Kids across North Carolina will begin trudging back to school this month, trading in the freedom of summer for the mysteries of the hypotenuse and iambic pentameter. Many of them will, of course, be asking that age-old question: why do I have to learn this? As a young North Carolinian, I frequently puzzled over the usefulness of math, plate tectonics, and why knowing that President Taft got stuck in a bathtub was so essential to my educational development. Did my predecessors complain about school? Undoubtedly. What would they have been complaining about? That is the question this post sets out to answer.

The Rubenstein Library holds many items that offer a glimpse into North Carolina school rooms during the 19th century. Schools of the past would be unrecognizable to students today. Early North Carolina schools were rarely described in positive terms and helped contribute to the state’s reputation as the “Rip van Winkle state.” Until the 1880s, public education in the state was a local affair. County school boards reigned supreme while the state superintendent had little power and remained a distant figure in Raleigh. School funds were largely raised at the local level and many school buildings were built by local community members. Schools were small, often just a single room, and operated in four-month sessions to accommodate students who were needed on the family farm. The curriculum for young North Carolinians reflected the common school model that was popular in 19th century America. Students of all ages and levels were taught in one classroom by one teacher who relied on memorization and repetitive oral exercises to educate the group. A student learned at his own pace, and grades, as we think about them today, did not exist. There was also an emphasis on moral instruction. Local communities saw schools as the place (other than church) to form good, responsible citizens for the future.

As it did with most aspects of American life, the Civil War brought change to the classroom. This transformation was slow- attempts to improve the school system were hampered by the state’s poverty following the war and budget woes that lingered into the 1870s and 1880s. But as the state slowly became a more urban one, railroads extended their reach, and industrial growth offered new lines of work, state leaders recognized that a new educational model was needed if the state was to join the modern “New South.” To that end, school reformers turned to the graded school model that first took hold in antebellum New England. Graded schools were based on standardization. Students were promoted to a new grade level only after they had met a certain criteria. Written examinations, rather than public oral recitations, became a way of marking progress and obtaining a good grade was necessary for academic success. Memorization gave way to an emphasis on students understanding the information and being able to apply what they had learned. The first graded schools in North Carolina opened around 1870, but began to spread across the state in the 1880s and 1890s

