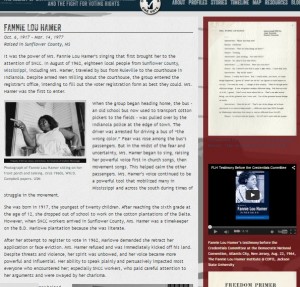

During its first five months, the One Person, One Vote project concentrated on producing content. The forthcoming website (onevotesncc.org) tells the story of how the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee’s (SNCC) commitment to community organizing forged a movement for voting rights made up of thousands of local people. When the One Person, One Vote site goes live on March 2nd (only 17 days from today!), it will include over 75 profiles of the sharecroppers and maids, World War II veterans and high school students, SNCC activists and seasoned mentors that are the true heroes in the struggle for voting rights. From September through January, the project team scoured digital collections, archival resources, secondary sources, and internet leads to craft these stories.

At the end of January, the One Person, One Vote WordPress theme was finished and our url was working. The project had just settled into its new space in The/Edge, Duke Libraries new hub for research, technology, and collaboration, making it a great time to start a new phase of the project: populating and embedding.

Unlike traditional digital collections, the One Person, One Vote site does not host any of the primary source material it uses. Instead, it acts as a digital gateway, embedding and linking to material hosted in different digital collections at institutions across the country. These include the Wisconsin Historical Society’s Freedom Summer Collection, the Civil Rights in Mississippi Digital Archive at the University of Southern Mississippi, Duke’s SNCC 40th Anniversary and Joseph Sinsheimer collections, and the Trinity College’s 1988 SNCC conference tapes to name only a few. Every profile featured on the One Person, One Vote site includes 4 – 8 unique sources, and the entire site has over 400 items embedded in it.

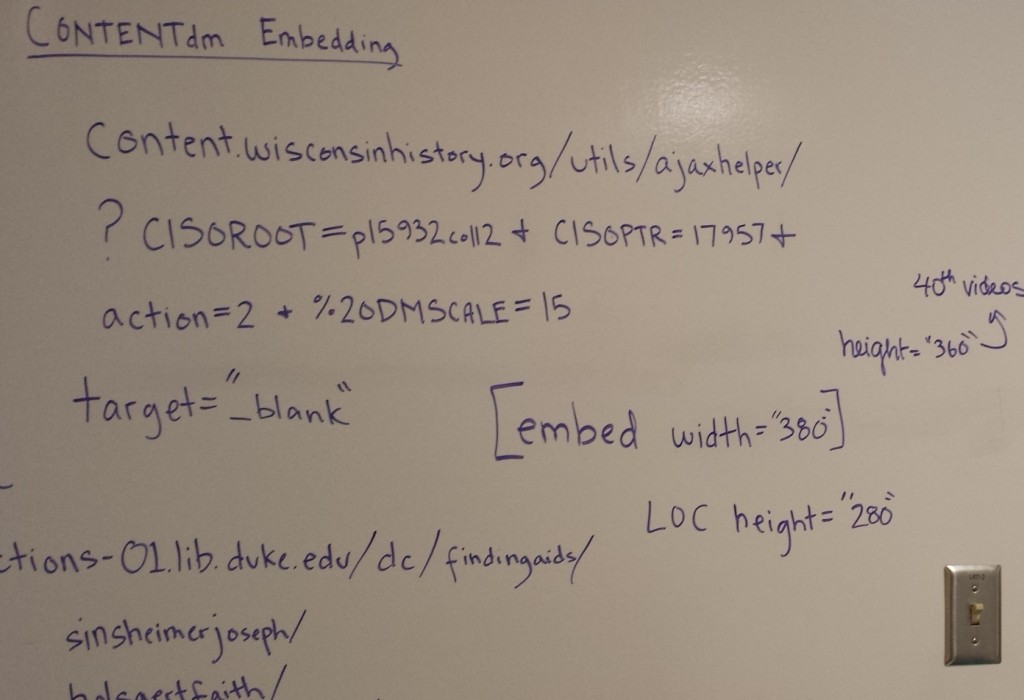

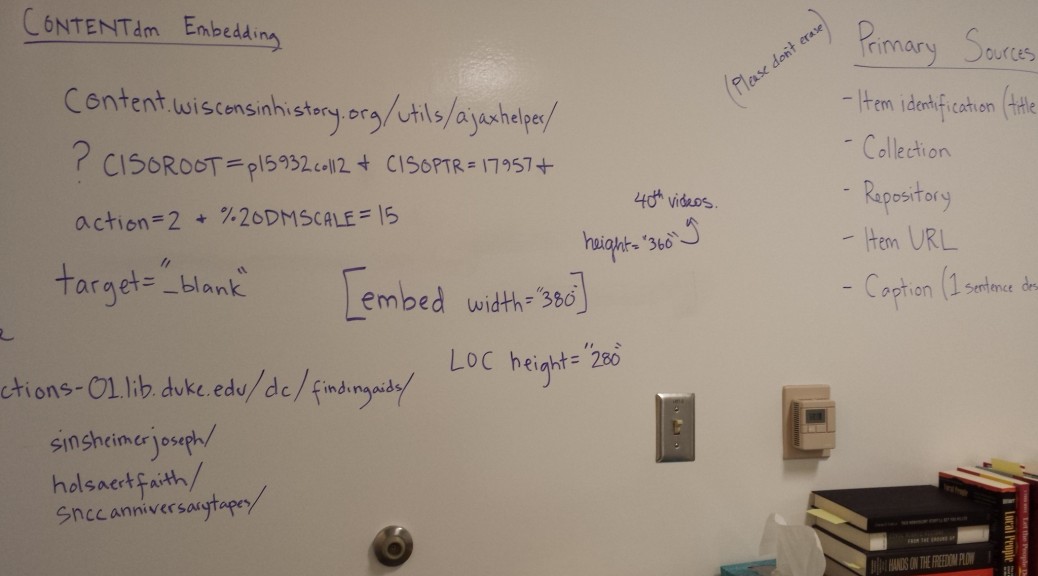

Figuring out how to cleanly and uniformly embed sources has been a challenge to say the least. Many archival institutions use the archival management system, CONTENTdm, to organize their digital collections. The Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement website hosts their documents as pdf files. The Library of Congress provides an embed code for the oral histories in their Civil Rights Oral History Project, but they also post them on YouTube. Meanwhile, the McComb Legacies Project and Trinity College use Vimeo. The amount of digitized material is staggering but how it’s made available is far from standardized. So by trial and error, One Person, One Vote is slowly coming up with answers to the question: how do we bring diverse sources together to tell a compelling story (both narrative-wise and visually) of the grassroots struggle for voting rights? Right now, these are some of our footnotes.