The following is a series of loosely linked stories, loosely based on our digital collections, and loosely related to the holidays, where even the word “loosely” is applied with some looseness.

An American looking forward to baking delicious treats for the holidays in 1942 would have been intimately familiar with War Ration Book One. The Office of Price Administration issued Ration Order No. 3 in April of that year, and distributed the ration books via elementary schools in the first week of May. Holders could purchase one pound of sugar every two weeks between May 5 and June 27. By the end of the year, butter, coffee, and other foods joined the list of regulated goods.

As the holidays approached, the newspapers ran articles advising homemakers how to cope with the unavailability of key ingredients. Vegetable shortening could help stretch butter, molasses made cookies prone to burning, and fruit juice was a natural sweetener. The New Orleans Times-Picayune’s “Round Table Talk About Food” exhorted homemakers to make the best of it:

There is something stimulating this approaching holiday time in planning Christmas meals and gift packages or baskets with those substitute items we are permitted to use, rather than with the usual abundance of foods to suit every whim of the appetite.

I wrote before about how YMCA missionaries took basketball overseas after its invention, including to Japan. Did they also take Santa beards to China?

The Office of Price Administration provided Duke Law alum Richard Nixon with his first job in Washington, beginning in January of 1942. Rubber was his area of focus. He was industrious and diligent in his work, and by March, had been promoted to “acting chief of interpretations in the Rubber Branch.”

But the life of a government regulator was not to be for Dick Nixon. He joined the Navy in August, and by year’s end found himself serving at an airfield in Ottumwa, Iowa.

– Summarized from Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full, by Conrad Black.

True story. Terry Sanford spent December 21 and 22 of 1944 riding in a convoy that took the 1st Battalion of the 517th Parachute Regimental Combat Team from Soissons, France to the town of Soy in Belgium. His unit fought Germans for the next few days, losing more than a hundred men, in the conflagration that became known as the Battle of the Bulge.

They were able to sleep on Christmas Eve. On Christmas morning, there was roasted turkey, but at noon orders came to take a hill, which they did. The next day, they held it, repelling a German counterattack.

In the action, Sanford tackled a German officer, disarmed him, and drove him off for interrogation. Years later, he speculated that the man was probably shot before being processed as a POW, as retaliation against a recent massacre of American troops.

Sanford would write home that “things are going well in this country,” and they had “[m]ore food than elsewhere,” without explaining why there was more to go around.

While riding with his commander, Lt. Colonel “Wild Bill” Boyle, shortly after the New Year, he was wounded. He later received the Purple Heart.

– Summarized from Terry Sanford: Politics, Progress, and Outrageous Ambitions, Howard E. Covington and Marion A. Ellis.

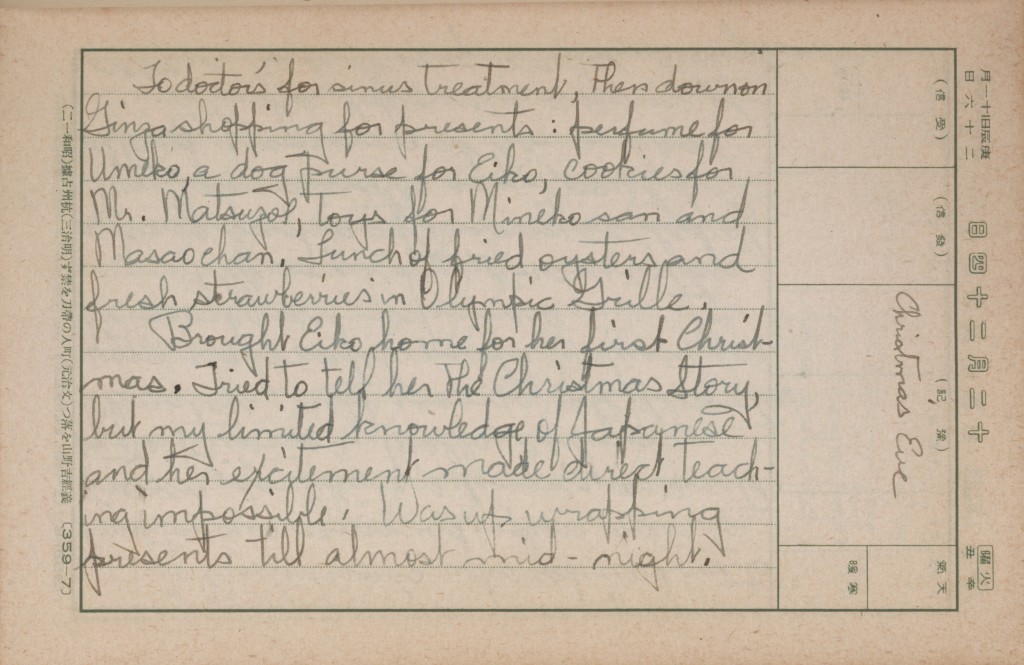

Mary McMillan’s 1940 journal tells of her experiences as a missionary in Japan. Her entry for Christmas Eve of 1940 reads:

To doctor’s for sinus treatment, then down on Ginza shopping for Christmas presents: perfume for Umeko, a dog purse for Eiko, cookies for Mrs. Natsuzoe, toys for Mineko san and Masao chan. Lunch of fried oysters and fresh strawberries in Olympic Grille.