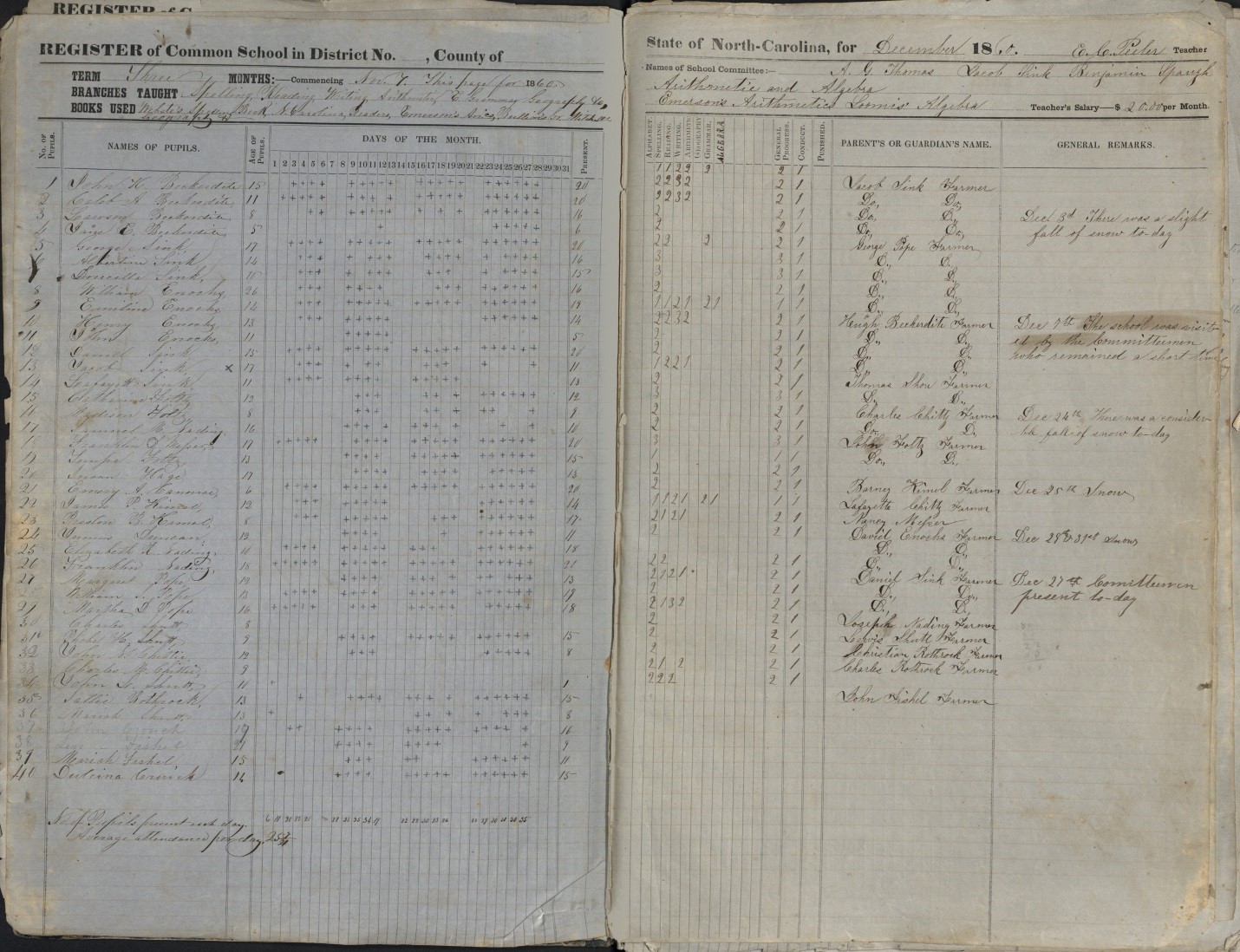

The school register shown above provides a place for teachers to list the “books used” for instruction. The Rubenstein Library has a number of these registers from across the state and a fairly long list of textbooks used by students can be generated through the registers. Luckily for us, the library holds many of the listed titles.

If I had been a student in the 19th century, The Elements of Algebra would have been my least favorite textbook. Unlike the large math textbooks of today, this volume fits easily in one hand and is filled with text. Problems are immediately followed by solutions. The equations and steps needed to solve the problem are rarely shown. The problems are strikingly practical. For children in the rural South, learning to calculate the number of oxen a farmer purchased would seem like a useful skill. Calculating the length of cloth or the division of a man’s estate upon his death would also have been familiar to students.

Like math books, spelling books or spellers are commonly listed in the registers. The state of North Carolina published its own speller in 1892 and it is a surprisingly good read. Described as “a complete graded course in orthography,” this book was a product of the state’s graded school movement. Tailored to North Carolina classrooms, the preface explains that the book is intended to “aid Southern children in acquiring the pure language of America as it is found in the South.” In addition to listing practice words of increasing complexity, the book provides passages and poems that can be used to practice spelling the words in context. These chunks of text are often quotes from prominent North Carolinians, like Zebulon Vance, or lofty odes to the wonders of the state. My particular favorite is the anonymous passage that says “You must love your State very much. It is the best land on earth for a good home. Do not think that you can find more joy in some State far off, for all who go from our State soon want to come back.”

Geography seems like it would have been the most fun subject for students. Matthew Fontaine Maury’s geography books were popular and heavily illustrated. Maury’s First Lessons in Geography takes students on a trip around the world. One lesson begins with an invitation: “Would you like to go to sea? Suppose we take an imaginary voyage from Norfolk to Spain, that certain things may be explained to you, and your lessons made easier to learn.” Readers are taken on a journey through all of the continents and make brief stops to learn about each area. During a stop in China, students would learn about foot binding, rice, and religious beliefs. Writing in the late 1870s, Maury, unsurprisingly, has few good things to say about non-Western people. The Chinese, for instance, are described as starving “heathens.” Maury, however, can hardly find anything negative to say about England, France, or, of course, the United States.

We’ve come a long way from the one-room school house. Our textbooks and school records look significantly different than they did in the 19th century. It has been a while since I took the SAT, but I doubt casks of brandy or “the pure language of America as it is found in the South” were involved. While the lack of constant standardized testing and four month school terms may seem exciting to students today, I remain grateful that I went to school in a time of air conditioning and indoor plumbing.

Sources:

Leloudis, James L. Schooling the New South: Pedagogy, Self, and Society in North Carolina, 1880-1920. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1996.

Post contributed by Brooke Guthrie, Research Services Coordinator.