or how a Scholarly Communications Officer Encourages Intellectual Inquiry and Upholds the Law

Kevin Smith

In my many years as an academic librarian, one of the things I have liked best is library patrons’ appreciation for librarians and the work that we do. So, when I became a lawyer as well, I was surprised by the realization that I would be spending a lot more of my time dealing with angry or unhappy people. Nevertheless, the work I now do at Duke is exactly what I hoped to find after law school, and it has been tremendously rewarding, even though I am sometimes the bearer of bad news.

In my many years as an academic librarian, one of the things I have liked best is library patrons’ appreciation for librarians and the work that we do. So, when I became a lawyer as well, I was surprised by the realization that I would be spending a lot more of my time dealing with angry or unhappy people. Nevertheless, the work I now do at Duke is exactly what I hoped to find after law school, and it has been tremendously rewarding, even though I am sometimes the bearer of bad news.

I became Duke’s first scholarly communications officer in June of 2006 after fifteen years as a librarian in liberal arts colleges and theological seminaries. Throughout my career as a reference librarian and library director, I was fascinated by copyright, intellectual property licensing, and the array of other legal issues that a modern academic library encounters. When I had the chance to attend law school in the evenings while still retaining my “day job,” I took it, even though I never really planned to practice law in the usual sense. While I was in law school, I became aware of the growing trend among academic libraries to hire people specifically to address scholarly communications; I knew that was the kind of position I had been training for.

Scholarly communications is a broad and vague term, which has different meanings at different institutions. At some colleges and universities, scholarly communications pertains primarily to support for digital publishing or advocacy for open access to scholarship. Both are elements of my position; however, copyright is my principal focus. My background and interest in copyright law meshed well with the perceived need at Duke for someone to assist faculty, staff, and students in complying with copyright.

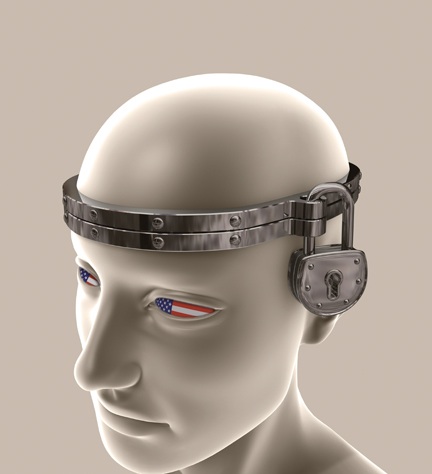

When I first accepted this position, several friends teased me about the title and asked if a scholarly communications officer carried a badge. Good-natured ribbing aside, one of the images I struggle against is that of “copyright cop.” Although my first responsibility is to advise faculty, staff, and students about the application of copyright law to their varied and changing activities, I try to do that without always saying “no.”

Current U.S. copyright law is tremendously restrictive and has not kept up very well with advances in technology. Often the limitations the law imposes on new modes of teaching and learning are very frustrating to both faculty and students. While I sometimes have to uphold those restrictions, I also work at a very practical level to help members of the Duke community, individually and in small groups, to structure projects and courses in ways that will allow them to accomplish their goals without running afoul of the law. In 2007 I had over 250 such consultations.

Smith confers with Associate University Counsel Henry Cuthbert.

Copyright law predominates in these conversations, and the most frequent copyright questions concern the use of materials (print, electronic, audio, and visual) for teaching, especially in electronic course reserves and on Blackboard course sites and external websites like iTunesU. The questions that arise are very “fact-specific” and require careful discussions with faculty about the type of material being used, the amount being copied into the site, extent of access to the materials, and whether or not permission to use the materials is readily available. All these factors are weighed in determining “fair use,” a broad but maddeningly vague and shifting exception to our copyright law. Much of contemporary teaching and learning depends on fair use, but it is nearly impossible to clearly define its boundaries. From my point of view, that uncertainty by itself represents full employment for the scholarly communications officer.

