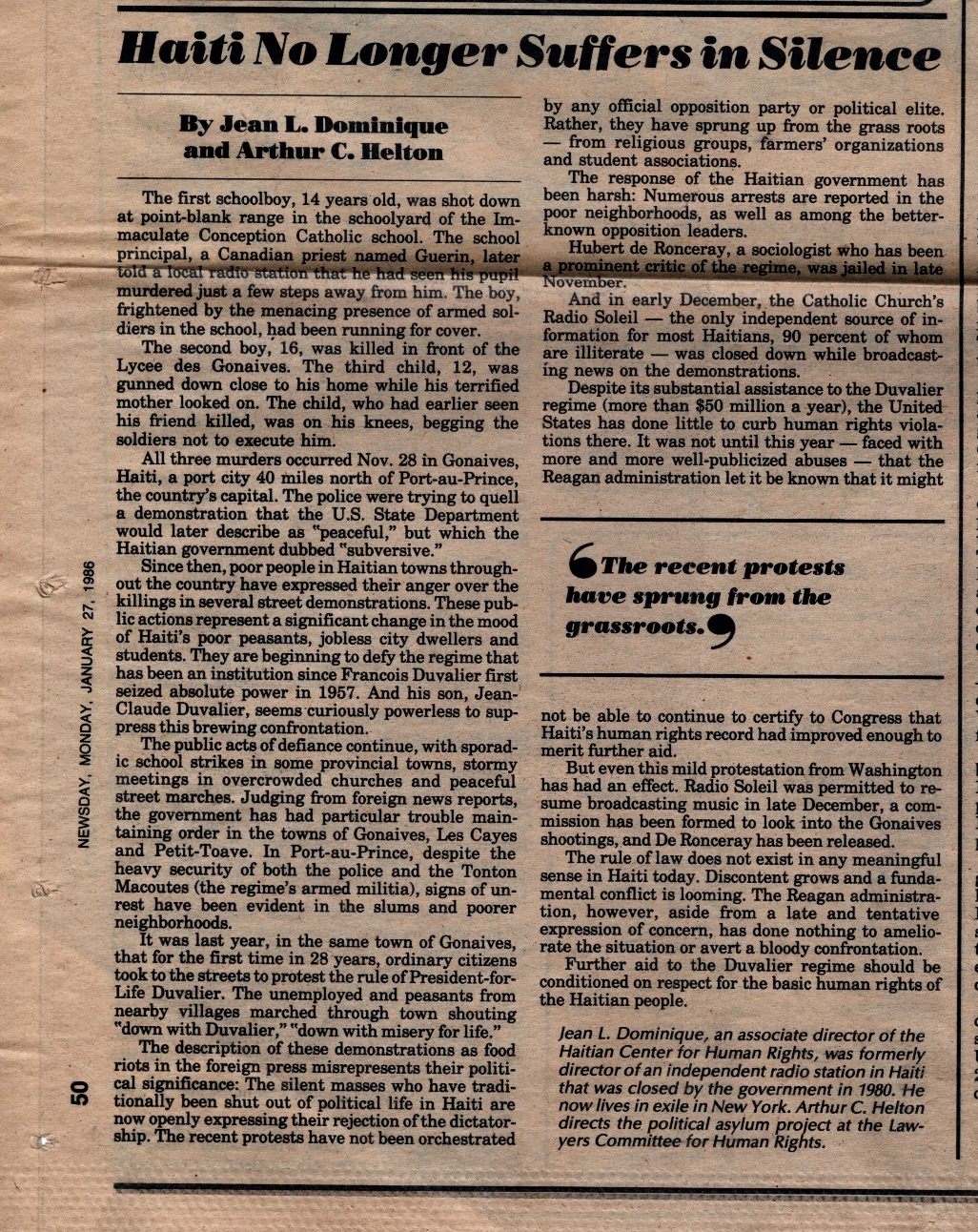

In January 1986, Jean Dominique co-authored a short op ed in Newsday with lawyer and human rights advocate Arthur Helton, discussing the deaths of the Twa Flè Lespwa, the grassroots agitation provoked by their murders, and the United States’ complicity in supporting the Duvalier regime.

They warn, perhaps cautiously: “Discontent grows and a fundamental conflict is looming.” The conflict was indeed looming, but it was not yet clear how imminent it might be.

