Human Rights Histories in Duke’s Special Collections Library

by Patrick Stawski

My mother recently sent me a letter which she had come across while cleaning out an over-burdened closet. After reading it and digesting its contents, she knew it would pique the interest of her son, an archivist now curating a human rights collection at Duke University. The letter was written in 1984 in Rosario, Argentina, by my mother’s younger sister, Maria Rosa.  My aunt composed the letter on a manual typewriter, one without a correction ribbon, onto a now browning 5″ by 8.5″ sheet of paper. Large x’s are superimposed over errors and a red pen has been used for the final editing.

My aunt composed the letter on a manual typewriter, one without a correction ribbon, onto a now browning 5″ by 8.5″ sheet of paper. Large x’s are superimposed over errors and a red pen has been used for the final editing.

At a time when Argentina was experiencing not triple but quadruple digit annual inflation, paper and letters were precious. This was also the era of government-run telephone companies when Argentines waited for years, usually in vain, to have a telephone line installed in their homes. Amongst the twenty or so households which made up my family, there was only one home phone in 1984. Understandably, the arrival of a letter such as this one at our adopted home of Anaheim, California, from our relatives in Argentina amounted to a small miracle and would have been greeted with a certain degree of fanfare.

Dated February 14, (later corrected to the 22) 1984, the letter begins with the sort of exchange to be expected between two sisters who find themselves thousands of miles apart: news of brothers, sisters, sisters-in-law, squabbles, bickering, business, and property. But the letter takes an abrupt and dark turn as my aunt tries to describe the discoveries that have been made since civilian rule returned to the country. She reports 10,000 estimated “desaparecidos,” or disappeared (eventually the number would climb to 40,000); numerous clandestine prisons, torture camps; secret cemeteries filled with naked, tortured corpses bound with chains and barbed wire, mostly of young men and women; an entire family, including an eight-year-old girl, each executed with a bullet to the head and their bodies buried beneath the public plaza; “bodies and bodies, everyday in the news…”

Dated February 14, (later corrected to the 22) 1984, the letter begins with the sort of exchange to be expected between two sisters who find themselves thousands of miles apart: news of brothers, sisters, sisters-in-law, squabbles, bickering, business, and property. But the letter takes an abrupt and dark turn as my aunt tries to describe the discoveries that have been made since civilian rule returned to the country. She reports 10,000 estimated “desaparecidos,” or disappeared (eventually the number would climb to 40,000); numerous clandestine prisons, torture camps; secret cemeteries filled with naked, tortured corpses bound with chains and barbed wire, mostly of young men and women; an entire family, including an eight-year-old girl, each executed with a bullet to the head and their bodies buried beneath the public plaza; “bodies and bodies, everyday in the news…”

I mention this letter from my family’s own archives to illustrate from a personal perspective the important and perhaps unexpected nature of human rights documentation that is being collected by the Archive for Human Rights at the Duke Libraries. The disbelief that accompanied the grisly discoveries in Argentina in the 1980s was not unique. Again and again and around the world the uncovering of evidence of massive terror is often accompanied by shock and disbelief. This is precisely because secrecy, disappearance, censoring of independent media, and circumvention of normal legal proceedings and record-keeping protocols are the tools that allow repressive forces to act with impunity. In response, the human rights community has grown into a global network one of whose primary objectives is to counteract silence and the erasing of memory, evidence, and history by monitoring, witnessing, and documenting human rights abuses.

These abuses leave deep and profound scars in communities, families, and individuals. Thus, the substance of human rights history is found not only in organizational and government records but also in family and personal papers. It comprises letters, photos, research files, newspaper clippings, legal documents, even PowerPoint presentations. The diversity of the sources is evidence that human rights and their abuse are not just a matter of government policy and strategies; they are as profoundly personal as they are political. This relationship between the personal and the public is apparent in many of our collections.

These abuses leave deep and profound scars in communities, families, and individuals. Thus, the substance of human rights history is found not only in organizational and government records but also in family and personal papers. It comprises letters, photos, research files, newspaper clippings, legal documents, even PowerPoint presentations. The diversity of the sources is evidence that human rights and their abuse are not just a matter of government policy and strategies; they are as profoundly personal as they are political. This relationship between the personal and the public is apparent in many of our collections.

In the case files of the Center for Death Penalty Litigation (CDPL), for example, researchers can find official police reports and legal affidavits alongside handwritten correspondence between death row inmates and their counsel. The Center for International Policy (CIP) records contain notebooks filled with the firsthand impressions of a CIP associate who traveled to Colombia in 2001 and 2004 to investigate human rights repercussions of the drug wars. The same collection preserves the PowerPoint presentations that CIP created to lobby Congress for changes in U.S. drug trafficking policy.