Brought Eiko home for her first Christmas. Tried to tell her the Christmas Story, but my limited knowledge of Japanese and her excitement made direct teaching impossible. Was up wrapping presents till almost mid-night.

A month later she wrote of talks with “Bishop Abe, and Ambassador Grew:”

They advised us to begin making preparations to leave Japan – as is we were certain that war were coming and we were sure to be called home by our Board.”

Her next entry, dated “Feb. 29, ‘41,” is headed “Homeward Bound.”

Variant spellings for hanukkah occur three times in the OCR text of our 1960s Duke Chronicle collection. (Due to the imprecision of OCR, the actual occurrences may be more).

Variant spellings for hanukkah occur three times in the OCR text of our 1960s Duke Chronicle collection. (Due to the imprecision of OCR, the actual occurrences may be more).

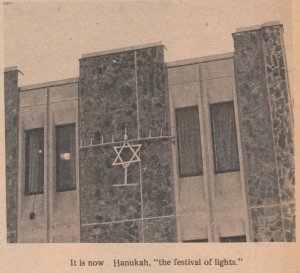

A photograph on the front page of the December 17, 1968, issue depicts a Star of David hanging on the side of a building. The caption reads, “It is now Hanukah, ‘the festival of lights.’”

At the top of that page, the lead story of the issue is headlined, “X-Mas amnesty asked for draft dodgers.” It reports that the “cabinet of the YMCA” at Duke had resolved to write to President Johnson on the matter. Of course, Johnson was a lame duck by then. That same day, the New York Times reported that he had spent an hour conferring with John Mitchell, Nixon’s incoming Attorney General.

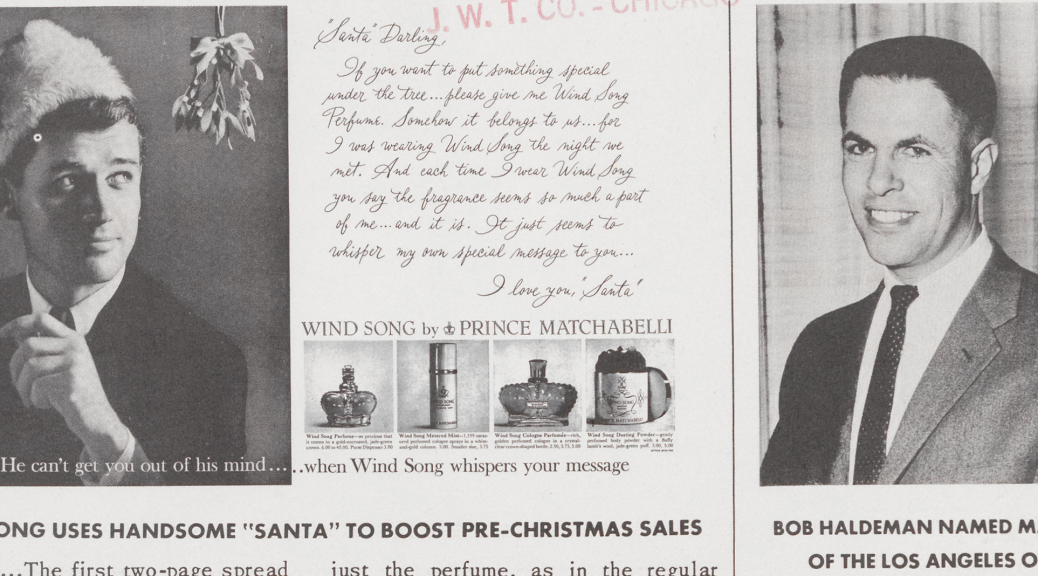

J. Walter Thompson Company News, November 30, 1960, the two lead articles:

J. Walter Thompson Company News, November 30, 1960, the two lead articles:

WIND SONG USES HANDSOME “SANTA” TO BOOST PRE-CHRISTMAS SALES

BOB HALDEMAN NAMED MANAGER OF THE LOS ANGELES OFFICE

Eight years later, the newsletter noted the appointments of Haldeman and his subordinate, Ron Ziegler, to the White House staff. Haldeman would serve as Nixon’s Chief of Staff, and later did 18 months in prison for his role in the Watergate coverup. Ziegler became White House Press Secretary.