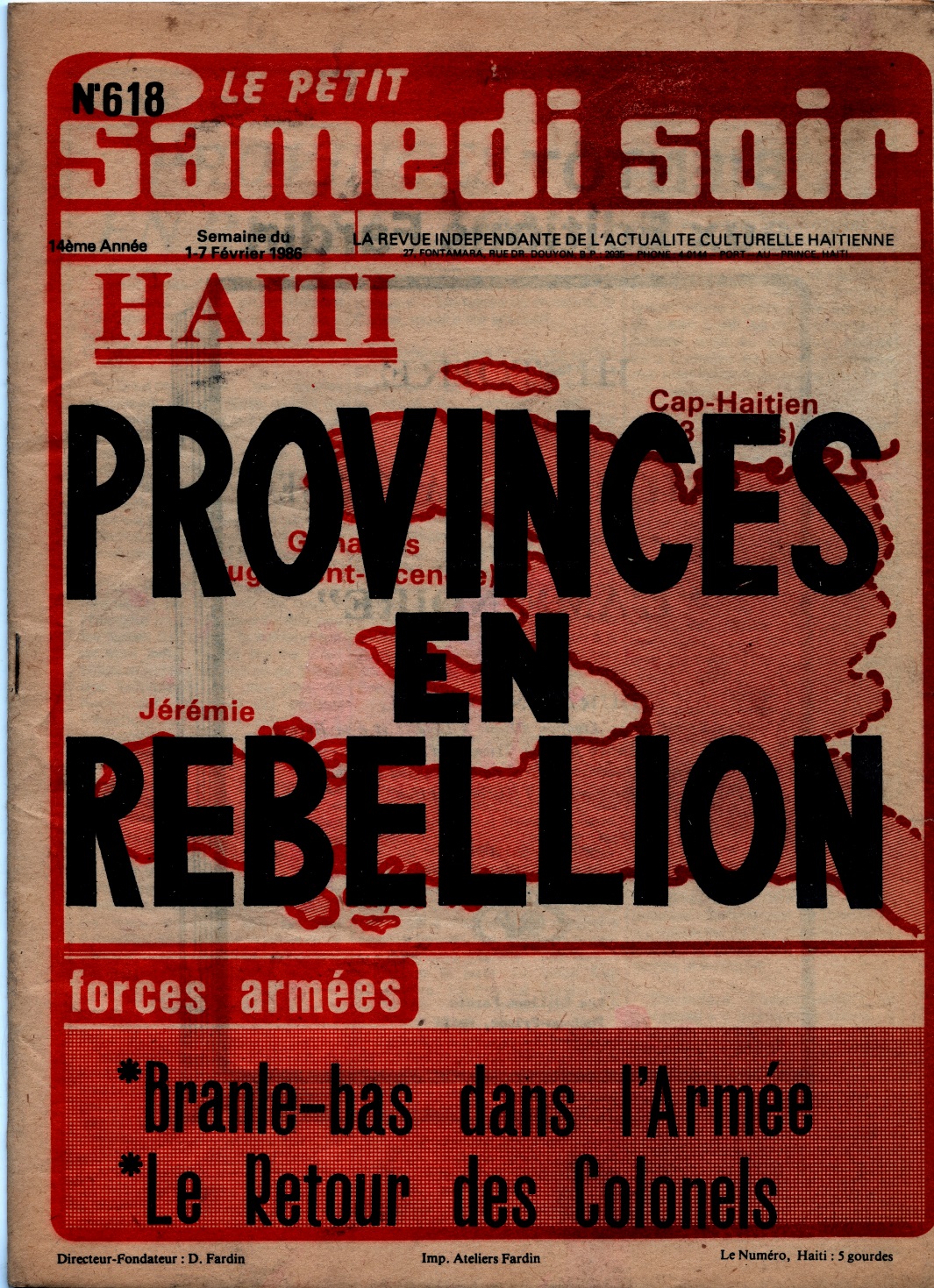

But on February 7, 1986, just over a week after Jean Dominique’s and Arthur Helton’s editorial was published, it happened: Jean-Claude Duvalier and his family boarded a US Air Force cargo plane and fled to France. On March 4, Jean Dominique and Michèle Montas returned to Port-au-Prince, where many thousands of people – “une masse en délire,” a delirious crowd, according to the Haitian newspaper Le Nouvelliste – received them at the airport and nearly carried them to the old Radio Haiti station on Rue du Quai.

The station had been ravaged, their equipment smashed. But the recordings, miraculously, had survived. J.J. Dominique – Jean’s eldest daughter, who became the station manager after 1986 — explains: “We always said, ‘The Macoutes, they may destroy, but they don’t know the true value of so many things’… They didn’t think, they didn’t understand that the most valuable thing at the station was the work contained in the station’s archive.”

