One of the main areas of emphasis for the CNI Spring 2017 meeting was “new strategies and approaches for institutional repositories (IR).” A few of us at UNC and Duke decided to plug into the zeitgeist by proposing a panel to reflect on some of the ways that we have been rethinking – or even just thinking about – our repositories.

-

Google slidedeck: CNI – April 4, 201

-

As we prepped, we agreed that our approaches to the IR are largely informed by ideas that emerged in the early 2000s. While a number of voices and papers contributed to that thinking, one of the most influential was a piece from 2003, written by CNI Director Clifford Lynch. I provided a citation and brief quote from the paper, and made reference to some of its ideas a few slides later.

We had promised the audience provocative questions, and while this one may seem fairly straightforward, it is probably the most challenging one I face as Program Head of the Duke Digital Repository (DDR).

With the two slides below, I compared Lynch’s statements in 2003 about the scope and content of the institutional repository to the language ]in the DDR mission statement that we wrote last year. I pointed out that they line up fairly well. When we drafted and approved that statement in the DDR Program Committee, we didn’t go back and read the Lynch article. We wrote something that reflected our own point of view, informed by the fifteen years of thinking about and discussing IRs.

What has shifted in the past 12 months or so for us at Duke University Libraries has been our organizational approach. We’ve moved from thinking about the Duke Digital Repository as a platform with a wide range of interested stakeholders, to an umbrella service for three separate program areas. Within those program areas, we can identify five separate streams for collecting or deposit that the Libraries currently support.

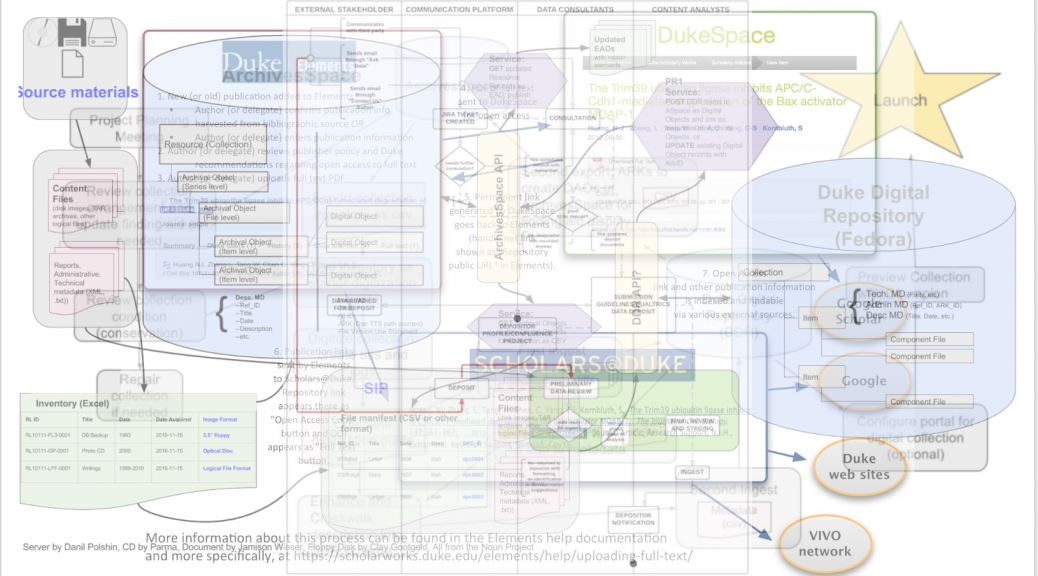

While preparing for the panel, I asked colleagues who manage these streams to share with me any drawings that they had done to represent their processes, and was able to include images for four of the five in my subsequent slides. For fun, I overlaid the four on one another at 25% transparency, and said something like, “When I sit at my desk and just kind of let my vision go blurry, this is what I see.”

But I wanted to make an important point – each of these drawings represents a collecting or depositing area that the library has identified as critical. We devote our most precious resource, the time of our staff members, as well as storage and other commodity resources, to supporting these processes. They represent investments that we make to contribute to our communities and fulfill the library’s mission of stewardship.

The next slide arrays the five established processes around the hub of the DDR, and then adds two more that seem to represent gaps in our stewardship, at least based on what we hear from our stakeholders in the Libraries and on campus. I called them “Library general collections” and “Scholarly products not (research) data or peer-reviewed.”

Next I filled in some detail about the characteristics of these two gap areas. The first area consists “proposed additions to the DDR that originate with the collecting or curatorial activities of staff in the Libraries.” The DDR Program Committee has charged a Library Collections Working Group to consider the problem represented by this areas. These collections consist of materials that may be licensed or purchased by librarians, but have no mode of access for patrons unless we provide it using some technology that’s available to us, such as the DDR.

The second area is characterized by a wide range of requests that we get from our campus community to place materials in the DDR. These requests may come from different levels at the university, and be directed to different levels in the library. They involve a wide range of possible materials, but particularly represent non-traditional forms of scholarship that the library has no established processes for collecting. I see them as characteristic of the output of interdisciplinary centers and other venues where faculty and students are experimenting with new modes of scholarship and inquiry.

When I discussed this second area in my presentation, I mentioned that our University Archives have a commitment to “documentation of University activities” – as is referenced in the DDR mission statement – but their criteria are fairly narrow compared to this more broad demand. Nevertheless, members of our community see these materials as relevant to the vision of “digital repository” that they have in mind. Whether the library chooses to provide stewardship for these materials in the institutional repository or not, I believe we are pressed to organize a response of some kind to this growing demand.

Based on the now fifteen-year history of thinking about institutional repositories that informs our approach, these gaps in stewardship seem to stake some kind of claim to be included in our efforts. Yet if we want to take them on, somebody’s going to have to draw a diagram, and we’re going to need to devote staff time and other resources to supporting those processes. That’s why I concluded my part of the presentation by asking, “Is anyone doing these things?” I’d like to know if any of our colleagues have taken on these areas for their IRs, or even considered and rejected them.

The institutional repository is by now an established concept in the field of librarianship. While we continue to debate the scope and proper function of the IR (see, e.g., Richard Poynder’s “Q&A with CNI’s Clifford Lynch: Time to re-think the institutional repository?”), many of the institutions represented at a meeting like CNI have processes under way like the five I identified at DUL. Now we tackle questions about how to sustain our programs while maintaining our values of service and stewardship, and what new demands and opportunities present themselves.

One thought on “Rethinking Repositories at CNI Spring ’17”

Comments are closed.