This is the third in a series of blog posts on global pandemics written by Duke Libraries’ International and Area Studies Department. Like the first and second posts, it is edited by Ernest Zitser, Ph.D., Librarian for Slavic, Eurasian, and East European Studies, library liaison to the International Comparative Studies Program, and Adjunct Assistant Professor in the Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies at Duke University. The following blog post is contributed by Carson Holloway, Librarian for History of Science and Technology, Military History, British and Irish Studies, Canadian Studies and General History.

Until COVID-19’s arrival in the United States, Ebola, SARS, MERS, and Zika seemed like diseases of the ‘developing,’ ‘under-governed,’ and ‘less sanitary’ parts for the world. Surely, none of these strange and exotic viruses could ever find a home here, on the soil of the sole remaining superpower, the 20th-century heir of earlier empires on which the sun never set. The residents of late-seventeenth-century London—at the time, the bustling capitol of an up-and-coming maritime power, one that would eventually reach a territorial size larger than any other empire in history—undoubtedly would have agreed with such an assessment of the situation. Deadly tropical diseases afflicted British colonies, not the metropole; and the bubonic plague was a relic of Europe’s ‘dark ages,’ not its enlightened present. Although London did experience sporadic outbreaks of the plague earlier in the century, the residents of the City had been lulled into a false sense of complacency. So it must have come as a great shock when, in the winter of 1665, the Plague re-appeared in the City.

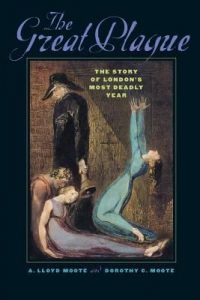

In their engrossing account of what has come to be known as The Great Plague of London, historian A. Lloyd Moote and microbiologist Dorothy C. Moote estimate that between 1665 and 1666, the bubonic plague killed nearly 100,000 city-dwellers, or almost one third of those who did not flee to the countryside. Those urban residents who remained in the City, however, did not panic or put themselves under quarantine. Instead, they continued to fulfill their duties and obligations, keeping as many medical, religious, legal, and business establishments open as long as they possibly could, seemingly unaware that their very activity helped to spread the disease. By using intimate letters and private diaries, and focusing on the personal experience of specific individuals, from all walks-of-life, the Mootes succeed in painting a compelling portrait of an early-modern city—the capitol of the British Empire—dealing (successfully, but at tremendous cost) with an outbreak of a deadly infectious disease.

In their engrossing account of what has come to be known as The Great Plague of London, historian A. Lloyd Moote and microbiologist Dorothy C. Moote estimate that between 1665 and 1666, the bubonic plague killed nearly 100,000 city-dwellers, or almost one third of those who did not flee to the countryside. Those urban residents who remained in the City, however, did not panic or put themselves under quarantine. Instead, they continued to fulfill their duties and obligations, keeping as many medical, religious, legal, and business establishments open as long as they possibly could, seemingly unaware that their very activity helped to spread the disease. By using intimate letters and private diaries, and focusing on the personal experience of specific individuals, from all walks-of-life, the Mootes succeed in painting a compelling portrait of an early-modern city—the capitol of the British Empire—dealing (successfully, but at tremendous cost) with an outbreak of a deadly infectious disease.

Although the current COVID-19 crisis has limited our access to the Duke Library stacks, there are many resources, which can help fill the needs of students and researchers interested in learning more about London’s Great Plague. Primary sources from the period are relatively scarce. In 1665 there were no printed newspapers as we have come to know them; rather, information about the plague was spread by personal letter or by word-of-mouth, and, less often, by such ephemeral publications as broadsides or pamphlets. Fortunately, Duke Libraries subscribe to such research databases as Early English Books Online (EEBO), which provides users with online access to almost all known English-language books and pamphlets published between 1473 and 1700.

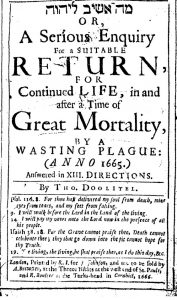

Among the latter are such rare gems as Thomas Doolittle’s 1666 self-help book, הוהיל בישא המ [Heb. = “What shall I return to God”], or, A Serious Enquiry for a Suitable Return for Continued Life, in and after a Time of Great Mortality, by a Wasting Plague (anno 1665) answered in XIII directions, which claims to offer its readers instructions “on how to live life after a wasting plague.” (Just imagine how much money a self-styled life-coach would make if s/he were to publish a 13-step guide to a better life after COVID-19!) Another subscription database, Medieval and Early Modern Sources Online (MEMSO), provides access to other types of English-language primary sources, including family papers and government documents from the period ca. 1100 and 1800, which users can consult in order to find additional contemporary references to the Great Plague.

Among the latter are such rare gems as Thomas Doolittle’s 1666 self-help book, הוהיל בישא המ [Heb. = “What shall I return to God”], or, A Serious Enquiry for a Suitable Return for Continued Life, in and after a Time of Great Mortality, by a Wasting Plague (anno 1665) answered in XIII directions, which claims to offer its readers instructions “on how to live life after a wasting plague.” (Just imagine how much money a self-styled life-coach would make if s/he were to publish a 13-step guide to a better life after COVID-19!) Another subscription database, Medieval and Early Modern Sources Online (MEMSO), provides access to other types of English-language primary sources, including family papers and government documents from the period ca. 1100 and 1800, which users can consult in order to find additional contemporary references to the Great Plague.

In some instances, subscription-based electronic resources such as EEBO and MEMSO can be supplemented by those made freely-available on the internet. For example, the Diaries of Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), one of the primary sources that the Mootes used to such good effect in their book on the London plague, are now available in electronic format through Project Gutenberg, a digital library created in 1971 by volunteers committed to making books in the public domain freely available online. Pepys was an energetic and talented man, who rose from modest beginnings to become the greatest naval administrator of the age, at a time when Britannia was just starting to rule the waves. The private diary that he kept from 1660 until 1669 is one of the most important primary sources for the English Restoration period, providing a combination of frank personal revelations and detailed eyewitness accounts of important public events, including the Great Plague of London. In the early 18th century, Pepys’ manuscript diaries, along with the rest of his personal library, were donated to Magdalene College, Cambridge. But the diaries were not published until almost a century later. And it took yet another century before technological developments made it possible not only to produce a digital version of Pepys’ text but also to publish it online.

In some instances, subscription-based electronic resources such as EEBO and MEMSO can be supplemented by those made freely-available on the internet. For example, the Diaries of Samuel Pepys (1633-1703), one of the primary sources that the Mootes used to such good effect in their book on the London plague, are now available in electronic format through Project Gutenberg, a digital library created in 1971 by volunteers committed to making books in the public domain freely available online. Pepys was an energetic and talented man, who rose from modest beginnings to become the greatest naval administrator of the age, at a time when Britannia was just starting to rule the waves. The private diary that he kept from 1660 until 1669 is one of the most important primary sources for the English Restoration period, providing a combination of frank personal revelations and detailed eyewitness accounts of important public events, including the Great Plague of London. In the early 18th century, Pepys’ manuscript diaries, along with the rest of his personal library, were donated to Magdalene College, Cambridge. But the diaries were not published until almost a century later. And it took yet another century before technological developments made it possible not only to produce a digital version of Pepys’ text but also to publish it online.

Pepys’ eyewitness account of daily life during the plague year records observations and details that would have otherwise been lost to posterity. The following excerpt from a typical day (Friday, 5 January 1665/6), for example, recounts what he saw while riding in a coach on the way to an event in the capitol, in the period immediately after the plague had begun to subside:

And a delightfull thing it is to see the towne full of people again as now it is; and shops begin to open, though in many places seven or eight together, and more, all shut; but yet the towne is full, compared with what it used to be. I mean the City end; for Covent-Guarden and Westminster are yet very empty of people, no Court nor gentry being there.

This version of Pepys’ text comes from Phil Gyford’s groundbreaking blog, which was created in 2003 as a daily transcription of a single day’s entry from the Diary, using the copyright-free text made available online by Project Gutenberg.  Although the British blogger who created this site is not a professional academic — Gyford prefers to call himself an “actor, modelmaker, illustrator and futurist” -– he has created a platform that has attracted the attention of scholars and researchers the world over. Since 2012, when Gyford completed his transcription of Pepys’ Diary, numerous experts have provided annotations to, or written in-depth articles about selected topics brought up in individual diary entries. (For example, clicking the hyperlinked term “the City” in the daily entry quoted above opens a box with an explanatory note about the history of this geographically delimited section within Greater London). Thanks to such contributions, Gyford’s site continues to evolve, thereby providing a good example of the value added by open access electronic resources, which do not lock away the results of scholarly research behind the ‘pay walls’ erected by monopolistic publishers.