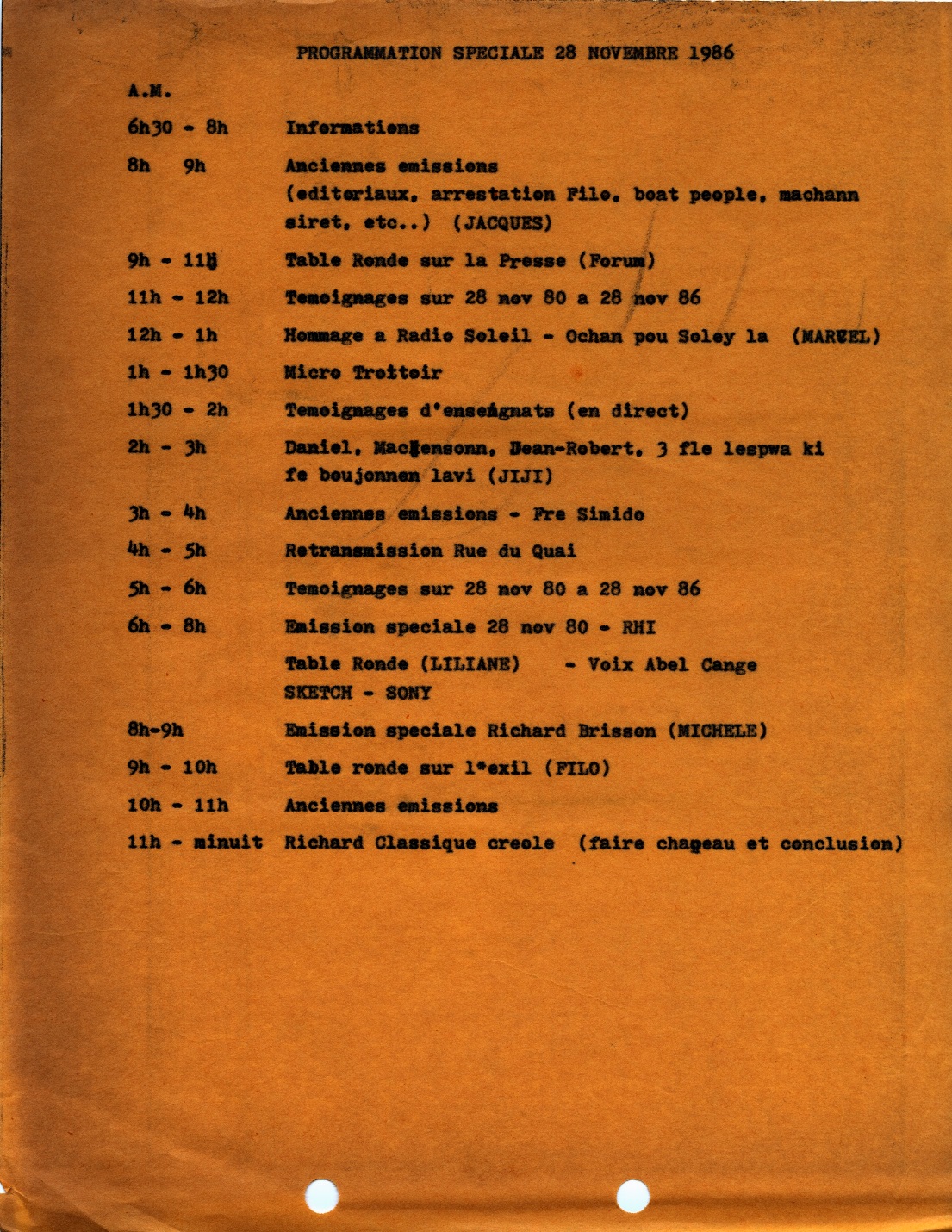

With assistance from the Haitian people – many of whom, though very poor, gave what little money they could afford — the station reopened in 1986. On November 28 of that year, Radio Haiti held a day-long commemoration of November 28, 1980 and November 28, 1985. It included tributes to the Twa Flè Lespwa and to station manager Richard Brisson who had been killed in 1982.