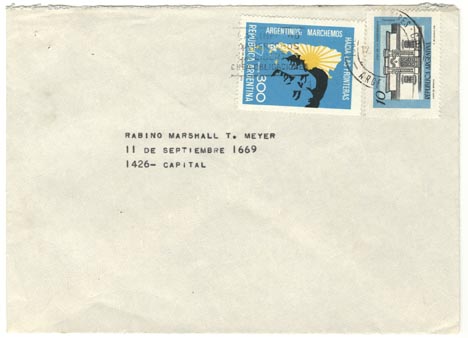

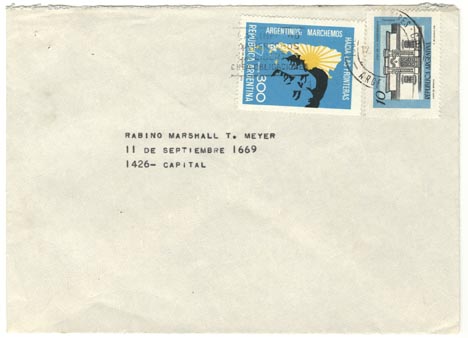

One collection of international significance, and one that I find personally compelling, is the Marshall T. Meyer Papers. The guide to the collection prepared by our staff explains that Marshall Meyer received his education at Dartmouth College and, a year after being ordained rabbi in 1958, moved his family to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where he became rabbi of Comunidad Bet El. During his tenure at Bet El, Meyer reinvigorated Argentina’s Jewish community while living and working through the political and social implosion that rocked Argentina in the 1970s and 1980s.

Progressive, politically engaged, and an activist by nature, Meyer spoke out against the human rights abuses perpetrated under the rule of the military junta. He visited and counseled prisoners in clandestine jails, lobbied national and international authorities for their release, and brought the world’s attention to the crimes being committed by military forces. After the return of democracy to Argentina in 1983, Argentine President Raul Alfonsin recruited Meyer to serve on CONADEP (translated as the National Commission on the Disappearance of Persons), which led a national investigation to establish the extent of the abuses Argentineans suffered under the military junta.

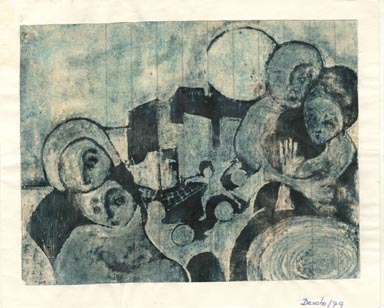

The Meyer papers contain rich documentation representative of the many fronts on which human rights battles are fought. A case in point: in 1977 Argentine police forces entered the house of sixteen-year-old D. and her family, assassinated her brother before her eyes, and then kidnapped her. D. spent over four years in prison without any charges being brought against her before finally being released in 1981 with the help of Meyer and other advocates. The dossier Meyer compiled a as he worked with and for D. provides a record of his negotiation of roadblocks erected by the military and his efforts to help D. maintain her humanity during years in prison.

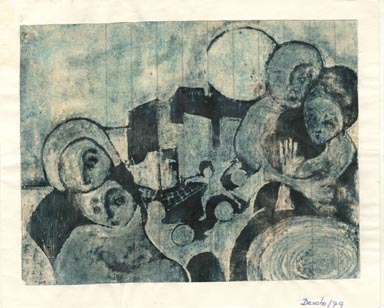

D.’s ink drawing decorates a notecard she made using a piece of lined paper. She sent to card to Rabbi Meyer while she was being held in the Devoto Prison.

On September 30, 1980, Meyer made application to the Canadian Embassy for D.’s immigration to Canada. On December 19, 1980, the second secretary for immigration at the Canadian embassy writes to Meyer’s Seminario Rabinico Latinamericano informing them that the embassy’s request to interview D. has been denied because she has also applied to go to Israel and a decision (by the same military authorities who kidnapped and imprisoned her) has not yet been made on that request. There are many more examples of political action taken on behalf of D. and others: letters to the Dutch and German counsels, to then President Ronald Reagan, and even to the Vatican. Often the letters are accompanied by what must have been disheartening replies that reveal thwarted communication and due process obstructed by vague charges, legal technicalities, and other government-contrived obstacles. Intermingled with these papers is evidence of the profoundly personal side of Meyer’s work: his applications to the government ministries to serve as spiritual counsel for the detained and telegrams to the families of prisoners bearing news of a child or husband’s health, prisoners’ wishes, and sometimes news of a joyous release. Then there are the letters from people like D. in Devoto prison and others like her, detainees who give thanks for a visit or the gift of a book, who describe their treatment or mistreatment, or who express the hope to be reunited one day with loved ones. At times it is clear that the very act of writing the letter has been an act of survival and defiance.

