By Mary Yordy, Senior Conservation Technician

At the beginning of the quarantine, practical arrangements to retain connectivity to my desktop at work and forge other forms of digital connectivity with my workplace kept me busy. I researched questions about surface contamination of books and paper, I cleared out and organized files and reviewed hundreds of informative links and tutorials I’d neglected to study in my usual routine, wherein I’m juggling the day-to-day demands of my bench work against the influx of digital resources. But weeks became months, and I am used to seeing the results of a day’s work mounting up in the book press or filling shelves. Though I was diligent in my hours at home, after around six weeks I needed to produce something tangible, and I wanted it to be relevant to the life of the lab.

Work runs along a fulcrum from past to future that is understood collectively and concretely. Without that, it’s hard not to suspect we have become shadow boxers. How do we create assets for a post-epidemic future we cannot fully know? How do we make decisions about value and use without knowing what the future holds or when it will start? Luckily for me, the perfect project appeared under my fingertips late one night, going through my files at home: “Sewing Samples–2006.” Preserved within it were the beginnings of a project that related to the early history of the lab, one had the potential to provide knowledge to future workers in our craft.

The file held a collection of cards made during one of the early in-house workshops Beth Doyle taught for the three technicians on staff at the time: me, Rachel Ingold, and Diane Sutton. Beth taught us basic and more complex sewing methods, stitches and knots used in bookbinding. Recalling that day, sitting around an old library table in the 2006 lab, threw the impressive developmental span of Duke Library Conservation in sharp relief.

