In 2013, the average price for a gallon of gas was $3.80, President Obama was inaugurated for a second term, and Duke University Libraries offered DukeSpace as an institutional repository. Some things haven’t changed much, but the preservation architecture protecting the digital materials curated by the Libraries has changed a lot!

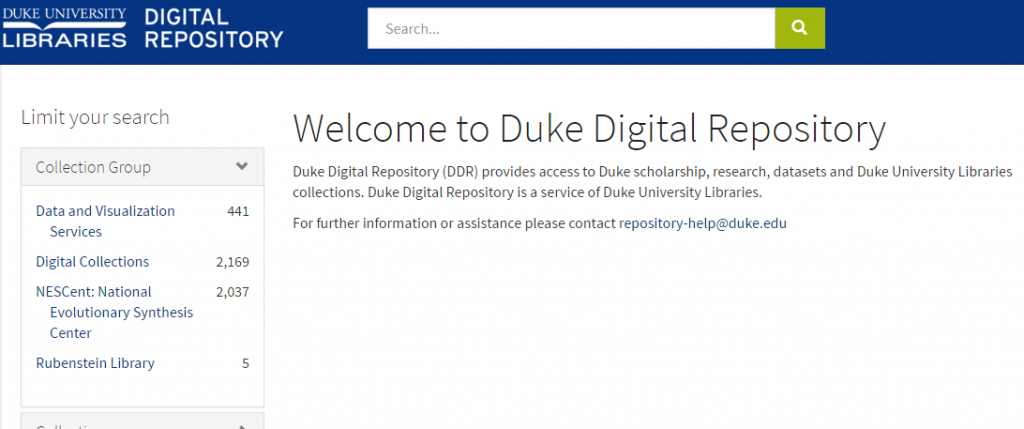

We still provide DukeSpace, but are laying the foundation to migrate collections and processes to the Duke Digital Repository (DDR). The DDR was conceived of and developed as a digital preservation repository, an environment intended to preserve and sustain the rich digital collections; university scholarship and research data; purchased collections, and history of Duke far into the future. Only through the grace of our partnership with Digital Projects and Production Services has the DDR recently also become a site that no longer hurts the eyes of our visitors.

The Duke Digital Repository endeavors to protect our assets from a large and diverse threat model. There are threats that are not addressed in the systems model presented here, such as those identified in the SPOT Model for Risk Assessment, of course. We formally consider these baseline threats to include:

- Natural disasters including accidents at our local nuclear power station, fire, and hurricanes

- Data degradation also known as bit rot or bit decay

- External actors or threats posed by people external to the DDR team including those who manage our infrastructure

- Internal actors including intentional or unintentional security risks and exploits by privileged staff in the libraries and supporting IT organizations

Phase 1 of our ingress into digital preservation established that DSpace, the software powering DukeSpace, was not sufficient for our needs, which led to an environmental scan and pilot project with Fedora and then Fedora and Hydra. This provided us with some of the infrastructure to mitigate the threats we had identified, but not all. In Phase 1 we were to perform some important preservation tasks including:

- Prove authenticity by offering checksum fixity validation on ingest and periodically

- Identify and report on data degradation

- Capture context in the form of descriptive, administrative, and technical metadata

- Identify files in need of remediation using file characterization tools

Phase 2 allows us to address a greater range of threats and therefore offer a higher level of security to our collections. In Phase 2 we’re doing several concurrent migrations including migrating our archival storage to infrastructure that will allow for dynamic resizing, de-duplication, and block-level integrity checking; moving to a horizontally scaled server architecture to allow the repository to grow to meet increasing demands of size (individual file size and size of collection) and traffic; and adopting a cloud replication disaster recovery process using DuraCloud to replace our local-only disk/tape infrastructure. These changes provide significant protection against our baseline threat model by providing geographic diversity to our replicas, allowing us to constantly monitor the health of our 3 cloud replicas, and providing administrative diversity to the management of our replicas ensuring no single threat may corrupt all 4 copies of our data.

More detail about the repository architecture to come.