by Erin Hammeke, Senior Conservator

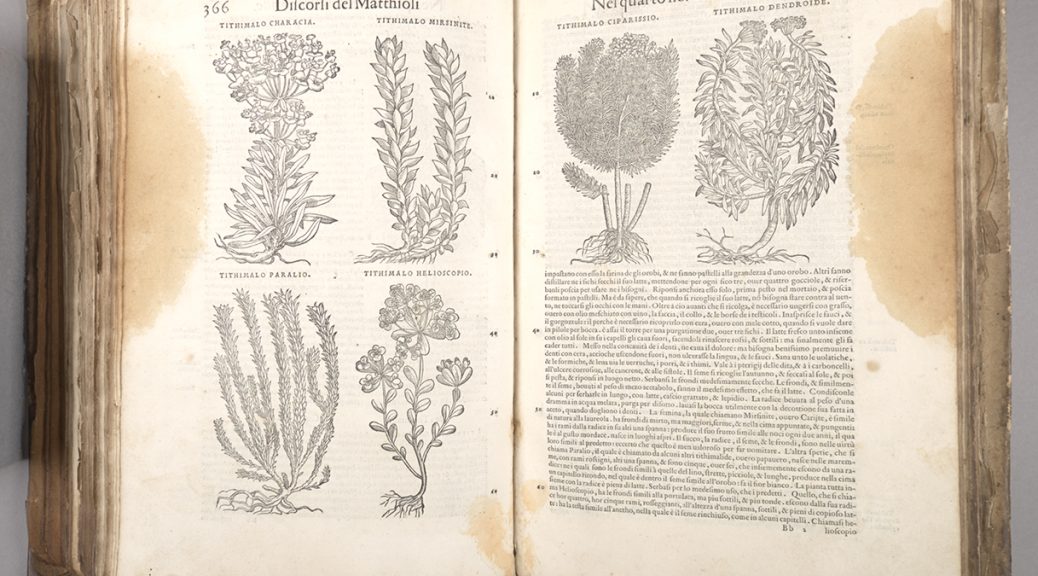

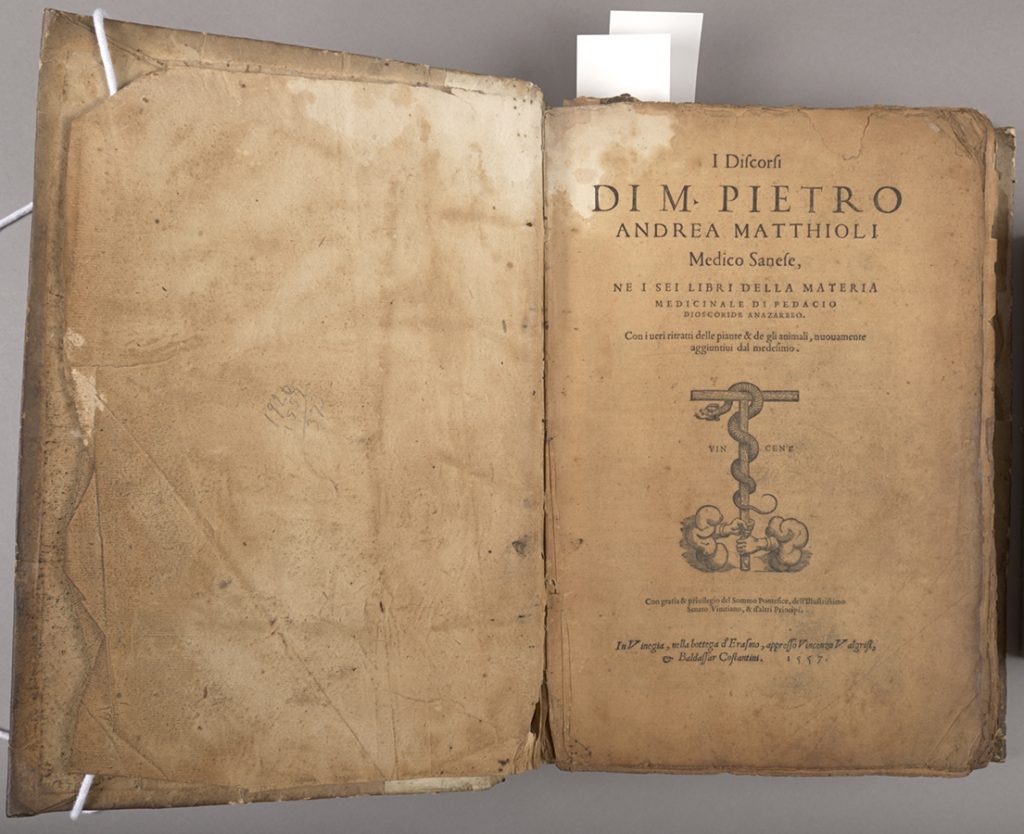

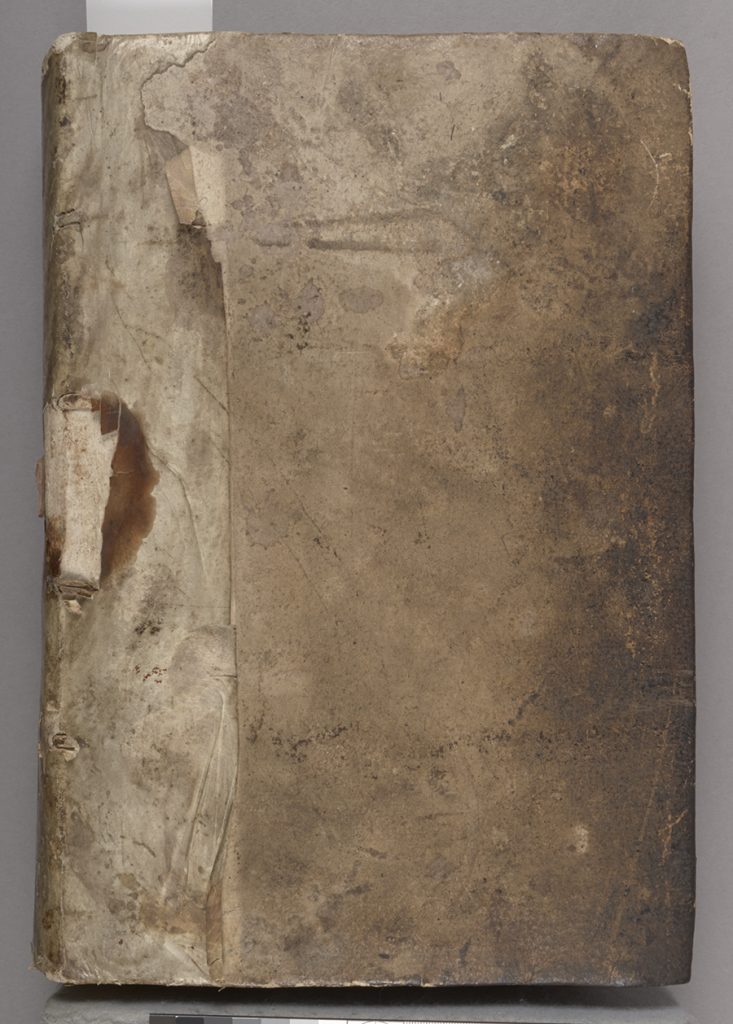

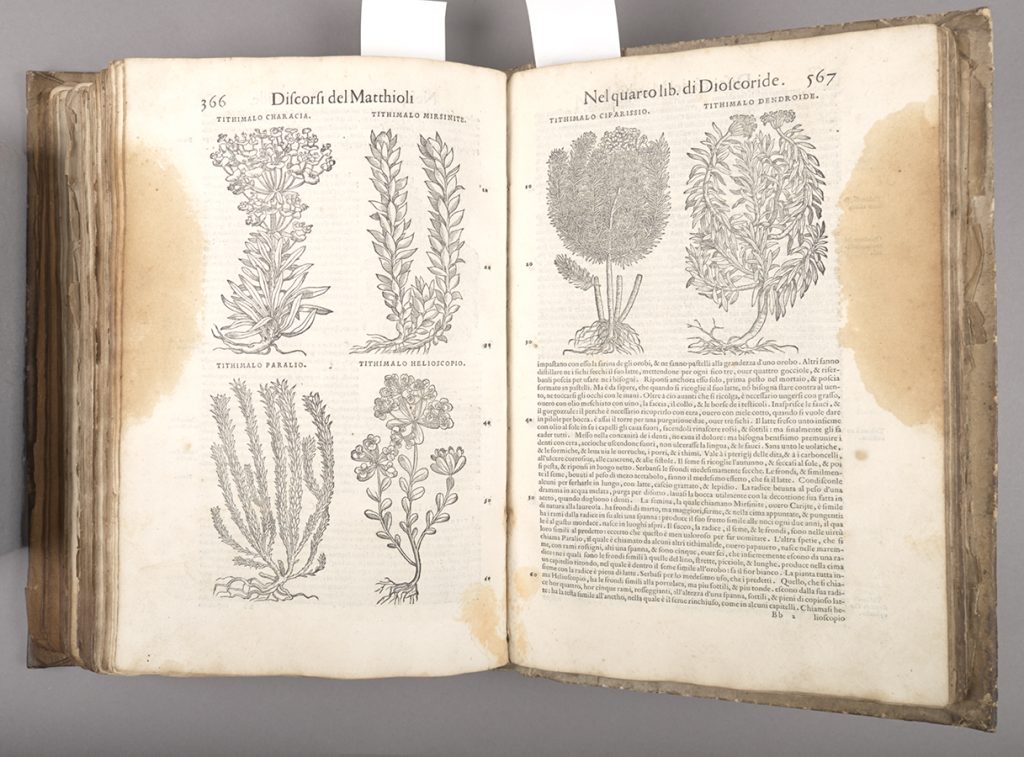

We’re preparing to launch another batch of treatment documentation in the CDA, and the process has reminded me of one of the most complicated, and ultimately, one of my favorite treatments from over the years. I discorsi di M. Pietro Andrea Matthioli, medico senese, … is an early Italian natural medicine text, printed in Venice in 1557. It contains lovely woodcut illustrations of animal and plant species that offered medicinal remedies. Rubenstein Libraries’ copy was acquired for the History of Medicine Collection in 2016 from a family in the Piedmont region of North Carolina.