Fair use notwithstanding, many other copyright issues also cross my desk: may a student re-master LP recordings from the 1950s, 60s and 70s as part of a class project? This question is especially difficult to answer since a major change in the protection of copyrighted materials occurred right in the middle of that time period. May the library digitize some comic books published in France by the Nazi propaganda machine in the early 1940s for a digital collection? Inherent in the formation of digital library collections is the core balance that copyright is intended to strike between protecting authors’ interests, especially their ability to profit from their creativity, and the need to use and often repurpose older work in order to support teaching and to encourage new creative endeavors. This particular issue also highlights the tangled relationship amongst the copyright laws of different nations, as well as the various international treaties that are in force, and the sticky question of how to treat a copyright granted by a government that no longer exists.

As much as copyright dominates my work, I also offer assistance to the Duke community in the areas of intellectual property licensing and, especially, scholarly publishing. I am particularly anxious to help scholars navigate the treacherous waters of publication, where technology creates many new opportunities to disseminate scholarly work and publication contracts are all different and change as often as the tides. Sometimes my role is simply to explain the language of publishing contracts to authors so that they have a clear idea of what rights they will, or will not, continue to have in their published works. These days scholars not only want to distribute print copies of their own work to the students they teach, they also may want to put their work on a web page or in a disciplinary repository. They frequently hope to use the work, or the underlying research, in conference presentations, PowerPoint displays, or even in a later book. The ability of an author to take advantage of any of these opportunities will depend on the specific terms of a publication agreement.

As much as copyright dominates my work, I also offer assistance to the Duke community in the areas of intellectual property licensing and, especially, scholarly publishing. I am particularly anxious to help scholars navigate the treacherous waters of publication, where technology creates many new opportunities to disseminate scholarly work and publication contracts are all different and change as often as the tides. Sometimes my role is simply to explain the language of publishing contracts to authors so that they have a clear idea of what rights they will, or will not, continue to have in their published works. These days scholars not only want to distribute print copies of their own work to the students they teach, they also may want to put their work on a web page or in a disciplinary repository. They frequently hope to use the work, or the underlying research, in conference presentations, PowerPoint displays, or even in a later book. The ability of an author to take advantage of any of these opportunities will depend on the specific terms of a publication agreement.

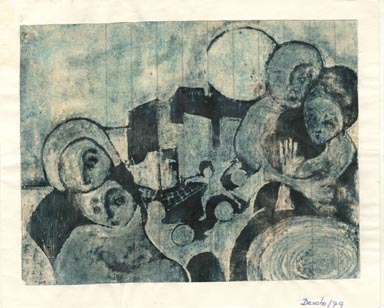

Less frequently, the publication issues I address are much more complex than simply reading a contract, although that can be arduous enough. I have been asked, for example, to help research the copyright status and find the rights holder of one of Thomas Wolfe’s short stories—which he originally sold for the price of a winter overcoat—for a professor who wanted to reprint that story in a book he was writing. I have also helped a faculty member convince her publisher that illustrations she wanted to use in her book about changing images of family life could be republished, as fair use, even when it was not possible to get permission to use all of them. Recently, I was called on to help sort out all of the rights involved (and the paperwork necessary to account for those rights) in creating a translation of a German-language biography of a prominent female physicist of the mid-20th century and publishing that translation on the Web.

New technologies have created intellectual property issues that are difficult to sort out. Podcasts are recordings that are posted on the Internet for people to listen to and download onto portable devices. But may faculty download podcasts in order to insert “chapters” into them so that students can be assigned to listen to parts of the (altered) podcasts without having to search for the appropriate section? And sometimes the questions are low-tech but still thorny. For instance, can a student group interested in global health issues sponsor a documentary film series for other interested students without purchasing a public performance license for each film?

In addition to the individual assistance I offer to faculty and students, I also make quite a few presentations, both on campus and to external groups. I also monitor legislation and court cases that impact the role of intellectual property in higher education so that I can advise the University about how to formulate policy and when to take a stand on some decision pending in Congress or at the U.S. Copyright Office.

Smith addresses graduate students attending a Responsible Conduct of Research forum.

One issue that has arisen only very recently is sure to occupy quite a bit of my attention in coming months. Just after Christmas President Bush signed a massive spending bill that included, buried deep in the appropriations for the Department of Health and Human Services, a clause that will affect researchers who are funded by the National Institutes of Health, which supports more than $20 billion of research each year. The clause requires NIH researchers to deposit copies of the published peer-reviewed articles about their research in the open access PubMed Central database within one year of publication. Open access means that anyone with Internet access can read the articles available in PubMed Central. Congress decided that medical information, especially when it derives from taxpayer-funded research, is too important to disseminate only in highly specialized academic journals that are often very expensive and sometimes held in only a few libraries.

