Keeping a large circulating collection in usable shape means you are often so busy fixing or boxing books to get them back on the shelf that you don’t have time to look at the contents. When a first edition of Mary Van Kleeck’s Women in the Bookbinding Trade came into the lab, however, we all stopped to take a look.

This book, originally published in 1913, is a fascinating look into the working conditions for women in the binding trade around the turn of the century. Margaret Olivia Sage had used the considerable wealth amassed by her late husband to form the Russell Sage Foundation in 1907 for “the improvement of social and living conditions in the United States”, specifically by using scientific research to advocate for progressive reforms. The foundation funded a series of studies which documented the condition of women’s work in important trades in New York City. The 1900 US census reported that over a quarter of women bindery workers were employed in the city, so the location offered a sizable sample to extrapolate conditions across the United States.

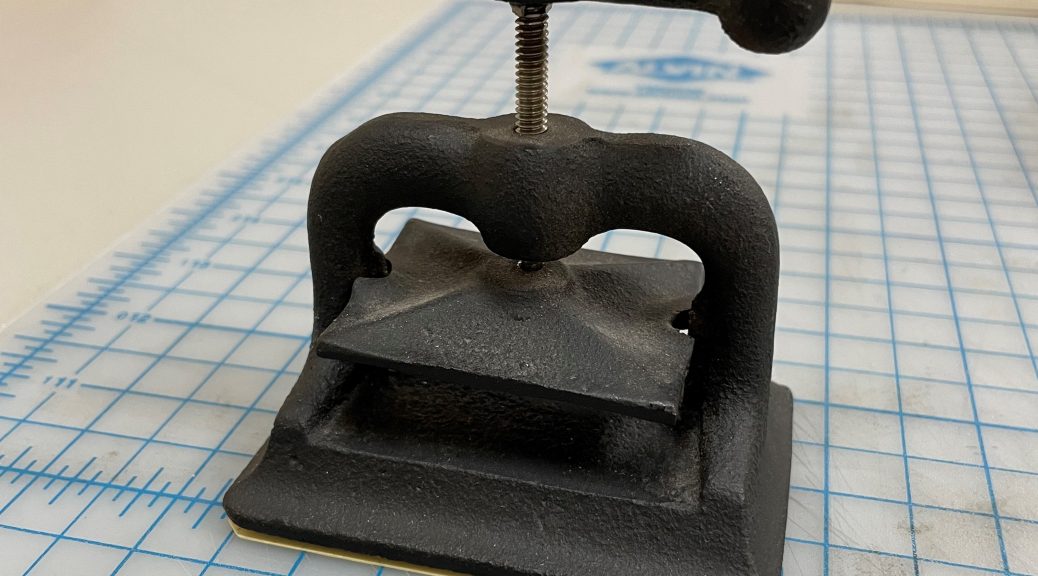

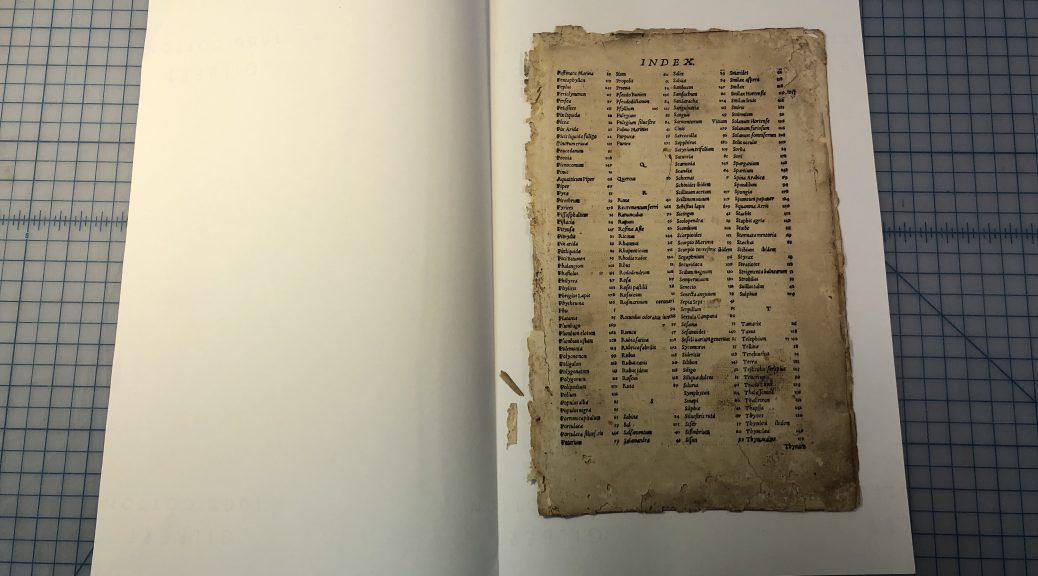

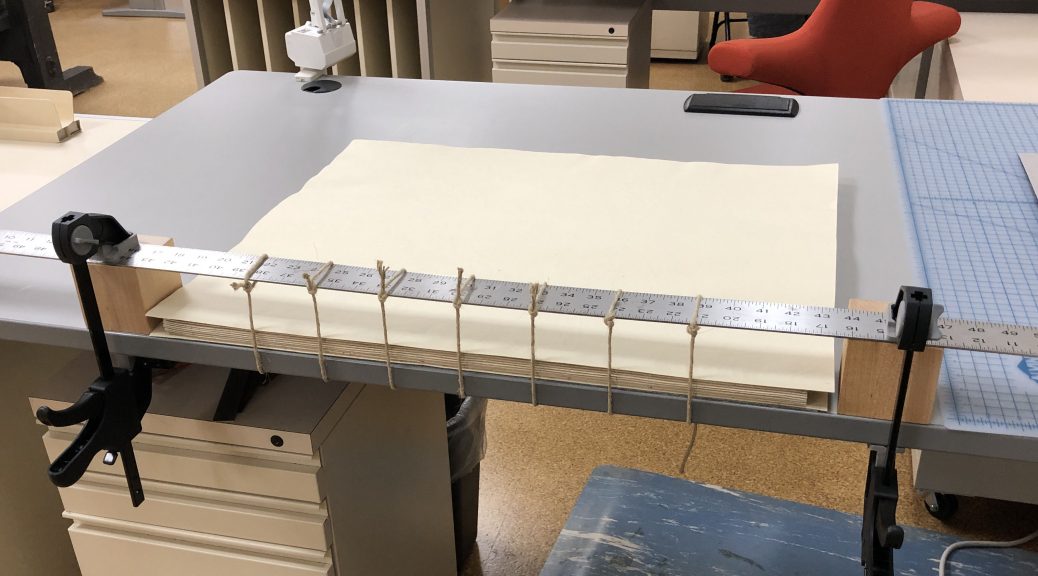

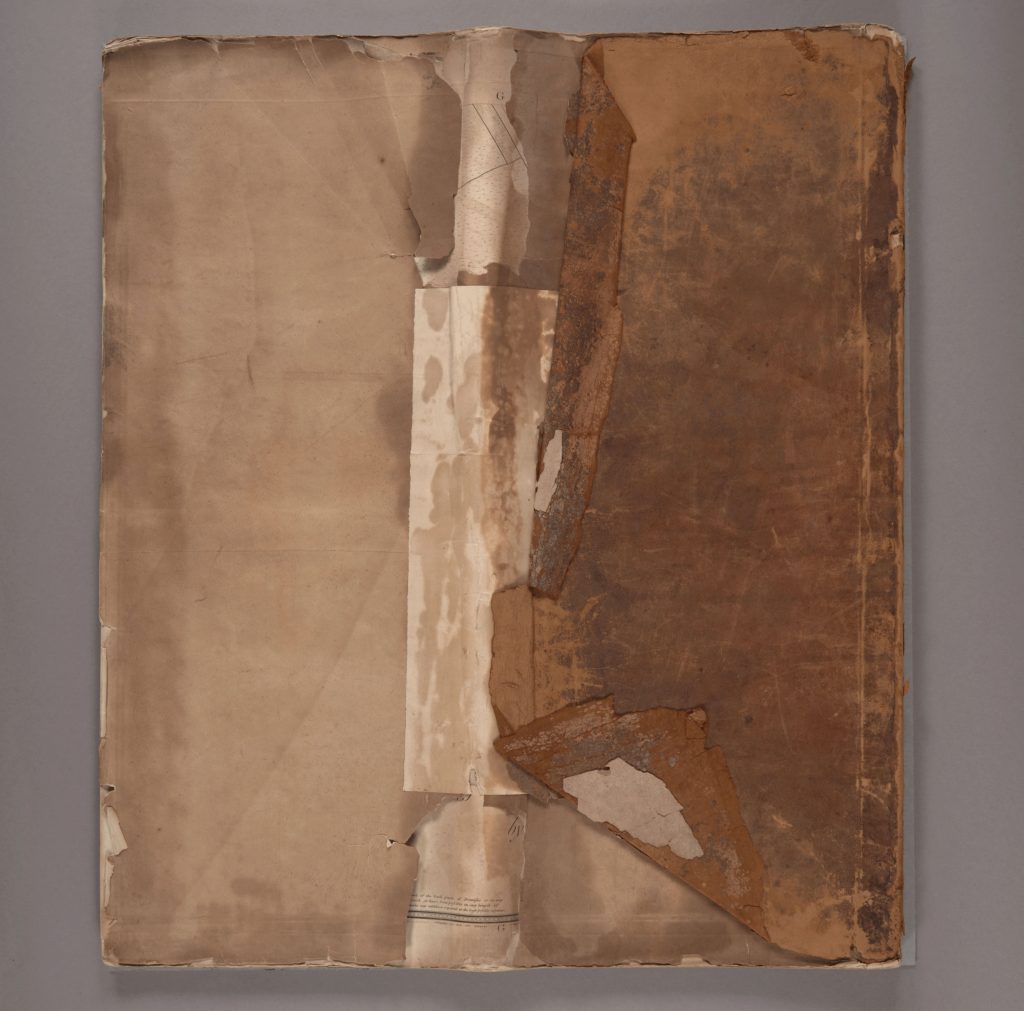

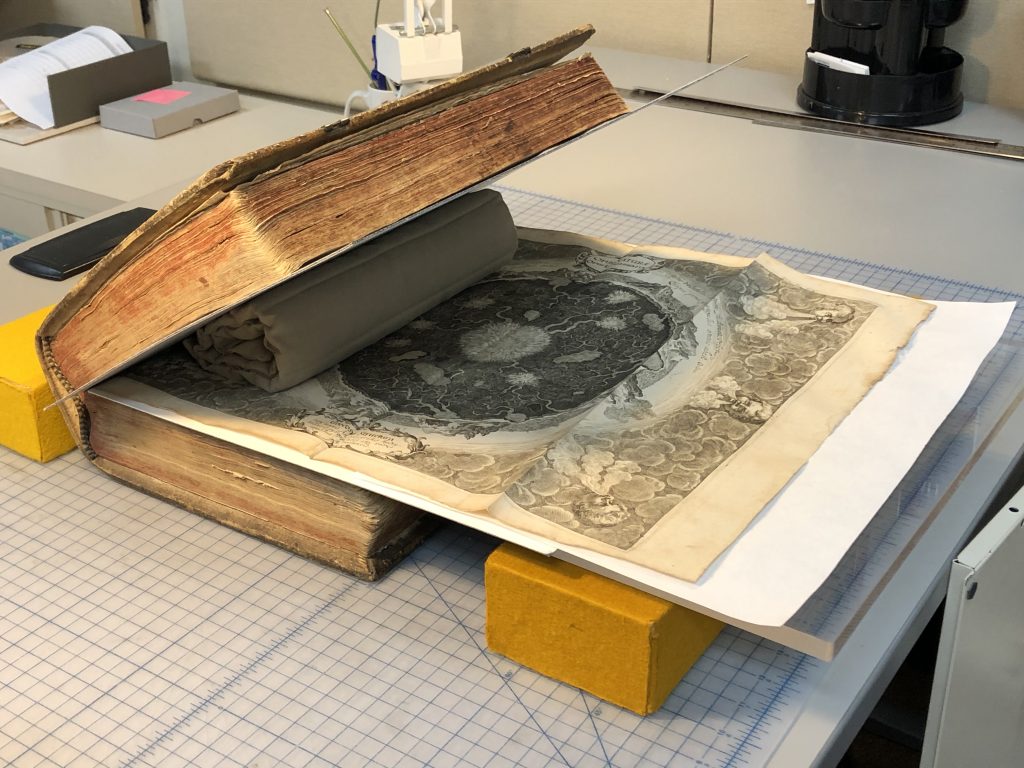

The turn of the century was an important period of transition for the binding trade. Work that was traditionally done completely by hand had become more mechanized in the late 19th century, and the number of women working in the trade was growing rapidly. Binderies were typically gender-segregated, with women relegated to less skilled and lower wage work, like folding, gathering, and sewing textblocks and endbands. In most cases, all of the forwarding, covering, and finishing work was done by men. Van Kleeck’s book includes a lot of photographs, which offer a look at the conditions of the workspaces, the roles assigned to each gender, and the shift from fully manual to machine-assisted labor during this time.

Van Kleek notes that the introduction of more capable binding machines displaced a lot of workers in the book trade, shifting them to lower wage work or out of a job entirely. The author describes the case of one woman who learned to operate a folding machine, allowing her to double her weekly wages to $9.00. Within a few years a newer machine arrived that made multiple machine operators obsolete. She was transferred to hand folding, which was harder physical labor and only paid 4 cents per 100 sheets. Working as quickly as possible she could only earn $7.00 per week (p. 51).

Van Kleek notes that the introduction of more capable binding machines displaced a lot of workers in the book trade, shifting them to lower wage work or out of a job entirely. The author describes the case of one woman who learned to operate a folding machine, allowing her to double her weekly wages to $9.00. Within a few years a newer machine arrived that made multiple machine operators obsolete. She was transferred to hand folding, which was harder physical labor and only paid 4 cents per 100 sheets. Working as quickly as possible she could only earn $7.00 per week (p. 51).