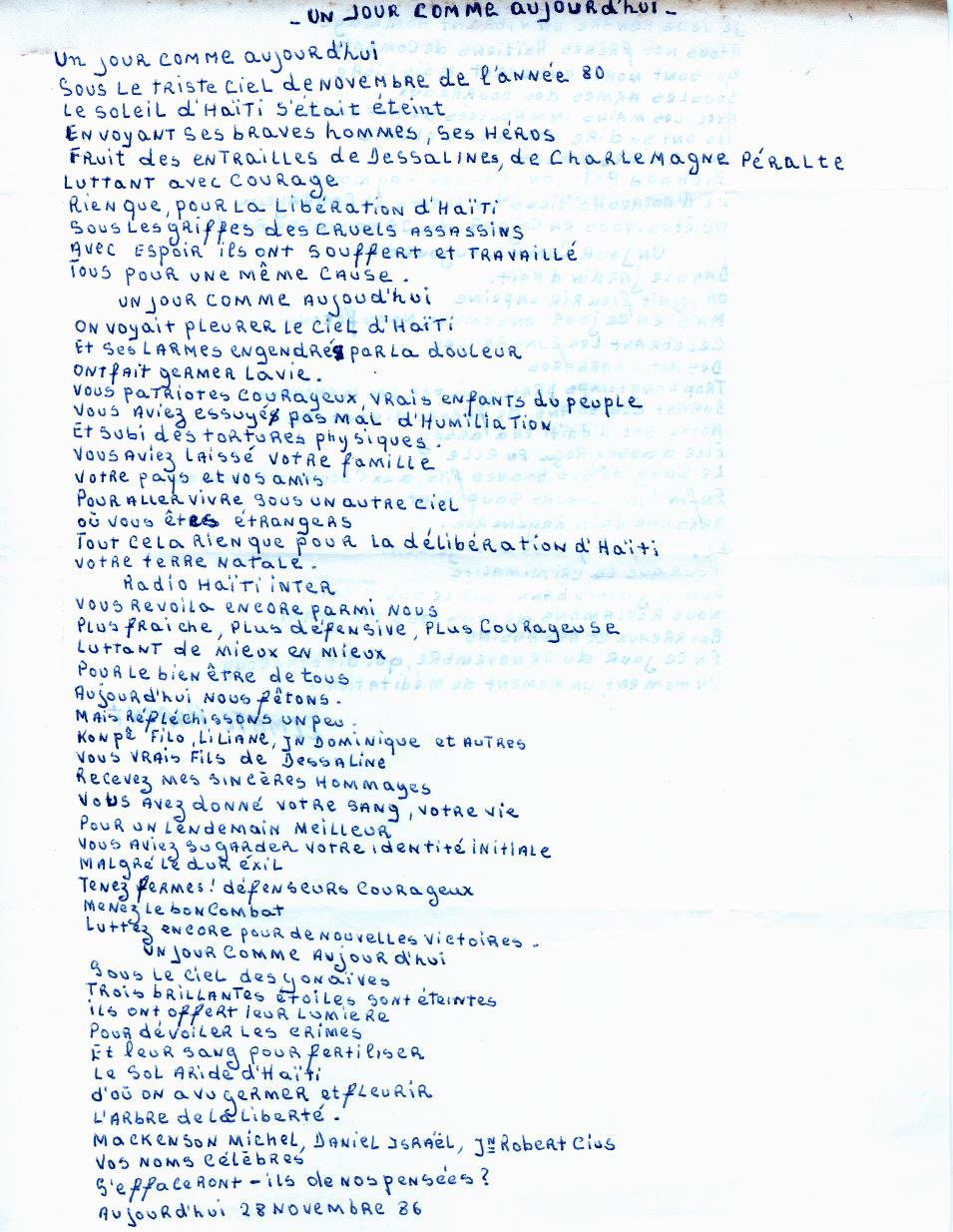

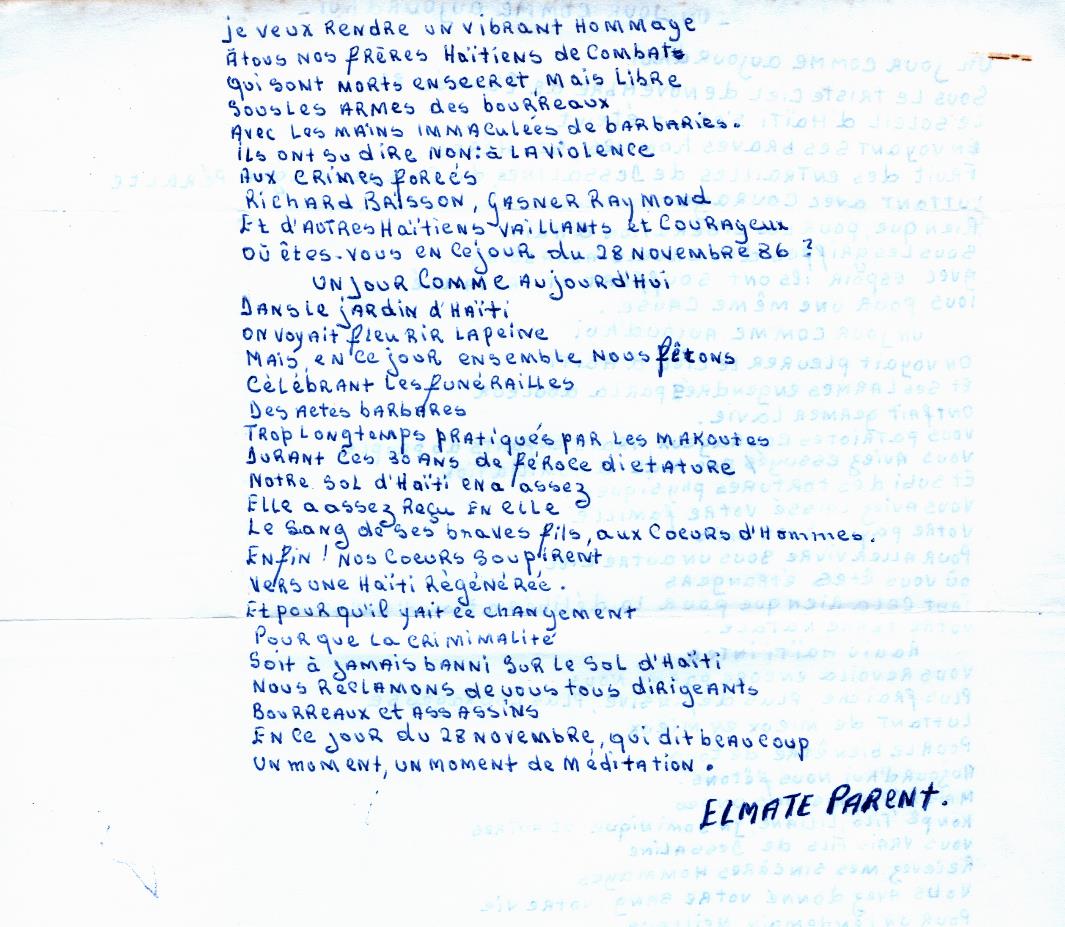

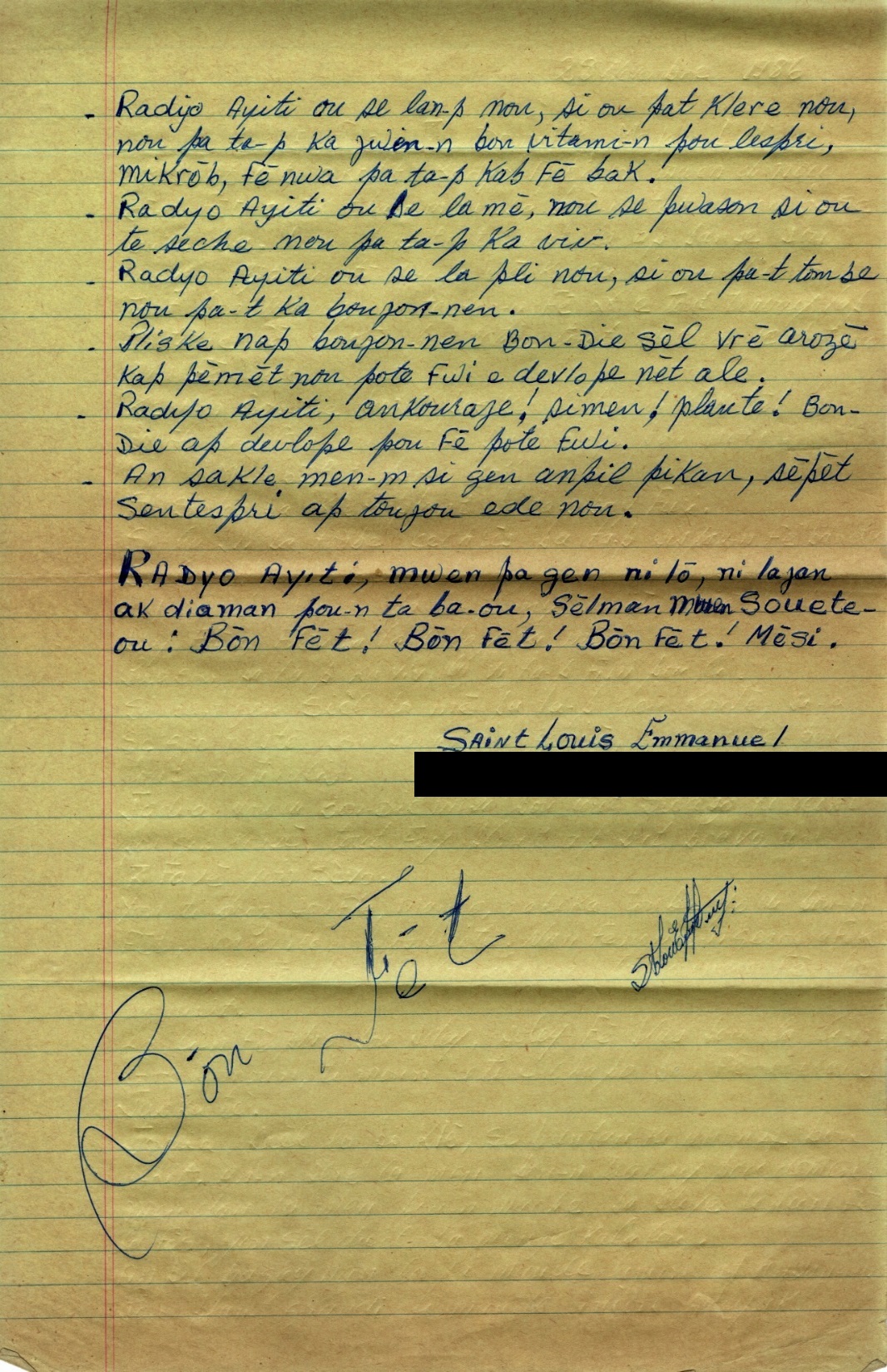

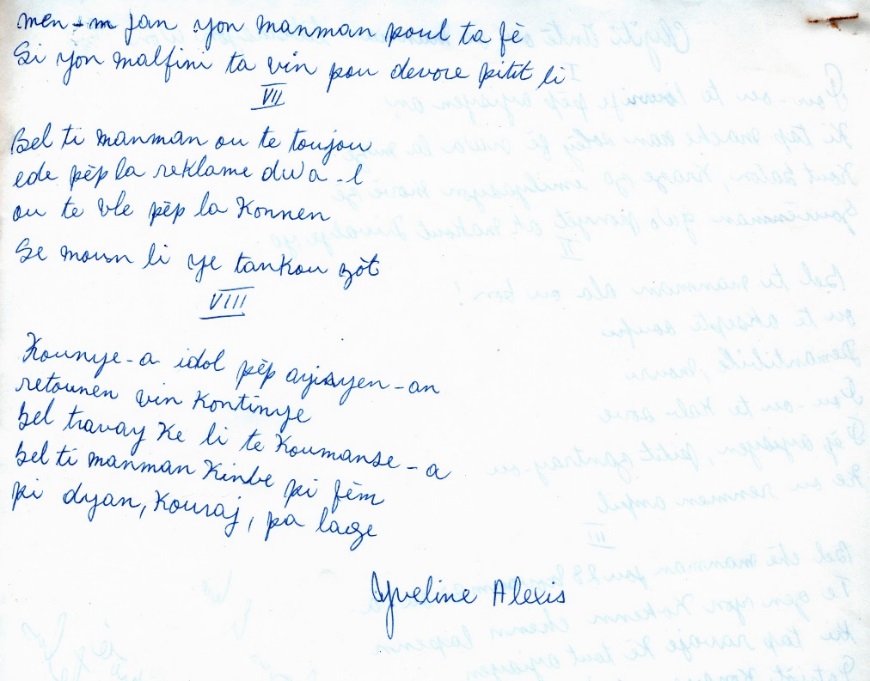

The archive also contains many pages of poetry written by Radio Haiti’s listeners, in Haitian Creole and French, on the Twa Flè Lespwa, the reopening of the station and the return of the journalists. The heartfelt, earnest intensity of these poems (these love letters, really) evinces the public’s devotion to Radio Haiti. For Radio Haiti’s listeners, the station was more than a station; it was a symbol of liberty, grassroots democracy, and freedom of expression. For Radio Haiti’s listeners, the journalists were more than journalists; they were heirs to the revolutionary legacy of Haitian heroes who had fought against French colonizers and US occupiers. For me, as the project archivist, finding these poems is a reminder of how irreplaceable and beloved Radio Haiti was and still remains, and how important this archive is.

A day like today

Under the sorrowful sky of November 28 in the year ‘80

Haiti’s sun went out

Sending these brave men, these heroes,

Fruit of the body of Dessalines, of Charlemagne Péralte

Fighting with courage,

For nothing more than the liberation of Haiti,

Upon the claws of assassins cruel

With hope they suffered and toiled

All for the same cause.

A day like today

The skies of Haiti wept,

And her tears, borne of pain,

Allowed life to germinate.

You, brave patriots, true offspring of the people,

You have suffered such humiliation

And endured physical torture.

You left your families

Your country and your friends

To go and live under another sky

Where you were strangers

All of this for nothing more than the deliberation of Haiti

Your native land…

A day like today

In the heavens over Gonaïves,

Three brilliant stars burned out

They gave their light

To reveal crimes

And their blood to fertilize

The arid soil of Haiti

Whereupon shall sprout and grow

The tree of freedom.