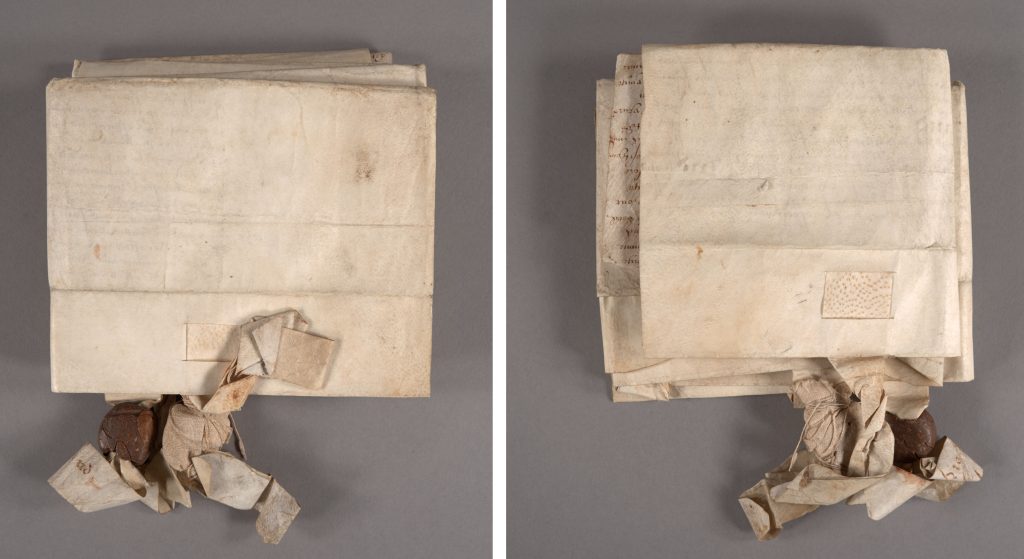

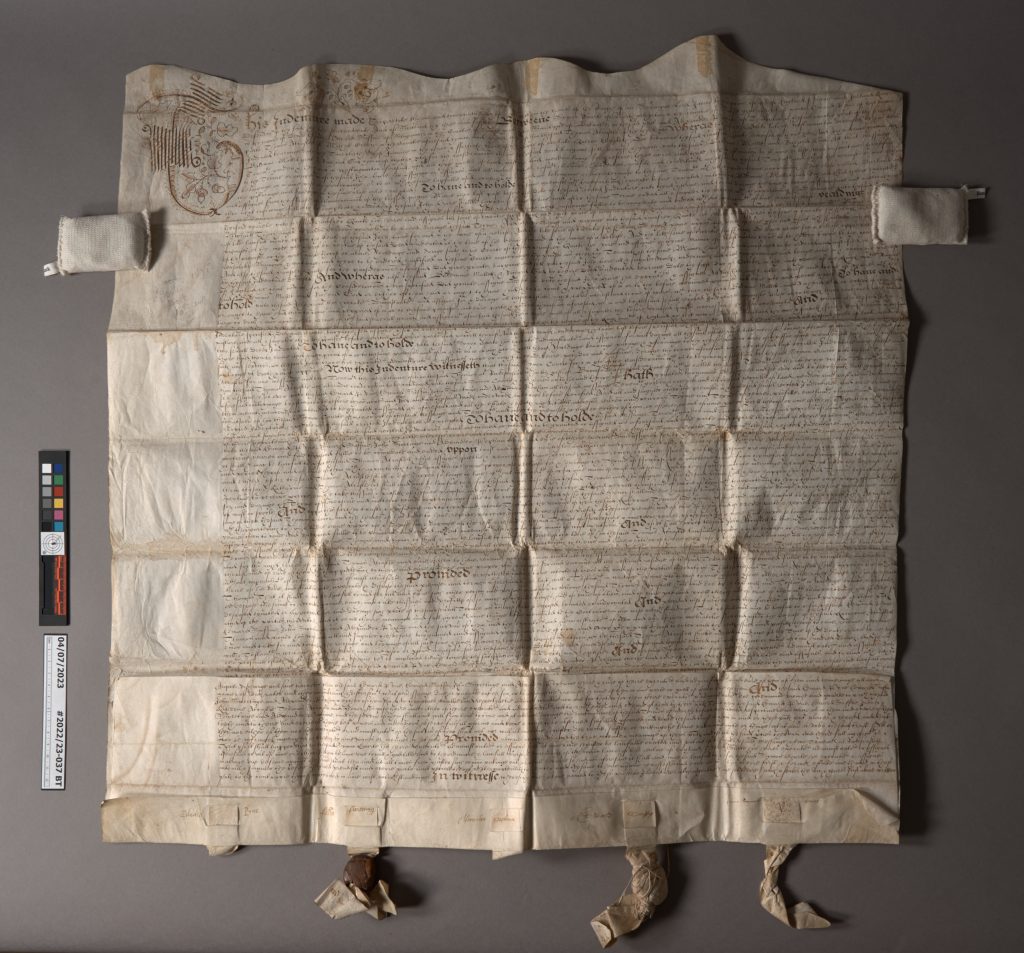

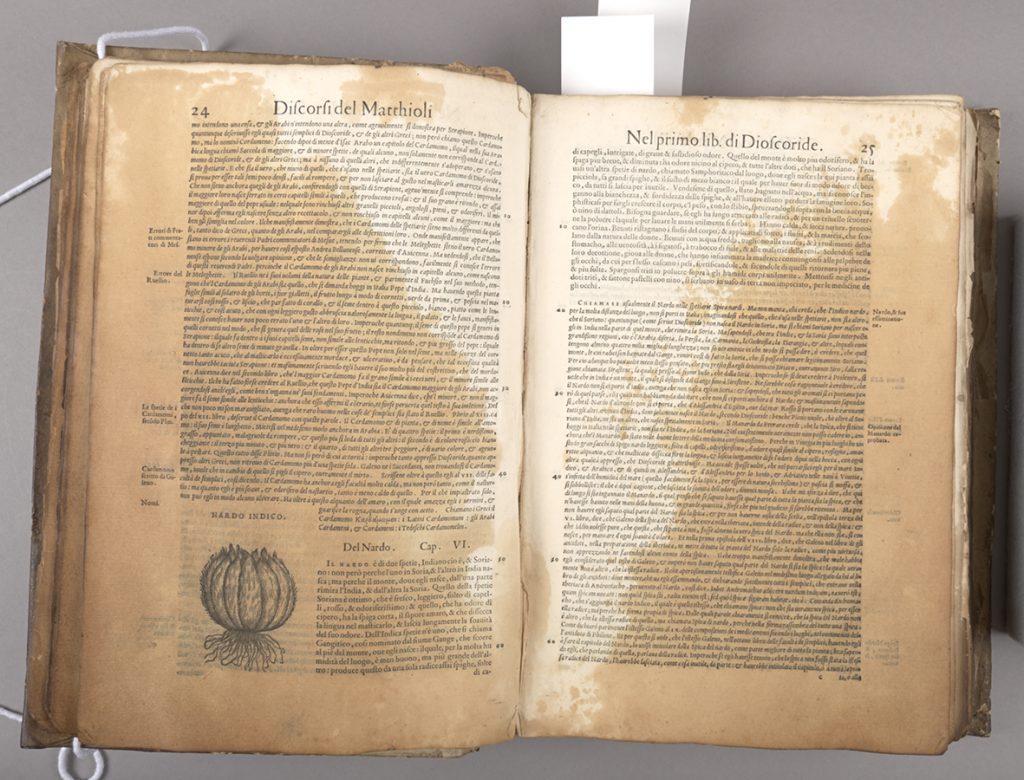

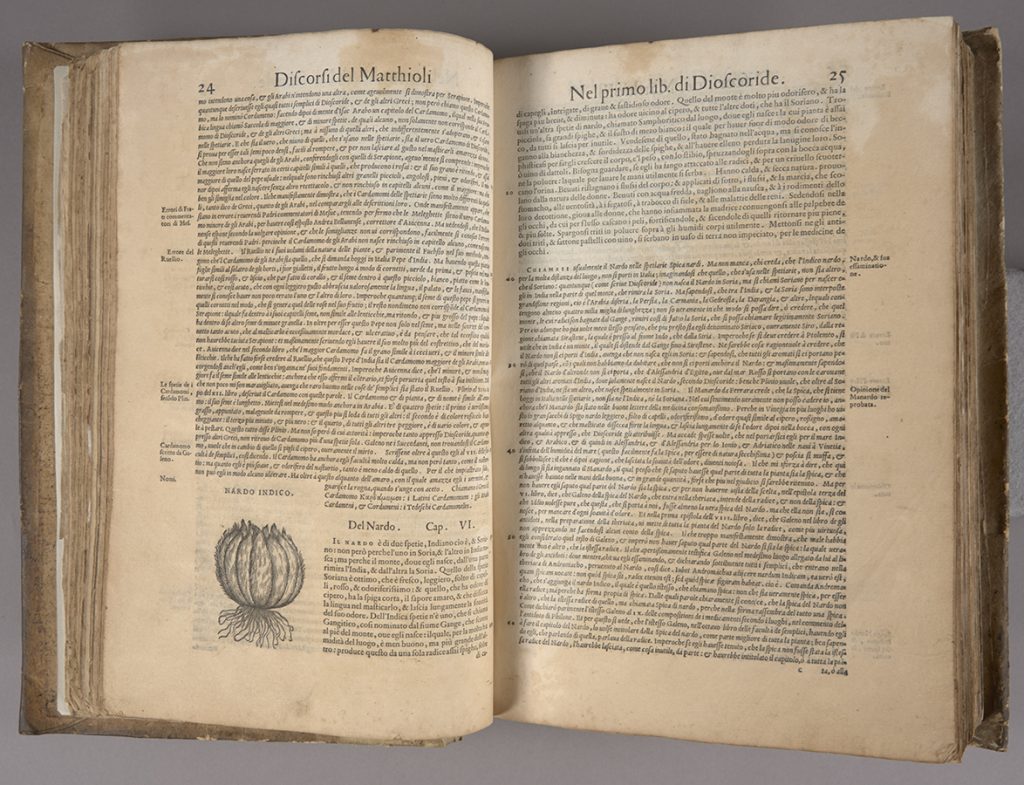

When we acquired it, about one quarter of the text and a portion of the early paper binding had long been saturated with oil, and there was less severe oil staining throughout. It was so soaked with oil that the pages were slightly transparentized and were becoming stiff and blocking together. This video demonstrates the condition and handling challenges it presented when we first received it [SOUND ON].

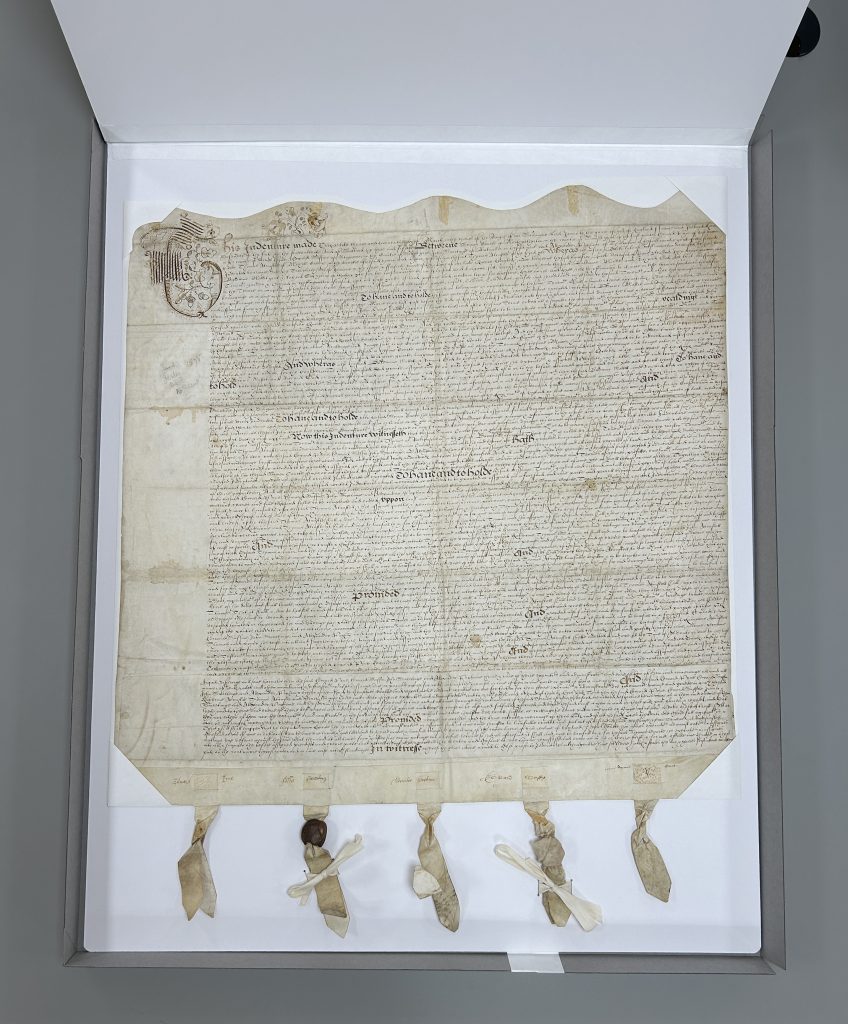

The text was bound in an early paper binding with a parchment spine overlay. The sewing was broken in places and pages were coming loose. Initial testing found that the oil was soluble in a couple of different solvents but I found that of the few I tested, ethanol moved only the oil but not the printing ink. With this information and considering other factors, the curators and I agreed that it was appropriate to disbind the text and to use solvent baths to remove as much of the oil from the paper as possible.

Working in our fume hood, I treated the most oil-stained sections of the text with multiple ethanol baths, which significantly drew out oily residues and moderately reduced the staining, a result that the curators were ultimately pretty happy with. These solvent baths were followed by water baths and then resizing, since the previous immersions removed most of the original sizing.

Saving some of the residual oil in ethanol, I was able to analyze it with Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) at the SMIF facility on campus. Conservation scientists in at the Winterthur Museum in Delaware were able to identify the residue as palm oil, along with an unknown plasticizer. These results ultimately didn’t impact the conservation treatment, but the information does present another interesting detail in understanding the curious life of this item. After treating the text, I mended it and resewed it, and was able to rebind it in the original binding.

I Discorsi… is likely to be on display in an upcoming exhibit on early botanical texts. You can also see further images and details of this treatment in the CDA, here. Many thanks to Dr. Mark Walters, Dr. Chris Petersen, and Dr. Jocelyn Alcantara-Garcia for their assistance in oil analysis and identification.