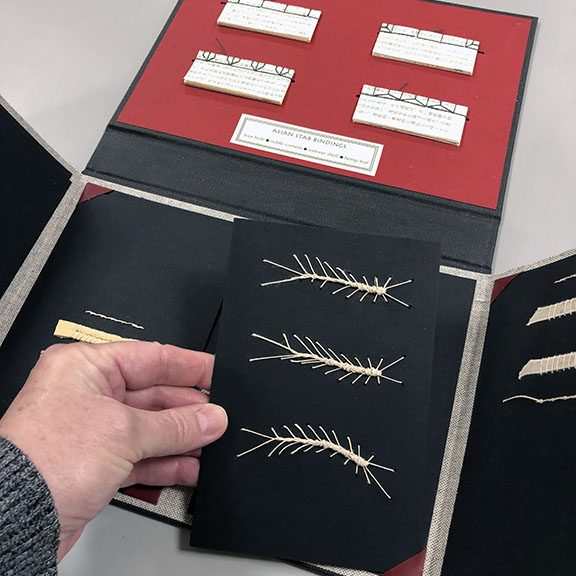

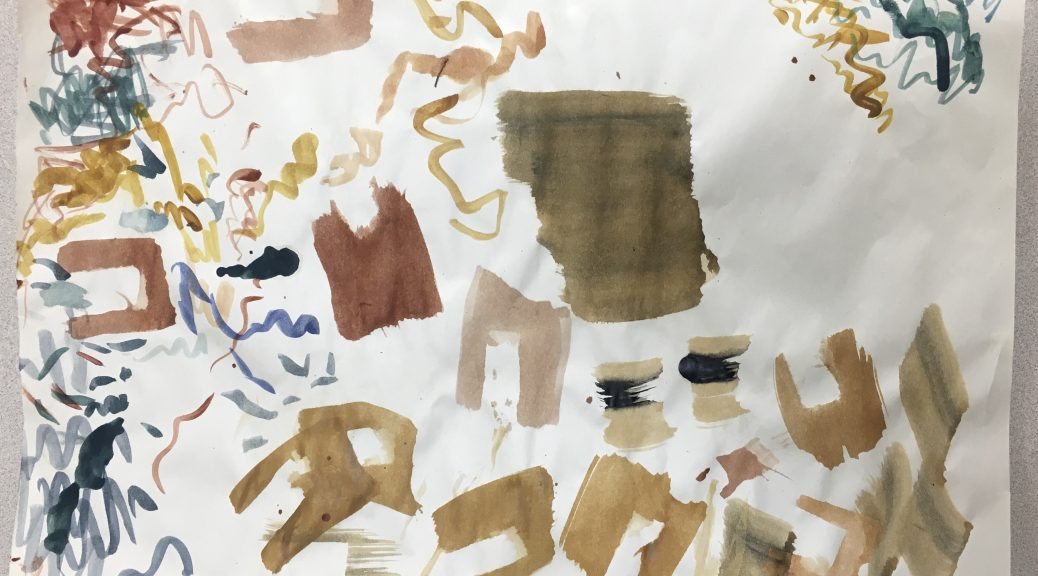

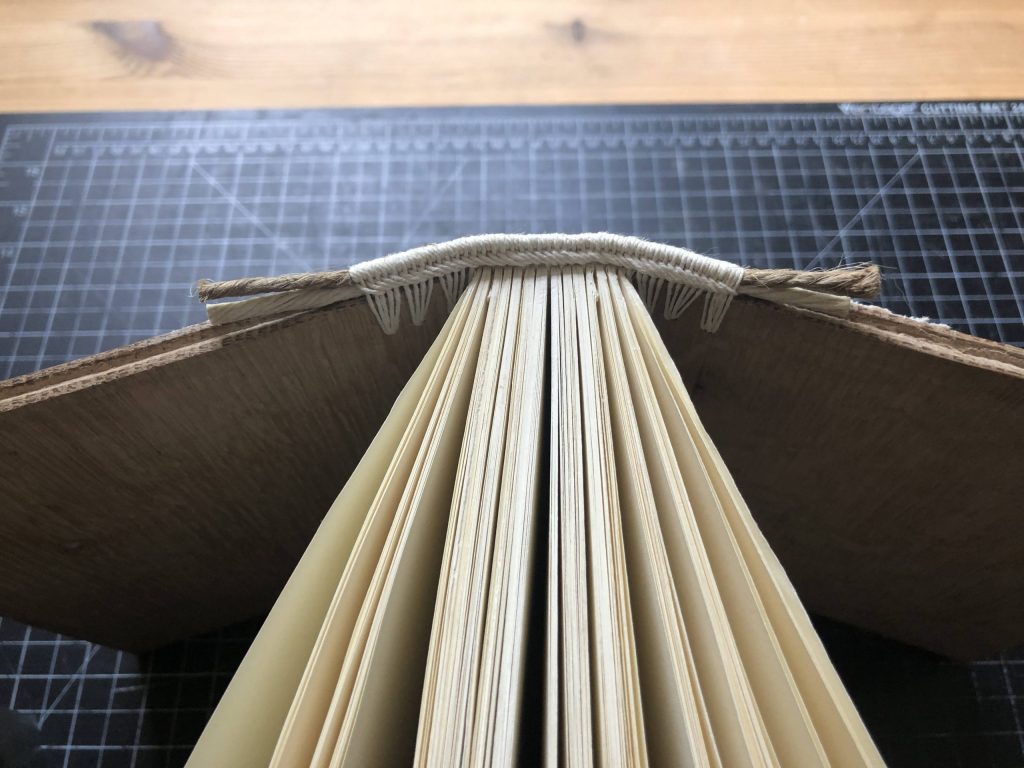

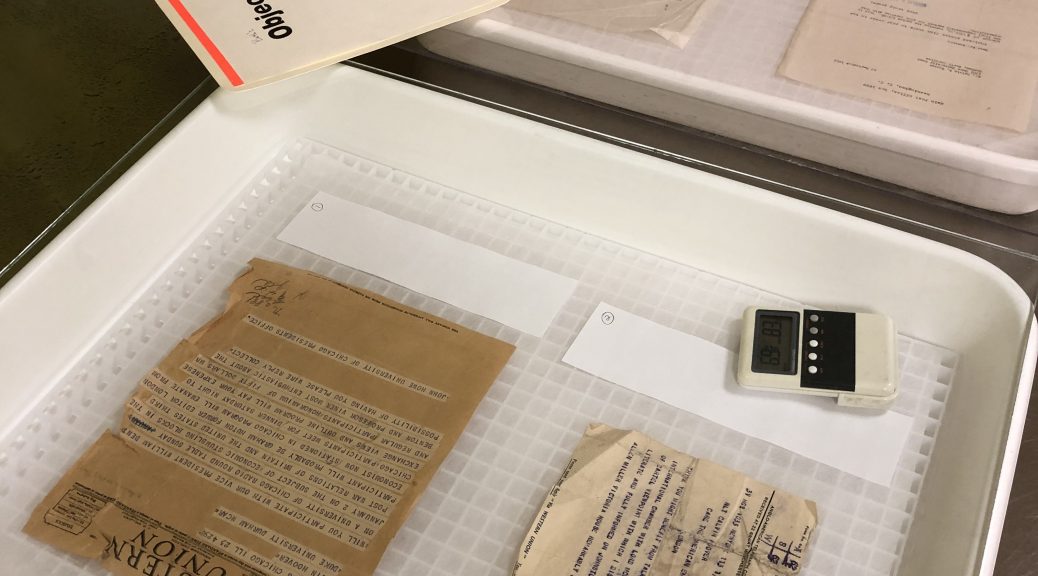

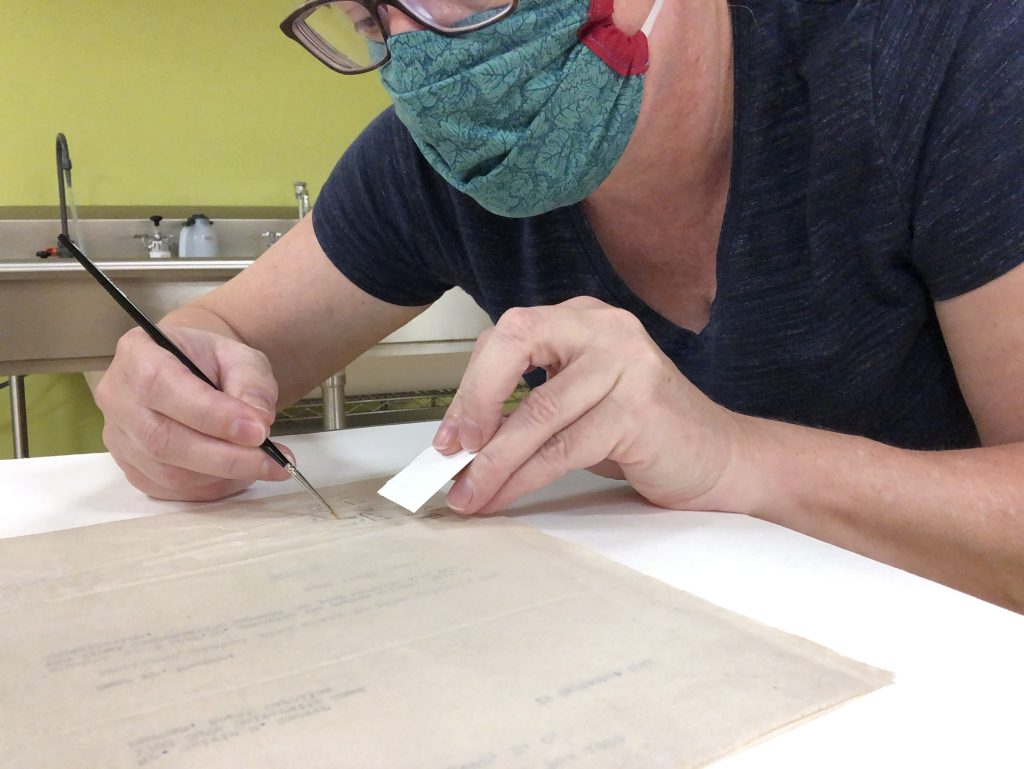

In addition to the samples sewn that day on index cards, there was a nearly complete set of the stitches sewn onto black paper folia in the folder. I had never completed this more advanced solo project based on Beth’s original workshop. The idea was to make something visually appealing, complete, and inclusive of additional visual information to orient a beginner to the application of the stitch in 3-dimensional structures.

Stitch sample cards made in the course of workshops work well as memory prompts for people who have already learned them. However, for beginners, the flattening of the sewing process onto a card and the need to infer structural information can make them a little baffling. I had come across this file once or twice before and verified that it was a worthy goal. But mid-quarantine, the project felt like more than that: it was like an arc from the beginnings of the lab, through this time of mass uncertainty, to the future gaze of someone beginning to learn bookbinding.

I finished sewing all of the samples on the face of black folia, located other visual information needed to design inserts for each folio, and built a gate-format accordion album in a hard case to hold them all. There are 8 spaces on the back of the fold outs so additional samples can be added–there are always more stitches to learn.