Taxpayer access to publicly funded research sounds like a great idea, and it has the potential to provide a significant public benefit. But there are many questions yet to be answered and many fears to be calmed. Publishers are concerned that public access to the same articles that they are publishing in their journals could further depress subscriptions. The one-year gap allowed between publication and open access availability is designed to reduce this potential impact. Researchers will need to be informed about this new deposit requirement and will need to consider it when they negotiate with publishers. Contracts will have to include clauses to permit this open access deposit along with all the other provisions regarding copyright ownership. Most of all, researchers and authors, who are always busy and have little time for external distractions, will need help with all the aspects of compliance with this new mandate. Providing this assistance will be added to the responsibilities of the scholarly communications officer.

Taxpayer access to publicly funded research sounds like a great idea, and it has the potential to provide a significant public benefit. But there are many questions yet to be answered and many fears to be calmed. Publishers are concerned that public access to the same articles that they are publishing in their journals could further depress subscriptions. The one-year gap allowed between publication and open access availability is designed to reduce this potential impact. Researchers will need to be informed about this new deposit requirement and will need to consider it when they negotiate with publishers. Contracts will have to include clauses to permit this open access deposit along with all the other provisions regarding copyright ownership. Most of all, researchers and authors, who are always busy and have little time for external distractions, will need help with all the aspects of compliance with this new mandate. Providing this assistance will be added to the responsibilities of the scholarly communications officer.

When I became Duke’s scholarly communications officer, I was surprised at how quickly people sought me out to ask questions; I literally had several inquiries waiting for me on my first day at work. Word-of-mouth is still my best “advertising,” but over the past year I have become more assertive about encouraging questions, offering resources and discussing issues. The principal vehicle for this increased communication with potential clients and any other interested readers is a website built around a web log, or blog, that I maintain with help of several library colleagues. “Scholarly Communications @ Duke” (http://library.duke.edu/blogs/scholcomm/) features weekly commentary about a host of issues including copyright and trends in publishing and technological innovations. I also post information about resources related to copyright in the classroom and scholarly publishing. Finally, there are lists of links to many other sites that offer further information and reflection.

With the array of various and complex issues that confront me in my new role, I have to say that it is never boring to be Duke’s scholarly communications officer. Sometimes, when folks want simple answers to complex questions or refuse to accept the best advice I can give, it can be a stressful role. But mostly it is an education and a privilege to be involved in a small way with so many of the diverse classes and scholarly projects that are underway across campus. So how does a scholarly communications officer thrive? By listening carefully in order to understand the underlying need or goal behind each question. By avoiding the easy answer of “not possible” and looking instead for creative ways to facilitate each project. By breaking bad news gently, when it cannot be avoided. And, most importantly, by keeping a sense of humor and gratitude for the good fortune that brought me to Duke.

Kevin Smith is Duke University’s Scholarly Communications Officer.

Read More about Copyright

Duke University Center for the Study of the Public Domain. “Tales from the Public Domain: Bound by Law.” Comic book format discussion of copyright and filmmaking available online at http://www.law.duke.edu/cspd/comics.

Paul Goldstein. Copyright’s Highway: the Law and Lore of Copyright from Gutenberg to the Celestial Jukebox. New York: Hill and Wang, 1994.

Jessica Littman. Digital Copyright. Amherst, NY: Prometheus Books, 2001.

Charles C. Mann. “Who Will Own Your Next Good Idea?” Atlantic Monthly, vol. 282/3 (September 1998): 57-82.

Paul Newman. “Copyright Essentials for Linguists.” Language Documentation and Conservation, vol. 1/1 (June 2007). Online journal article available at http://www.nflrc.hawaii.edu/ldc/June2007/newman/newman.html.

Sive Vaidhynathan. Copyrights and Copywrongs: the Rise of Intellectual Property and How it Threatens Creativity. New York: New York University Press, 2001.

John Willinsky. The Access Principle: the Case for Open Access to Research and Scholarship. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press, 2006.