Mackenson Michel, Daniel Israël, Jean Robert Cius

Will your famous names,

Be erased from our thoughts?

Today, 28 November ’86…

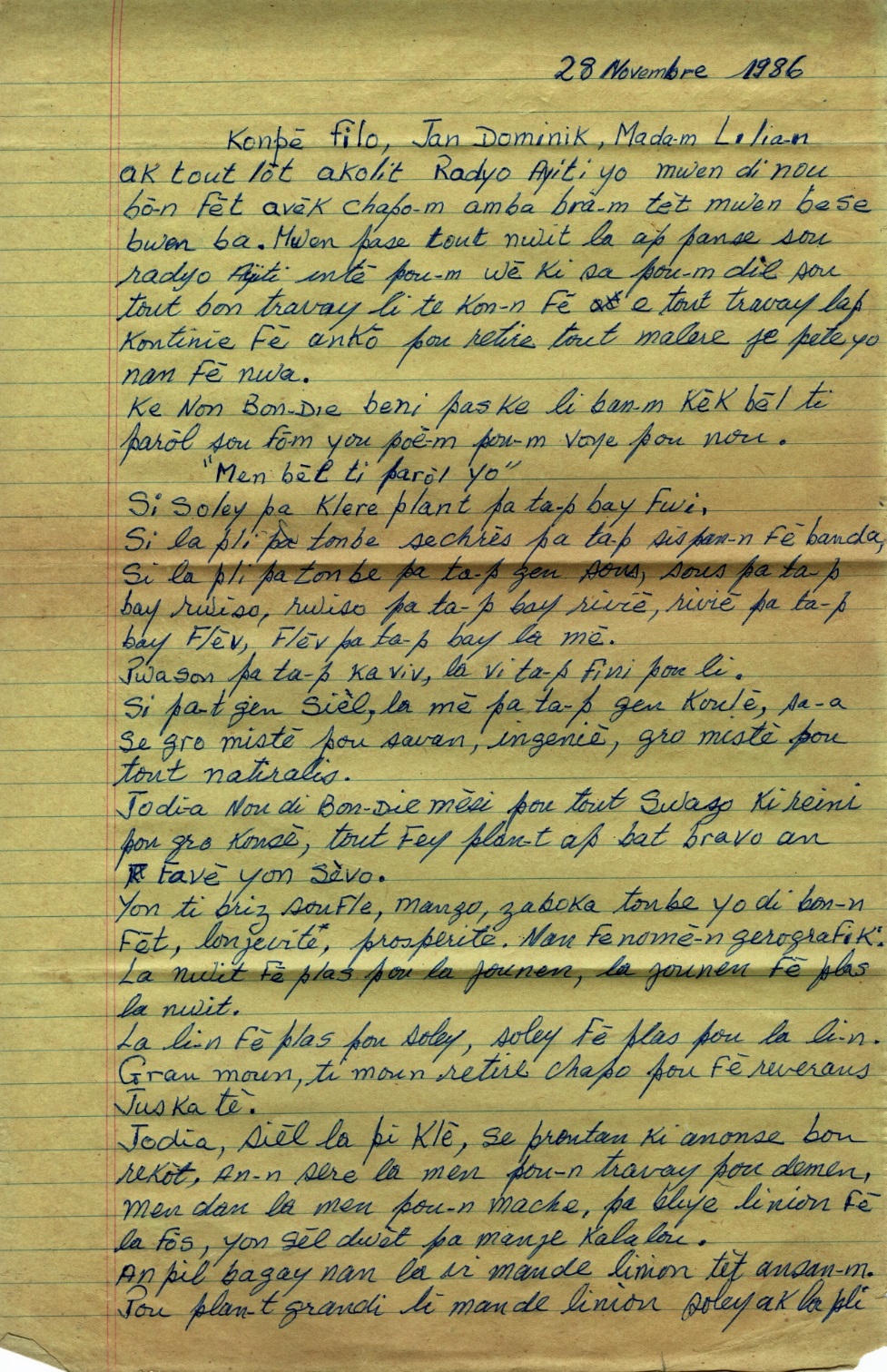

“Men bèl ti paròl yo” (“Some lovely little words”) draws on metaphors of nature and harvest befitting Jean Dominique, a man who was, after all, an agronomist before he was a journalist and activist. The poet touchingly explains that he “spent all night thinking about Radio Haïti-Inter” before setting pen to paper.

If the sun didn’t shine, plants would not give fruit

If the rain didn’t fall, drought would never stop dancing,

If the rain didn’t fall, there would be no springs

Springs would not give rise to rivulets

Rivulets would not become streams

Streams would not become rivers,

Rivers would not become the sea…

Radio Haiti, you are the sea, we are the fish

If you were to dry up, we could not live.

