When Duke professor and botanist Henry J. Oosting agreed to take part in an expedition to Greenland in the summer of 1937 his mission was to collect botanical samples and document the region’s native flora. The expedition, organized and led by noted polar explorer Louise Arner Boyd, included several other accomplished scientists of the day and its principal achievement was the discovery and charting of a submarine ridge off of Greenland’s eastern coast.

In a diary he kept during his trip titled “To Greenland in 105 Days, or Why did I ever leave home,” Oosting focuses little on the expedition’s scientific exploits. Instead, he offers a more intimate look into the mundane and, at times, amusing aspects of early polar exploration. Supplementing the diary in the recently published Henry J. Oosting papers digital collection are a handful of digitized nitrate negatives that add visual interest to his arctic (mis)adventures.

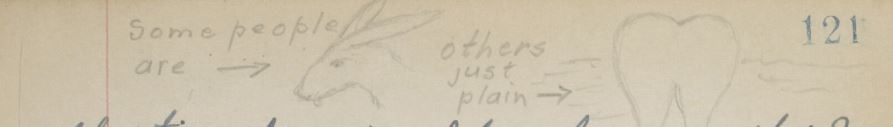

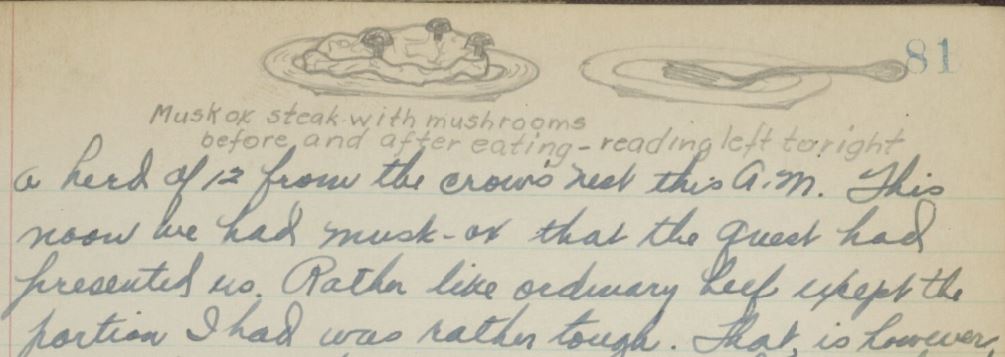

Oosting’s journey got off to an inauspicious start when he wrote in his opening entry on June 9, 1937: “Frankly, I’m not particularly anxious to go now that the time has come–adventure of any sort has never been my line–and the thought of the rolling sea gives me no great cheer.” What follows over the next 200 pages or so, by his own account, are the “inane mental ramblings of a simple-minded botanist,” complete with dozens of equally inane marginal doodles.

The Veslekari, the ship chartered by Louise Boyd for the expedition, first encountered sea ice on July 12 just off the east coast of Greenland. As the ship slowed to a crawl and boredom set in among the crew the following day, Oosting wrote in his diary that “Miss Boyd’s story of the polar bear is worth recording.” He then relayed a joke Boyd told the crew: “If you keep a private school and I keep a private school then why does a polar bear sit on a cake of ice…? To keep its privates cool, of course.” For clarification, Oosting added: “She says she has been trying for a long time to get just the right picture to illustrate the story but it’s either the wrong kind of bear or it won’t hold its position.”

When the expedition finally reached the Greenland coast at the end of July, Oosting spent several days exploring the Tyrolerfjord glacier, gathering plant specimens and drying them on racks in the ship’s engine room. On the glacier, Oosting observed an arctic hare, an ermine, and noted that “my plants are accumulating in such quantity.”

As the expedition wore on Oosting grew increasingly frustrated with the daily tedium and with Boyd’s unfailing enthusiasm for the enterprise. “In spite of everything…we are stopping at more or less regular intervals to see what B thinks is interesting,” Oosting wrote on August 19. “I didn’t go ashore this A.M. for a 15 min. stop even after she suggested it–have heard about it 10 times since…I’ll be obliged to go in every time now regardless or there will be no living with this woman. I am thankful, sincerely thankful, there are only 5 more days before we sail for I am thoroughly fed-up with this whole business.”

By late August, the Veslekari and crew headed back east towards Bergen, Norway and eventually Newcastle, England, where Oosting boarded a train for London on September 12. “This sleeping car is the silliest arrangement imaginable,” Oosting wrote, “my opinion of the English has gone down–at least my opinion of their ideas of comfort.” After a brief stint sightseeing around London, Oosting boarded another ship in Southampton headed for New York and eventually home to Durham. “It will be heaven to get back to the peace and quiet of Durham,” Oosting pined on September 14, “I’m developing a soft spot for the lousy old town.”

Oosting arrived home on September 21, where his diary ends. Despite his curmudgeonly tone throughout and his obsession with recording every inconvenience and impediment encountered along the way, it’s clear from other sources that Oosting’s work on the voyage made important contributions to our understanding of arctic plant life.

In The Coast of Northeast Greenland (1948), edited by Louise Boyd and published by the American Geographic Society, Oosting authored a chapter titled “Ecological Notes on the Flora,” in which he meticulously documented the specimens he collected in the arctic. The onset of World War II and concerns over national security delayed publication of Oosting’s findings, but when released, they provided valuable new information about plant communities in the region. While Oosting’s diary reveals a man with little appetite for adventure, his work endures. As the forward to Boyd’s 1948 volume attests: “When travelers can include significant contributions to science, then adventure becomes a notable achievement.”