Histories, private and public, embodied in the lives of individuals such as Marshall Meyer or by organizations such as the Center for Death Penalty Litigation or the Center for International Policy, are circulated in the world today in response to the abuse and denial of human rights. Duke’s Archive for Human Rights is dedicated to collecting, and preserving these materials and opening the complex and multi-faceted history of human rights to researchers. Through its work the Archive plays a vital part in maintaining the link between our history and our humanity. For as Marshall Meyer said in a speech in 1991, “…when humans are denigrated, humiliated, and persecuted, the sanctity of human life is threatened everywhere. And if there is no longer the sanctity of life, of human life, we lose our course in history and become less than human.”

Patrick Stawski is the Libraries’ Human Rights Archivist. Visit the Archive for Human Rights online at library.duke.edu/specialcollections/human-rights/.

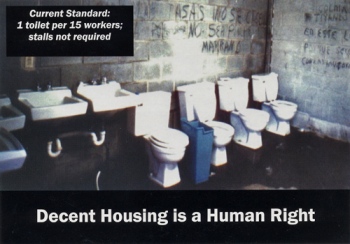

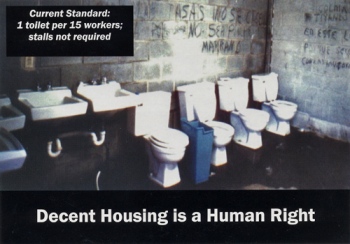

Two items from the Student Action with Farmworkers Records, a collection in the Archive for Human Rights. SAF had its beginnings at Duke in the 1970s when Dr. Robert Coles and Professor Bruce Payne led twelve students in a summer-long migrant project that included an investigation of conditions in North Carolina’s camps for migrant workers.

The Washington Office on Latin America Donates its Archives to the Duke Libraries

The Washington Office on Latin America (WOLA) recently donated its historical archives to the Archive for Human Rights at the Duke Libraries. WOLA is the leading U.S. human rights organization promoting human rights, social justice, and democracy in Latin America. Strong partnerships with colleagues throughout the region inform WOLA’s analysis and foreign policy proposals. Policy makers, elected officials, the media and activisits in both North and Latin America look to WOLA for accurate, timely analysis of U.S. policy and developments in the region.

WOLA was created a year after the 1973 military coup d’etat against the Allende government of Chile, when U.S. activists, church leaders and ordinary citizens came together to push for change in U.S. policies toward Latin America. Today WOLA has a broad agenda that reflects the realities and challenges facing Latin America, ranging from gang violence to organized crime to the effects of free-trade agreements. It works to raise awareness among the U.S. public about how immigration, trade and other issues of concern are linked to problems of poverty and inequality in Latin America.

The agreement with Duke University Libraries provides for the transfer of about 100 boxes of inactive documents and papers from all facets of WOLA’s work. Among the materials coming to Duke are memoranda, correspondence, and publications documenting the organization’s involvement in major issues and events since the 1970s, including the Contra war in Nicaragua, U.S. funding for anti-drug efforts in the Andes, the 1980s civil war in El Salvador, and the Fujimori government in Peru.

Read More about Human Rights

Edwidge Danticat. The Dew Breaker. New York: Distributed by Random House, 2004.

Ariel Dorfman. Heading South, Looking North: A Bilingual Journey. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1998.

Shirin Ebadi. Iran Awakening: A Memoir of Revolution and Hope. New York: Random House, 2006.

Mary Ann Glendon. A World Made New: Eleanor Roosevelt and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. New York: Random House, c2001.

Jean Hatzfeld. Machete Season: The Killers in Rwanda Speak: A Report. Translated from the French by Linda Coverdale; preface by Susan Sontag. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005.

Adam Hochschild. King Leopold’s Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1998.

Claudia Koonz. The Nazi Conscience. Cambridge, MA, Belknap Press, 2003.

Alicia Partnoy. The Little School: Tales of Disappearance and Survival in Argentina. Translated from the Spanish by Alicia Partnoy, with Lois Athey and Sandra Bramstein. London, Virago, 1998, c1986.

Samantha Power. A Problem from Hell: America and the Age of Genocide. New York, Basic Books, c2002.

Helen Prejean. Dead Man Walking: An Eyewitness Account of the Death Penalty in the United States. New York: Vintage Books, 1994.

________. The Death of Innocents: An Eyewitness Account of Wrongful Executions. New York: Random House, c2005.

Jacobo Timerman. Prisoner without a Name, Cell without a Number. Translated from the Spanish by Toby Talbot. New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House.

While the purposes and contents of the projects vary, each incorporates one or more technological application. At the Lakewood Elementary School, 4th and 5th graders, divided into groups, have undertaken related activities focused on preventing the closing of a popular local branch of the YMCA. Teacher Libby Montagne says, “The idea is to work on specific academic goals in a meaningful context as well as develop community organizing and leadership skills.”

While the purposes and contents of the projects vary, each incorporates one or more technological application. At the Lakewood Elementary School, 4th and 5th graders, divided into groups, have undertaken related activities focused on preventing the closing of a popular local branch of the YMCA. Teacher Libby Montagne says, “The idea is to work on specific academic goals in a meaningful context as well as develop community organizing and leadership skills.”