Children are smoking in two of my favorite images from our digital collections.

One of them comes from the eleven days in 1964 that William Gedney spent with the Cornett family in Eastern Kentucky. A boy, crusted in dirt, clutching a bent-up Prince Albert can, draws on a cigarette. It’s a miniature of mawkish masculinity that echoes and lightly mocks the numerous shots Gedney took of the Cornett men, often shirtless and sitting on or standing around cars, smoking.

At some point in the now-distant past, while developing and testing our digital collections platform, I stumbled on “smoking dirt boy” as a phrase to use in testing for cases when a search returns only a single result. We kind of adopted him as an unofficial mascot of the digital collections program. He was a mini-meme, one we used within our team to draw chuckles, and added into conference presentations to get some laughs. Everyone loves smoking dirt boy.

It was probably 3-4 years ago that I stopped using the image to elicit guffaws, and started to interrogate my own attitude toward it. It’s not one of Gedney’s most powerful photographs, but it provokes a response, and I had become wary of that response. There’s a very complicated history of photography and American poverty that informs it.

While preparing this post, I did some research into the Cornett family, and came across the item from a discussion thread on a genealogy site, shown here in a screen cap. “My Mother would not let anyone photograph our family,” it reads. “We were all poor, most of us were clean, the Cornetts were another story.” It captures the attitudes that intertwine in that complicated history. The resentment toward the camera’s cold eye on Appalachia is apparent, as is the disdain for the family that implicitly wasn’t “clean,” and let the photographer shoot. These attitudes came to bear in an incident just this last spring, in which a group in West Virginia confronted traveling photographers whom they claimed photographed children without permission.

The photographer Roger May has undertaken an effort to change “this visual definition of Appalachia.” His “Looking at Appalachia” project began with a series of three blog posts on William Gedney’s Kentucky photographs (Part 1, Part 2, Part 3). The New York Times’ Lens blog wrote about the project last month. His perspective is one that brings insight and renewal to Gedney’s work

Gedney’s photographs have taken on a life as a digital collection since they were published on the Duke University Libraries’ web site in 1999. It has become a high-use collection for the Rubenstein Library; that use has driven a recent project we have undertaken in the library to re-process the collection and digitize the entire corpus of finished prints, proof prints, and contact sheets. We expect the work to take more than a year and produce more than 20,000 images (compared to the roughly 5000 available now), but when it’s complete, it should add whole new dimensions to the understanding of Gedney’s work.

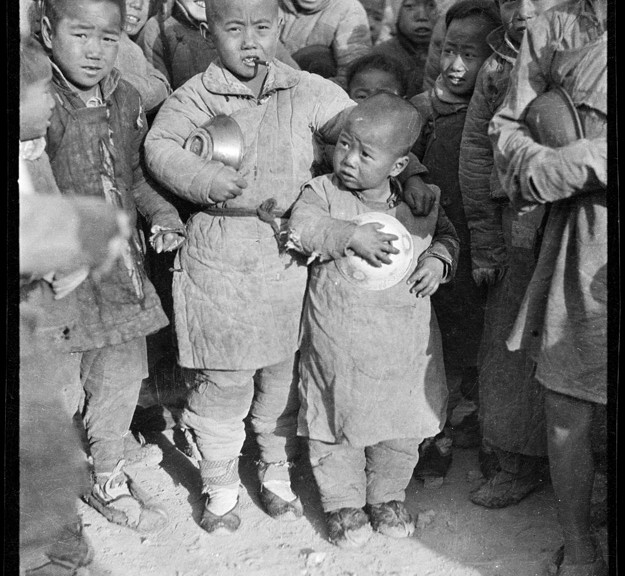

Another collection given life by its digitization is the Sidney Gamble Photographs. The nitrate negatives are so flammable that the library must store them off site, making access impossible without some form of reproduction. Digitization has made it possible for anyone in the world to experience Gamble’s remarkable documentation of China in the early 20th Century. Since its digitization, this collection has been the subject of a traveling exhibit, and will be featured in the Photography Gallery of the Rubenstein Library’s new space when it opens in August.

The photograph of the two boys in the congee distribution line is another favorite of mine. Again, a child is seen smoking in a context that speaks of poverty. There’s plenty to read in the picture, including the expressions on the faces of the different boys, and the way they press their bowls to their chests. But there are two details that make this image rich with implicit narrative – the cigarette in the taller boy’s mouth, and the protective way he drapes his arm over the shorter one. They have similar, close-cropped haircuts, which are also different from the other boys, suggesting they came from the same place. It’s an immediate assumption that the boys are brothers, and the older one has taken on the care and protection of the younger.

Still, I don’t know the full story, and exploring my assumptions about the congee line boys might lead me to ask probing questions about my own attitudes and “visual definition” of the world. This process is one of the aspects of working with images that makes my work rewarding. Smoking dirt boy and the congee line boys are always there to teach me more.

May’s project, and Gonzalez’s NYT blog piece, are worth looking at.

Gamble and Gedney’s work reminds me in some ways of the WPA photographers working during the depression and dust bowl era. Those photogs were sent on assignment to show Americans the “reality” of the conditions fellow Americans were living in (and thereby the most iconic photos tend to be those of the worst living conditions).

But these two collections also remind me in part of reality TV shows like “Jersey Shore” and “Buck Wild.” I think Americans like their stereotypes and prefer the easy road of reinforcing stereotypes rather than acknowledging the societal and economic issues behind the scenes. It’s far easier to stare at “the other” and think, “there but for the grace of god go I” than to acknowledge that these people belong to us. They reflect us as much as the photographer present them to us.

What I like about May’s project is that the evidence of poverty and tough times is still there (and we should be confronted by these images), but there is also a sense of belonging, of place, and of an affection for this area whether we are looking at “the good” or “the bad.” I don’t get that same impression from much of Gamble; and Gedney’s work to some extent feels the same to me. To me, many of their images, while often stunning and beautiful, are also somewhat voyeuristic. The outsider looking in and saying “look at them, ” not the insider saying “look at us.” I suppose this all comes down to intent and purpose.