As a side note, this page caught my eye when I realized that the heads of the people in the bottom photo had just been drawn in. I’m not entirely sure why – maybe they were a bit blurry because the camera exposure was long and they were moving quickly? Was it to anonymize the workers, or to make them look more the part?

It is so interesting to see photographs some of these machines in action. The technology was advancing pretty rapidly in this period and most of these models no longer exist. Some versions can be seen at the American Bookbinders Museum in San Francisco.

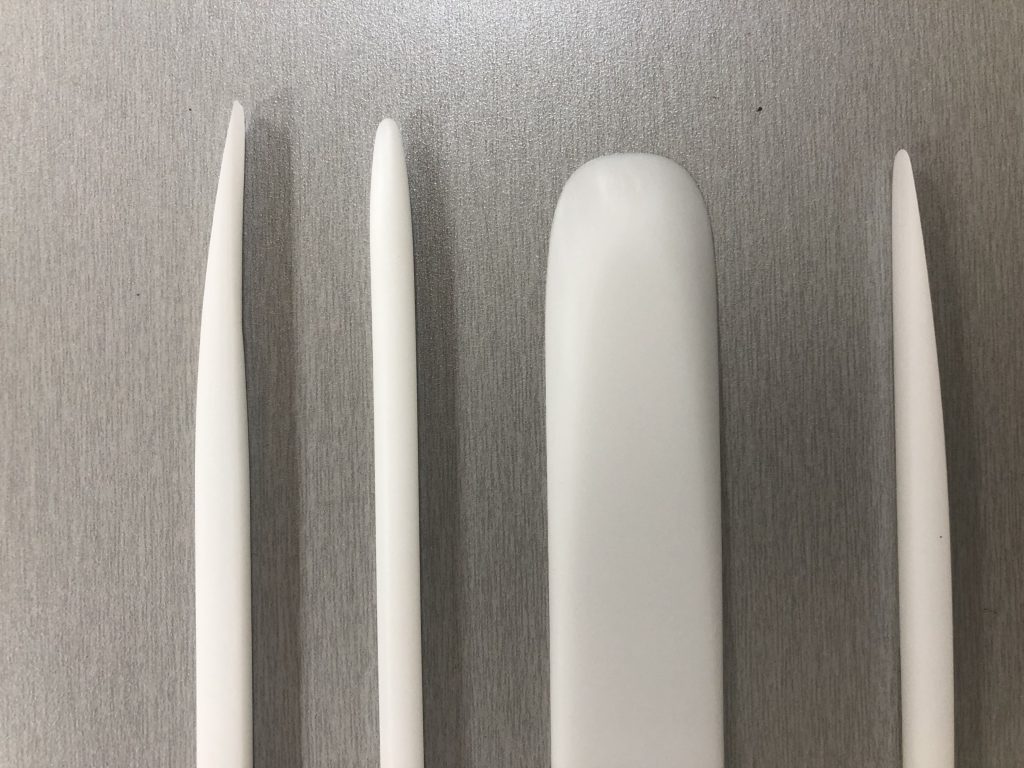

In the finishing department, women were often only found laying gold leaf onto covers, rather than operating stamping machines or gilding the edges of textblocks.

In the finishing department, women were often only found laying gold leaf onto covers, rather than operating stamping machines or gilding the edges of textblocks.

The introduction of electric lights in the late 19th century allowed businesses to operate at all hours. Without labor protections (and a supreme court actively hostile to organized labor), many factory workers were forced to work long hours. Van Kleek notes that binderies are legally classified as factories, and despite state laws barring any woman over the age of 16 from working more than 60 hours, workers regularly reported 14 hour shifts, 6 days a week. The book describes workers commuting to and from dangerous neighborhoods in the early hours of the morning. As a result, young women regularly went missing. The study also records rampant child labor violations in the book trade.

By examining the details of Mary Van Kleek‘s work, one can follow a line directly from this book to the establishment of the modern work week and labor protections we enjoy today. Van Kleek began working for the Sage Foundation shortly after its founding as the secretary of the Committee on Women’s Work. There she was mentored and trained by prominent labor activists like Florence Kelley and Lilian Brandt. Her research for this publication and others like Artificial Flower Makers (1913) and Wages in the Millinery Trade (1914) was instrumental in the passage of New York state labor laws limiting working hours in 1910 and 1915. During WWI, Van Kleek was appointed by Woodrow Wilson to lead the new Women in Industry Service group in the Department of Labor. That group published a report that became the basis for the Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, which established the eight-hour workday, five-day workweek, a federal minimum wage, overtime pay, and prohibited child labor.