Radio Haiti, you are our rain,

If you didn’t fall, we could not bloom…

Radio Haiti, be encouraged! Sow! Plant!

God will bring it to fruition.

Let us weed, even if the thorns are many,

The pruning shears of the Holy Spirit will aid us always.

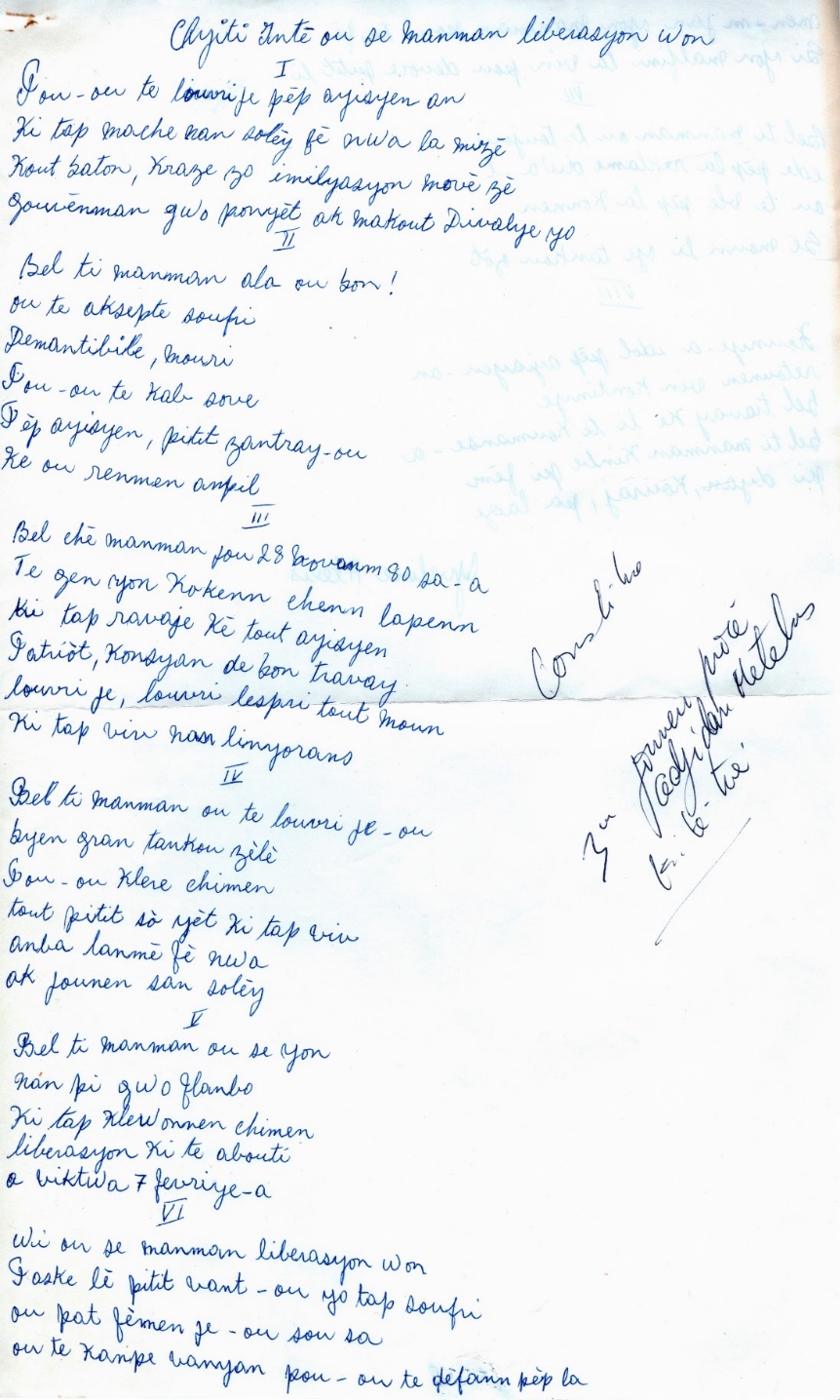

From “Haiti-Inter, You are the Mother of Liberation”:

Yes, you are the mother of liberation

Because when the children of your womb were suffering

You never closed your eyes to it

You stood bravely to defend the people

Just as a mother hen would do

If a vulture came to devour her children…

Now the idol of the Haitian people

Has returned to continue

The wonderful work it began

Beautiful mama, hold on tighter

Stronger – courage — never give up.

Post contributed by Laura Wagner, PhD, Radio Haiti Project Archivist.

The Voices of Change project was made possible through a generous grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities.