The recent Moral Monday civil protests being held at the state legislature in Raleigh has become national news. Since late April, roughly 700 more protestors have been arrested at the civil disobedience demonstrations. The leadership of clergy within the Moral Monday movement–including Rev. William Barber II, President of the North Carolina State Conference of the NAACP–calls attention to the historical role of the church in civil disobedience and racial justice struggles, both in North Carolina and nationally.

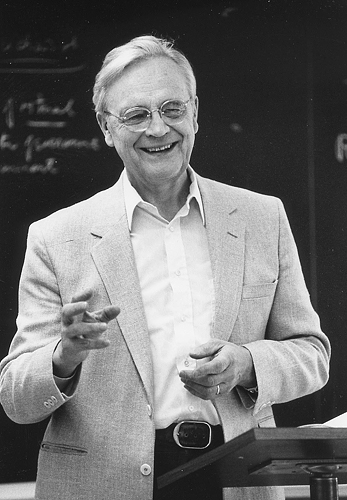

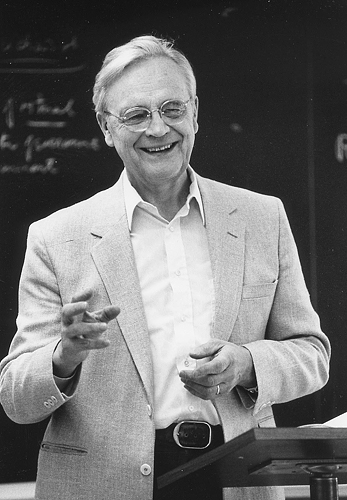

The Frederick Herzog Papers at the Rubenstein Library provide just such a history. A review of the collection situates the Moral Monday protests within the radical traditions of clergy–particularly Protestant ministers but also rabbis and priests–established during the civil rights era and the ability of the Church to organize and influence direct action. Herzog was a liberation theologist and, from 1960 until his death in 1995, a professor at Duke Divinity. Ordained in the ministry of the United Church of Christ, Herzog played an active role in the civil rights struggles in North Carolina in the 60s. His papers give detailed accounts of not only his reflections but also reflections by various others on “wrestling with the role of the church in the face of current racial tensions . . .” (Letter from A.M. Pennybacker, a minister with Heights Christian Church in Shaker Heights, Ohio).

The Frederick Herzog Papers at the Rubenstein Library provide just such a history. A review of the collection situates the Moral Monday protests within the radical traditions of clergy–particularly Protestant ministers but also rabbis and priests–established during the civil rights era and the ability of the Church to organize and influence direct action. Herzog was a liberation theologist and, from 1960 until his death in 1995, a professor at Duke Divinity. Ordained in the ministry of the United Church of Christ, Herzog played an active role in the civil rights struggles in North Carolina in the 60s. His papers give detailed accounts of not only his reflections but also reflections by various others on “wrestling with the role of the church in the face of current racial tensions . . .” (Letter from A.M. Pennybacker, a minister with Heights Christian Church in Shaker Heights, Ohio).

