Post contributed by Wenrui Zhao, a Ph.D. candidate in the History Department at Columbia University and a History of Medicine Collections travel grant recipient

What did people know about the anatomy of our eyes and the causes of eye diseases in Europe in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries? How did they understand vision and think about the sense of sight? My dissertation “Dissecting Sight: Eye Surgery and Vision in Early Modern Europe” tries to answer these questions. Thanks to a generous History of Medicine travel grant, I could consult the wonderful collections at the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library to support my project.

The absolute highlight of my visit is the book Ophthalmodouleia, das ist Augendienst by the German surgeon Georg Bartisch, published in 1583 in Dresden. It is one of the earliest publications on eye diseases and eye surgery, and is written in vernacular German. Bartisch was a man of modest upbringing who never received university medical training, yet he was appointed oculist to the Elector of Saxony late in his life.

Bartisch’s treatise is about the mechanism of seeing, but also enacts an experience of seeing. The most striking feature of this book is the great number of finely-executed illustrations alongside the texts. These woodcuts depict various subjects related to ocular disorders and surgical techniques. The Rubenstein Library has one of the very few hand-colored copies of this treatise. While I have already seen this edition in black and white elsewhere, examining this beautiful hand-colored copy was a very different experience and brought new insights.

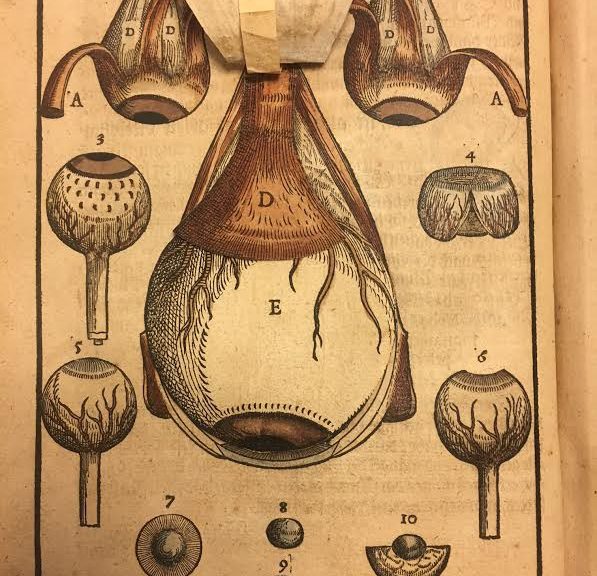

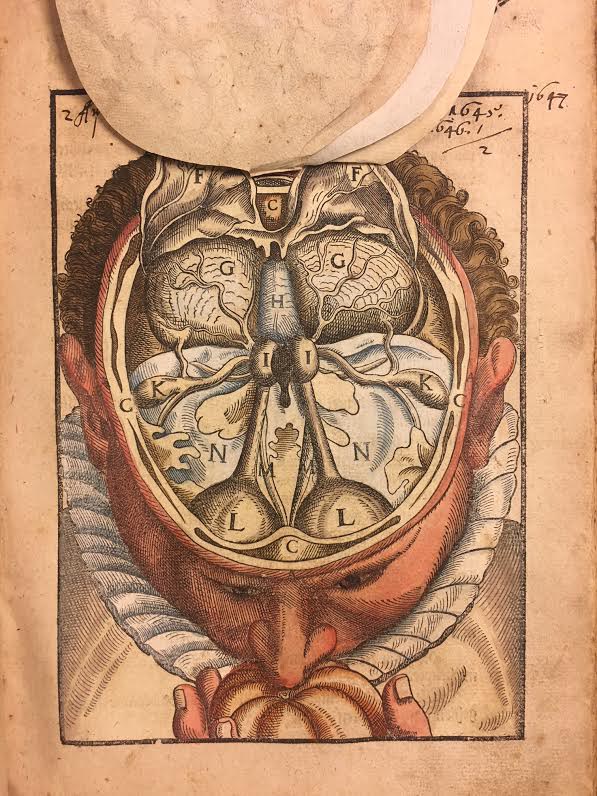

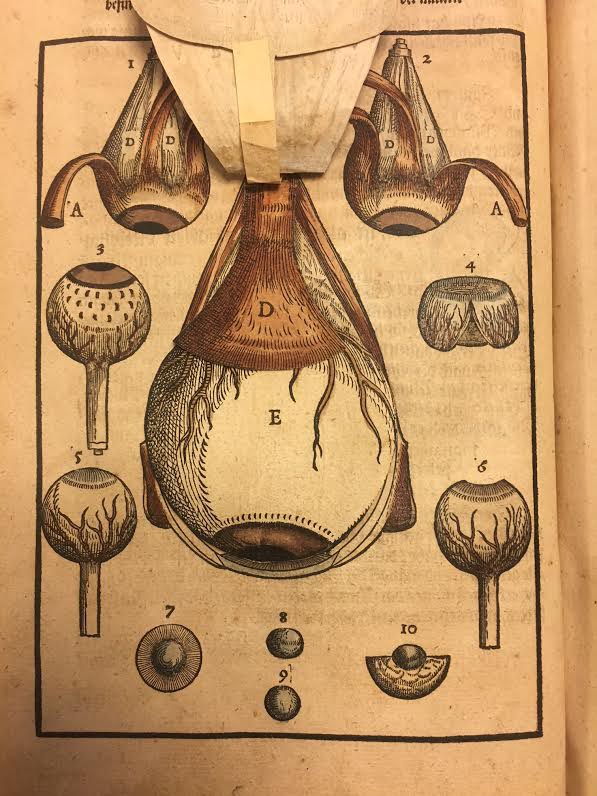

Two sets of the illustrations are movable flaps, representing the internal structure of the head and the anatomy of the eye respectively. The red blood vessels, light brown iris, and the meticulous shading and cross-hatching help distinguish different parts of the eye. They evoke the ocular surgical procedure, and prompt the readers to ponder their own faculty of vision when they lift these sheets layer by layer.

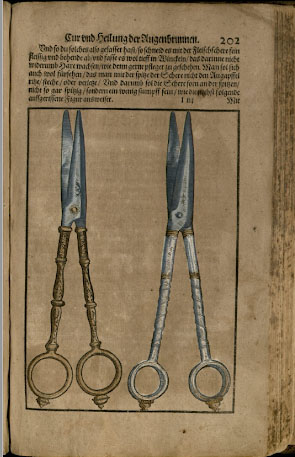

Some of the images representing surgical tools were even heightened by gold and silver, such as this pair of scissors, thereby accentuating their intricate and elegant design.

Some of the images representing surgical tools were even heightened by gold and silver, such as this pair of scissors, thereby accentuating their intricate and elegant design.

Bartisch’s Ophthalmodouleia represents an emergent interest in the anatomy and physiology of the eye from the late sixteenth century. It also serves as a great example of how medical knowledge could be visualized and communicated at that time.