On November 17, 1967 – the Friday before Thanksgiving – the Chronicle ran a story about Terry Sanford and his newly published book, Storm over the States. He started writing Storm soon after leaving the NC governor’s office in 1965. Supported by the Ford Foundation and the Carnegie Corporation, he holed up in an office at Duke, hired a staff, and wrote about a model for state government that is federalist but proactive and constructive. Sanford’s point of view stood in stark, if unmentioned, contrast to the doctrines of “nullification” and states’ rights that segregationists like George Wallace wielded in their opposition to Civil Rights.

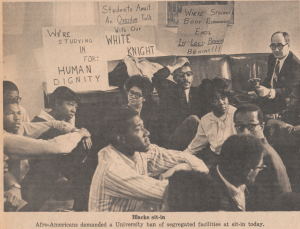

That Friday ended a tumultuous week at Duke. The lead story that same day was headlined “Knight bans use of segregated facilities by student groups.” The school’s president, Douglas Knight, had “re-interpreted” a university policy statement prohibiting the use of off-campus facilities that discriminated on the basis of race. Knight extended the policy, purported to apply to staff and faculty organizations, to include student organizations as well.

The previous week, the student body had defeated a referendum that would have had the same effect. Black students reacted by staging a sit in at Knight’s office (one holding a sign that read “Students Await An Overdue Talk With Our WHITE KNIGHT”), demanding that he take action. Knight acceded, complaining in his statement that “the application of this practice would have been made in the normal course of events,” but “we were confronted with an ultimatum, which carried with it a threat of disruption of the ordinary processes of the University.”

Confrontations between the administration and black students continued to escalate, leading to the Allen Building takeover in 1969, Knight’s resignation, and his succession by Terry Sanford.

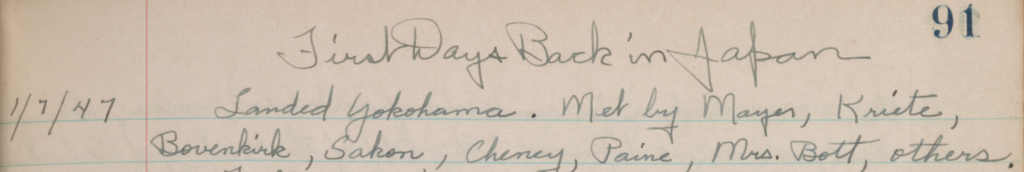

Mary McMillan’s journals stretch from 1939 to 1991. Her “1939” journal actually contains entries from the 1940s, though there are significant gaps. In October of 1942 she wrote of traveling to Delta, Utah. She didn’t mention her purpose, and no other entries appear from that period, but she was heading to Utah to teach in the Topaz Relocation Center, an internment camp for Japanese Americans. En route, she wrote:

Mary McMillan’s journals stretch from 1939 to 1991. Her “1939” journal actually contains entries from the 1940s, though there are significant gaps. In October of 1942 she wrote of traveling to Delta, Utah. She didn’t mention her purpose, and no other entries appear from that period, but she was heading to Utah to teach in the Topaz Relocation Center, an internment camp for Japanese Americans. En route, she wrote:

Those nice Marine recruits who got on our train in St. Louis shouldn’t be required to go so far from home to fight for objectives that seem to me not to be in keeping with United Nations Aims, as given in the Atlantic Charter. Why should Japan “be crushed”? The military mind there – and elsewhere – must be forced from power; but are we on the right track towards achieving that objective? I fear most of us have become too material-minded. By following methods resulting from our materialistic thinking, we only create atmospheres for other hostile “spiritual” forces – like Naziism.

Then, the week of Christmas in 1947 she traveled to Seattle, and embarked on a return to Japan. She arrived in Hiroshima in January, the first Christian missionary to return after the war. She lived there for more than thirty years before retiring.

On page 4 of the December 17, 1967 issue of the Chronicle – just below the article about Terry Sanford’s Storm Over the States – this ad ran:  I have to believe at least a few students and faculty got the book or the record as stocking stuffers that year.

I have to believe at least a few students and faculty got the book or the record as stocking stuffers that year.

“… Richard Nixon … first job in Washington … Rubber was his area of focus.” How prescient, one might say! “Tricky Dicky sure showed some flexibility later in his “career”. He also added “flexibility to the currency by taking the dollar off the gold standard to finance the Vietnam war and/or overcome its aftermath. Then, as improvisations always tend to last, he could never afford to put it back on again. That said, the after-effect seen today is another form of “ration books” – food stamps. However, you cast the above rationing and regulating in a framework of war efforts. That is not entirely the true reasoning. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, at heart a socialist planner who thought that markets have to be “helped along” all the way, started such regulating efforts way back after being first elected and the war just gave him a better screen behind which he could hide his planning phantasies.