Over the last few months, we’ve been doing some behind-the-scenes re-engineering of “the way” we publish digital objects in finding aids (aka “collection guides”). We made these changes in response to two main developments:

- The transition to ArchivesSpace for managing description of archival collections and the production of finding aids

- A growing need to handle new types, or classes, of digital objects in our finding aid interface (especially born-digital electronic records)

Background

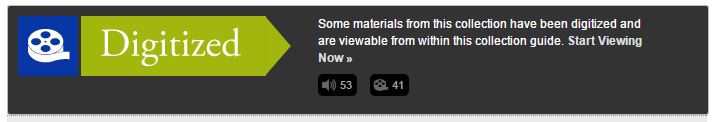

While the majority of items found in Duke Digital Collections are published and accessible through our primary digital collections interface (codename Tripod), we have a growing number of digital objects that are published (and sometimes embedded) in finding aids.

Finding aids describe the contents of manuscript and archival collections, and in many cases, we’ve digitized all or portions of these collections. Some collections may contain material that we acquired in digital form. For a variety of reasons that I won’t describe here, we’ve decided that embedding digital objects directly in finding aids can be a suitable, often low-barrier alternative to publishing them in our primary digital collections platform. You can read more on that decision here.

EAD, ArchivesSpace, and the <dao>

At Duke, we’ve been creating finding aids in EAD (Encoded Archival Description) since the late 1990s. Prior to implementing ArchivesSpace (June 2015) and its predecessor Archivists Toolkit (2012), we created EAD through some combination of an XML editor (NoteTab, Oxygen), Excel spreadsheets, custom scripts, templates, and macros. Not surprisingly, the evolution of EAD authoring tools led to a good deal of inconsistent encoding across our EAD corpus. These inconsistencies were particularly apparent when it came to information encoded in the <dao> element, the EAD element used to describe “digital archival objects” in a collection.

As part of our ArchivesSpace implementation plan, we decided to get better control over the <dao>–both its content and its structure. We wrote some local best practice guidelines for formatting the data contained in the <dao> element and we wrote some scripts to normalize our existing data before migrating it to ArchivesSpace.

Classifying digital objects with the “use statement.”

In June 2015, we migrated all of our finding aids and other descriptive data to ArchivesSpace. In total, we now have about 3400 finding aids (resource records) and over 9,000 associated digital objects described in ArchivesSpace. Among these 9,000 digital objects, there are high-res master images, low-res use copies, audio files, video files, disk image files, and many other kinds of digital content. Further, the digital files are stored in several different locations–some accessible to the public and some restricted to staff.

In order for our finding aid interface to display each type of digital object properly, we developed a classification system of sorts that 1) clearly identifies each class of digital object and 2) describes the desired display behavior for that type of object in our finding aid interface.

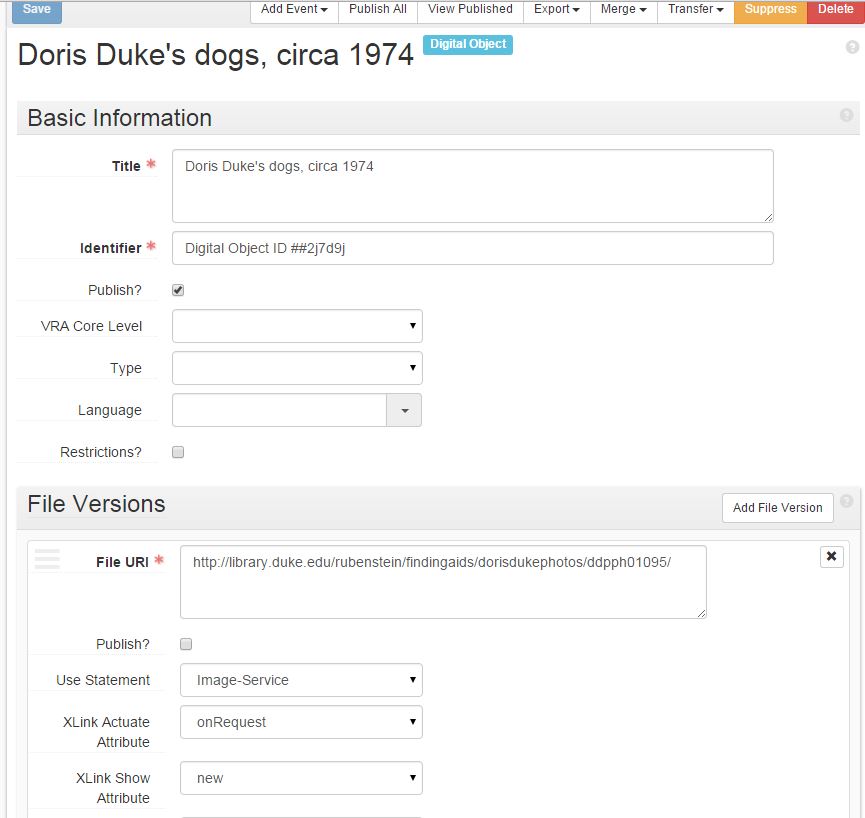

In ArchivesSpace, we store that information consistently in the ‘Use Statement’ field of each Digital Object record. We’ve developed a core set of use statement values that we can easily maintain in a controlled value list in the ArchivesSpace application. In turn, when ArchivesSpace generates or exports an EAD file for any given collection that contains digital objects, these use statement values are output in the DAO role attribute. Actually, a minor bug in the ArchivesSpace application currently prevents the use statement information from appearing in the <dao>. I fixed this by customizing the ArchivesSpace EAD serializer in a local plugin.

Every object its viewer/player

The values in the DAO role attribute tell our display interface how to render a digital object in the finding aid. For example, when the display interface encounters a DAO with role=”video-streaming” it knows to queue up our embedded streaming video player. We have custom viewers and players for audio, batches of image files, PDFs, and many other content types.

Here are links to some finding aids with different classes of embedded digital objects, each with its own associated use statement and viewer/player.

- Jazz Loft Project Records, 1950-2012 (embedded streaming audio and video player)

- Faith Holsaert Papers, 1950-2011 (embedded high-res document viewer–diva.JS–with panning and zooming)

- Asa and Elna Spaulding Papers, 1909-1997 (embedded document viewer with grid view of thumbnails)

- History of Medicine Artifacts Collection, 1550s-1980s (embedded low-res images with slideshow viewer)

- Video for Social Change Oral History Collection, 2014 (embedded video and PDF viewer for transcripts)

- University Archives Web Archive Collection, 2010-ongoing (simple links to web captures in Internet Archive)

- Stephanie Strickland Papers, 1955-2015 (links to “requestable” electronic records like email captures and disk images – still in development)

The curious case of electronic records

The last example above illustrates the curious case of electronic records. The term “electronic records” can describe a wide range of materials but may include things like email archives, disk images, and other formats that are not immediately accessible on our website, but must be used by patrons in the reading room on a secure machine. In these cases, we want to store information about these files in ArchivesSpace and provide a convenient way for patrons to request access to them in the finding aid interface.

Within the next few weeks, we plan to implement some improvements to the way we handle the description of and access to electronic records in finding aids. Eventually, patrons will be able to view detailed information about the electronic records by hovering over a link in the finding aid. Clicking on the link will automatically generate a request for those records in Aeon, the Rubenstein Library’s request management system. Staff can then review and process those requests and, if necessary, prepare the electronic records for viewing on the reading room desktop.

Conclusion

While we continue to tweak our finding aid interface and learn our way around ArchivesSpace, we think we’ve developed a fairly sustainable and flexible way to publish digital objects in finding aids that both preserves the archival context of the items and provides an engaging user-experience for interacting with the objects. As always, we’d love to hear how other libraries may have tackled this same problem. Please share your comments or experiences with handling digital objects in finding aids!

[Credit to Lynn Holdzkom at UNC-Chapel Hill for coining the phrase “The Tao of the DAO”]

Hi Noah,

Thanks so much for your post, it’s really helpful. I’m really impressed by your custom interface layout as well – I think it’s really lovely and clean looking. Can you tell me what your content management system and viewer is? We’re using digitool as our CMS and using its inbuilt viewer, but it’s almost at the end of it’s lifespan, so we’re looking at potential alternatives at the moment, and it would be great to get a bit of insight into the level of customisability in other systems.

Thanks,

Emily