As the Josiah Charles Trent Intern for the History of Medicine Collections, I have the opportunity to work with closely with a number of rare books, manuscripts and artifacts spanning hundreds of years and several continents. Because I’m here for a brief period of time, I’ve had to immerse myself in the materials in order to become familiar with them. While learning about the breadth and depth of the collections, one item in particular stood out to me: the nkisi nkondi figure in the History of Medicine artifacts collection.

Nkisi nkondi figures come from the Kongo people, a Bantu ethnic group located in the present-day Democratic Republic of the Congo. Nkisi are spirits or objects that spirits inhabit, and nkondi are an aggressive subclass of nkisi that are used to punish wrongdoing and enforce oaths.

The figures were created collaboratively between sculptors and spiritual specialists called nganga. The wooden figure would be carved by the sculptor, and they could range in size from less than a foot tall, like the figure in the Trent Collection, to lifesize. The sculptor would create a cavity in the head or stomach, which then would be packed with materials chosen for their spiritual significance, such as dirt from an ancestor’s grave. The cavity would then be covered by a mirror or glass, which was believed to allow the spirit to peer through into our world. The figures were often created at the edge of a village because it was the borders and entrances that needed to be protected from outside harm.

The nails in the figure indicate the number of times the spirit was invoked. The spirit would then hunt down wrongdoers, such as thieves or an oath breaker. Nkisi nkondi were used publicly by entire villages and tribal leaders and were intended to protect the innocent. Use by an individual for private gain was considered to be witchcraft.

Although nkisi nkondi figures have been made since at least the sixteenth century, the nailed figures which are predominantly found in western collections were most likely made in the northern region of the Kongo cultural area during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Prior to the availability of nails, nganga would invoke the spirit through other means such as banging two figures together.

During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, colonizers from Belgium, France, and Portugal viewed the figures as weapons of resistance. Missionaries removed them through coercion, or force if necessary, in an effort to remove what was seen as their pagan influence over villagers. Most figures found in western collections were removed during this time period. Because of this history, provenance of the figures can prove to be elusive. Today, the beliefs that underlie these figures still exist, but they no longer take these elaborate forms.

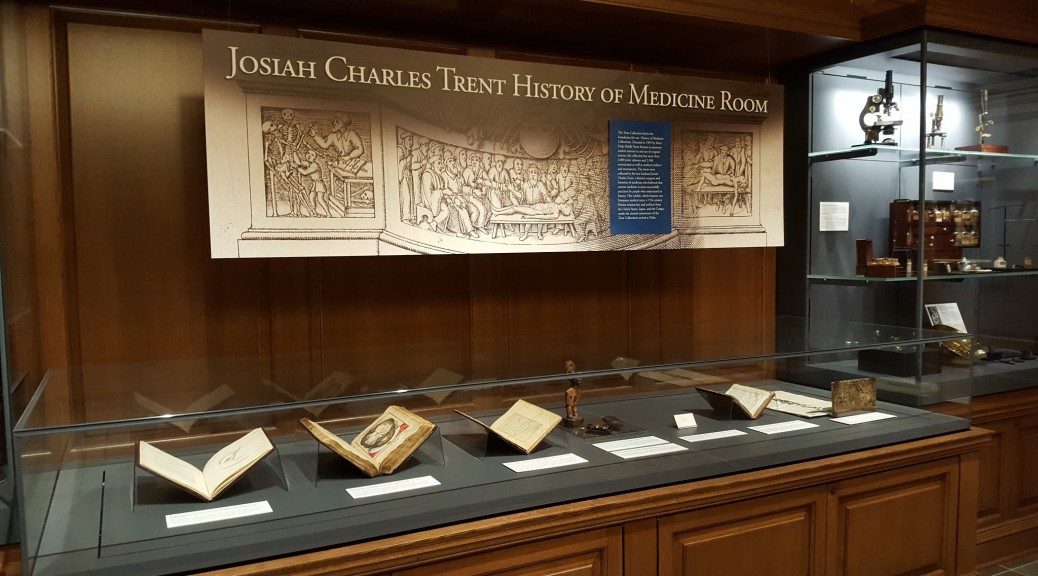

The nkisi nkondi figure is currently on display in the Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine Room as part of an exhibit celebrating the sixtieth anniversary of the collection’s arrival at Duke University, which will be up through the end of June.

Post contributed by Amelia Holmes, Josiah Charles Trent Intern for the History of Medicine Collections