The technology for digitizing analog videotape is continually evolving. Thanks to increases in data transfer-rates and hard drive write-speeds, as well as the availability of more powerful computer processors at cheaper price-points, the Digital Production Center recently decided to upgrade its video digitization system. Funding for the improved technology was procured by Winston Atkins, Duke Libraries Preservation Officer. Of all the materials we work with in the Digital Production Center, analog videotape has one of the shortest lifespans. Thus, it is high on the list of the Library’s priorities for long-term digital preservation. Thanks, Winston!

Due to innovative design, ease of use, and dominance within the video and filmmaking communities, we decided to go with a combination of products designed by Apple Inc., and Blackmagic Design. A new computer hardware interface recently adopted by Apple and Blackmagic, called Thunderbolt, allows the the two companies’ products to work seamlessly together at an unprecedented data-transfer speed of 10 Gigabits per second, per channel. This is much faster than previously available interfaces such as Firewire and USB. Because video content incorporates an enormous amount of data, the improved data-transfer speed allows the computer to capture the video signal in real time, without interruption or dropped frames.

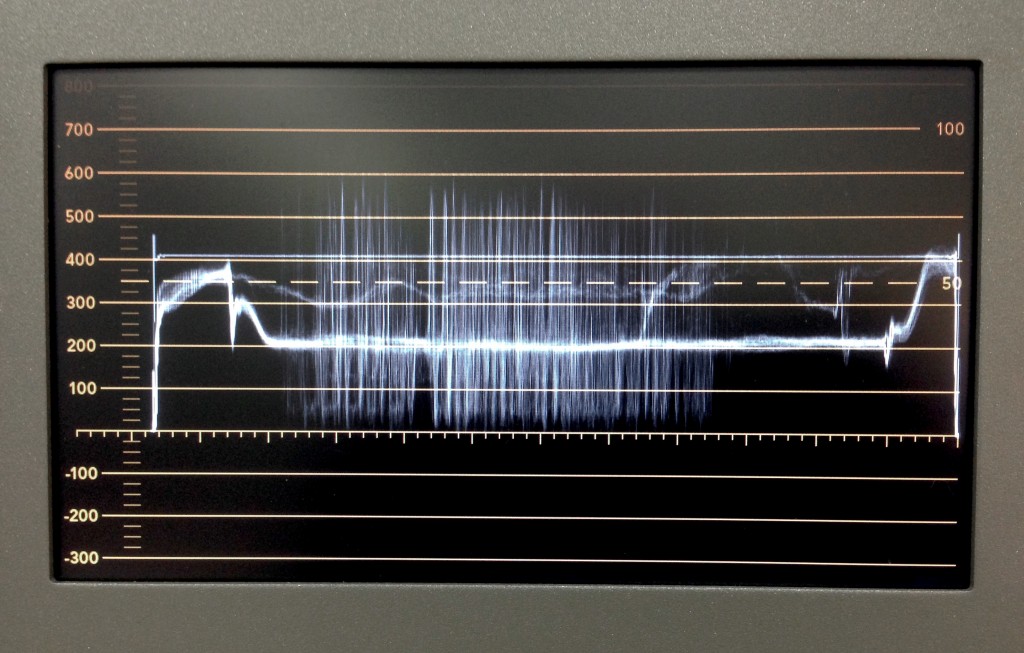

Our new data stream works as follows. Once a tape is playing on an analog videotape deck, the output signal travels through an Analog to SDI (serial digital interface) converter. This converts the content from analog to digital. Next, the digital signal travels via SDI cable through a Blackmagic SmartScope monitor, which allows for monitoring via waveform and vectorscope readouts. A veteran television engineer I know will talk to you for days regarding the physics of this, but, in layperson terms, these readouts let you verify the integrity of the color signal, and make sure your video levels are not too high (blown-out highlights) or too low (crushed shadows). If there is a problem, adjustments can be made via analog video signal processor or time-base corrector to bring the video signal within acceptable limits.

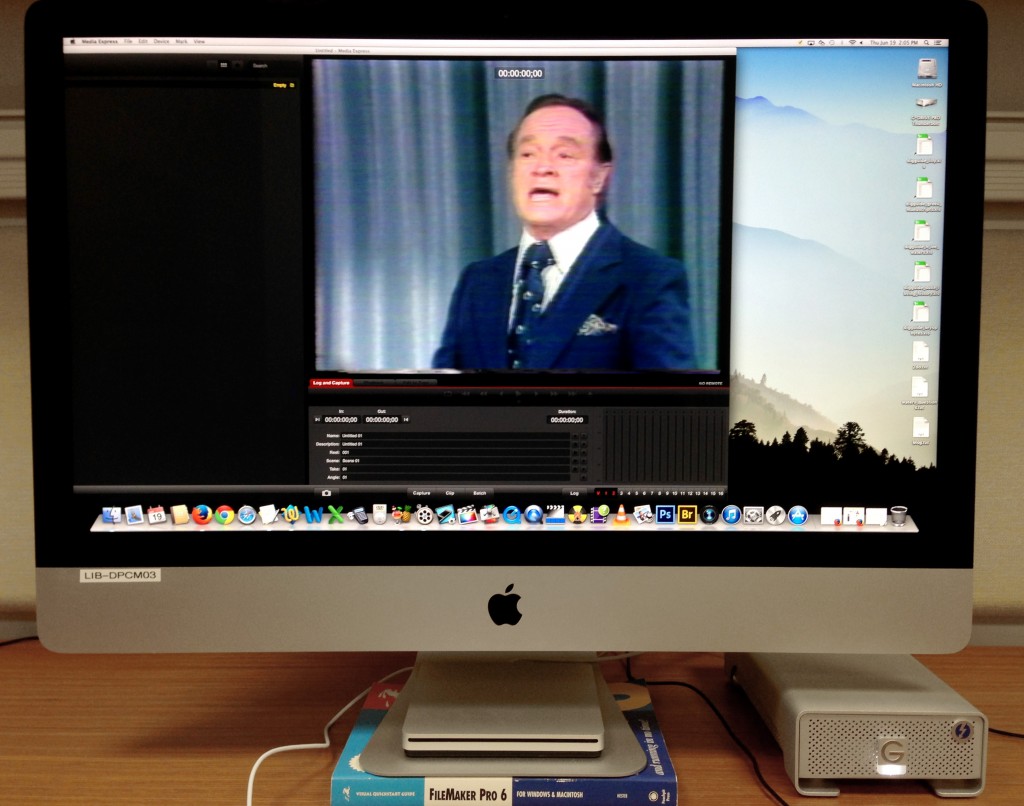

Next, the video content travels via SDI cable to a Blackmagic Ultrastudio interface, which converts the signal from SDI to Thunderbolt, so it can now be recognized by a computer. The content then travels via Thunderbolt cable to a 27″ Apple iMac utilizing a 3.5 GHz Quad-core processor and NVIDIA GeForce graphics processor. Blackmagic’s Media Express software writes the data, via Thunderbolt cable, to a G-Drive Pro external storage system as a 10-bit, uncompressed preservation master file. After capture, editing can be done using Apple’s Final Cut Pro or QuickTime Pro. Compressed Mp4 access derivatives are then batch-processed using Apple’s Compressor software, or other utilities such as MPEG-Streamclip. Finally, the preservation master files are uploaded to Duke’s servers for long-term storage. Unless there are copyright restrictions, the access derivatives will be published online.