Although the British blogger who created this site is not a professional academic — Gyford prefers to call himself an “actor, modelmaker, illustrator and futurist” -– he has created a platform that has attracted the attention of scholars and researchers the world over. Since 2012, when Gyford completed his transcription of Pepys’ Diary, numerous experts have provided annotations to, or written in-depth articles about selected topics brought up in individual diary entries. (For example, clicking the hyperlinked term “the City” in the daily entry quoted above opens a box with an explanatory note about the history of this geographically delimited section within Greater London). Thanks to such contributions, Gyford’s site continues to evolve, thereby providing a good example of the value added by open access electronic resources, which do not lock away the results of scholarly research behind the ‘pay walls’ erected by monopolistic publishers.

Researchers interested in a more literary treatment of the Great Plague would do well to consult A journal of the plague year: being observations or memorials, of the most remarkable occurrences, as well publick as private, which happened in London during the last great visitation in 1665..., available online both via paid subscription to Thomson Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online and for free via Project Gutenberg. This work was written by Daniel Defoe (c.1660-1731), but published, without attribution (under the initials “H.F.”), in 1722. The famed author of Robinson Crusoe (1719) was only about five years old when the Great Plague hit London, so he could not have remembered much of what he and his family had experienced at the time. And yet Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year is described on its title page as a never-before-published memoir by “a citizen who continued all the while in London.” Even the year of publication raises suspicions about the historical authenticity of this self-proclaimed memoir, since the book appeared during a period of high public interest in plagues due to a recent outbreak in France. In other words, what we see here is Defoe in his role as literary entrepreneur, rather than as autobiographer. And yet Defoe’s masterly combination of first-person narration and realistic description (apparently based on substantial historical research), has embroiled scholars in a century-long debate over the question whether Journal of the Plague Year was, in fact, fiction or something more like history.

Researchers interested in a more literary treatment of the Great Plague would do well to consult A journal of the plague year: being observations or memorials, of the most remarkable occurrences, as well publick as private, which happened in London during the last great visitation in 1665..., available online both via paid subscription to Thomson Gale’s Eighteenth Century Collections Online and for free via Project Gutenberg. This work was written by Daniel Defoe (c.1660-1731), but published, without attribution (under the initials “H.F.”), in 1722. The famed author of Robinson Crusoe (1719) was only about five years old when the Great Plague hit London, so he could not have remembered much of what he and his family had experienced at the time. And yet Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year is described on its title page as a never-before-published memoir by “a citizen who continued all the while in London.” Even the year of publication raises suspicions about the historical authenticity of this self-proclaimed memoir, since the book appeared during a period of high public interest in plagues due to a recent outbreak in France. In other words, what we see here is Defoe in his role as literary entrepreneur, rather than as autobiographer. And yet Defoe’s masterly combination of first-person narration and realistic description (apparently based on substantial historical research), has embroiled scholars in a century-long debate over the question whether Journal of the Plague Year was, in fact, fiction or something more like history.

Perhaps the best answer to that question is provided by “H.F.,” the anonymous author of Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, who concludes his “account of this calamitous year …with a coarse but sincere stanza…, which I placed at the end of my ordinary memorandums the same year they were written”:

A dreadful plague in London was

In the year sixty-five,

Which swept an hundred thousand souls

Away; yet I alive!

In the space of four short lines of verse, this brief meditation on mortality manages to encapsulate the complicated mixture of emotions that a survivor of a pandemic must have experienced upon learning the total death count. A moment when the fleeting feeling of joy over one’s own salvation is leavened with grief, loss, and something even more insidious, viz., the nagging, unanswered question: Why was I spared, when so many were taken?

In other words, Defoe’s fictionalized account does not have to be true factually in order to capture and convey the experience of anyone who has ever lived through a catastrophic and traumatic event (such as the one we are currently in). In that sense, A Journal of the Plague Year is as much of a must-read today as it was when first published.

Normally we highlight books from our

Normally we highlight books from our