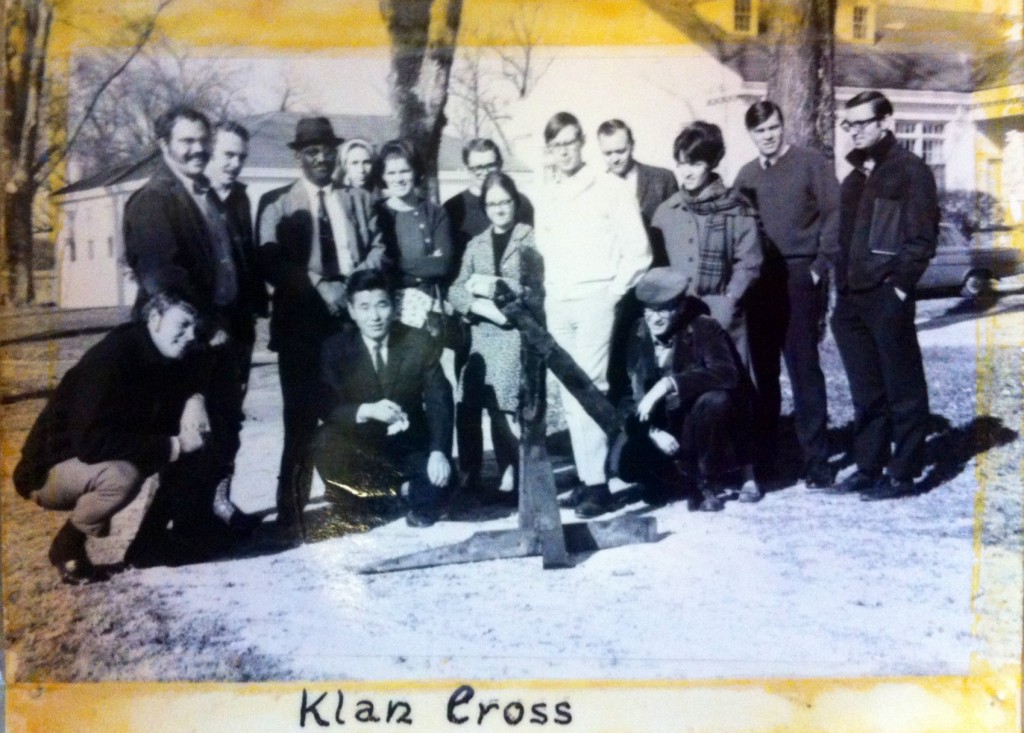

On January 3, 1964, Herzog and ten others were arrested on trespass charges for participating in a sit-in demonstration at a restaurant just outside Chapel Hill to protest segregation. They were beaten and hosed and spent a night in jail. The court offered to commute the sentences of several of the protestors if they affirmed that they would not take part in such demonstrations again. Herzog’s colleagues, William Wynn of the University of North Carolina and Robert Osborn of Duke University refused to say, for theological and moral reasons, that they felt they did not have the right to break the law. They were sentenced to 90 days in the county jail. Herzog, however, affirmed that he could not take part in such action again.

Herzog writes in a brief statement “Christian Witness and a Sit-In” (filed in the Papers under Writings and Speeches) that he initially understood his civil disobedience as an attempt “to fulfill rather than to break the law,” turning to both the Gospels and Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. for justification of his act. Yet Herzog goes on to observe that the arrests of the apostles and Christ’s persecution were “not part of a technique of nonviolence or a planned civil disobedience campaign. It was the result of taking seriously the obligation to witness to Christ.” Their acts were not, in other words, a “crusade against only one specific injustice or wrong.” Herzog comes to the conclusion that this articulation of the Gospel was missing from his “attempt on January 3rd to witness to greater social justice.”

In his statement, Herzog further distinguishes between the refusal to obey a direct requirement of the state and the direct testing of existing laws, the latter which, he argues, characterized his participation in the sit-in. “Is it possible that civil disobedience is a misnomer when applied to this type of activity?” Herzog nevertheless affirms the necessity of reexamining “the forms in which the Christian witness finds expression in the protest movement” and concludes that marching to jail with our fellow men is only a partial solution. We must also, he states, become personally responsible for one another: “The person to person effort has to be tied to new political groups that in the democratic process openly engage in reshaping the societal structures.”

Moral Mondays do not constitute a crusade against one specific injustice but rather employ the broader language of offering a place in society to our most disenfranchised citizens. Herzog’s statement nevertheless complicates and deepens the relationship between theology and protest, and prompts me to ask where Moral Mondays fall within his distinction between refusing to obey and direct testing? Would Herzog classify the occupation of the Capitol as civil disobedience?

Post contributed by Clare Callahan, Rubenstein Technical Services student assistant.