This month on the 1091 Project we discuss an essential part of almost every conservation department, student technicians. Without our students we could not keep up with the sheer amount of materials that come to the lab. This week is spring break, so I can’t show you pictures of our wonderful students, KellyNoel, Kaiti and Jessica (on loan from ERSM for a project), but I can tell you about the work they do and what we look for in a good student assistant.

This month on the 1091 Project we discuss an essential part of almost every conservation department, student technicians. Without our students we could not keep up with the sheer amount of materials that come to the lab. This week is spring break, so I can’t show you pictures of our wonderful students, KellyNoel, Kaiti and Jessica (on loan from ERSM for a project), but I can tell you about the work they do and what we look for in a good student assistant.

Student Workflows

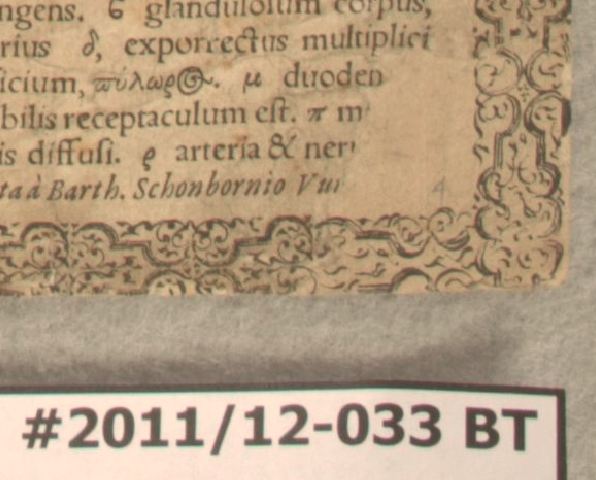

Our students start out learning how to bind pamphlets, make simple enclosures, create CoLibri book jackets, make pockets and do simple repairs such as tip ins, cut pages, and binding musical scores. They also help with the tracking and physical moving of materials.

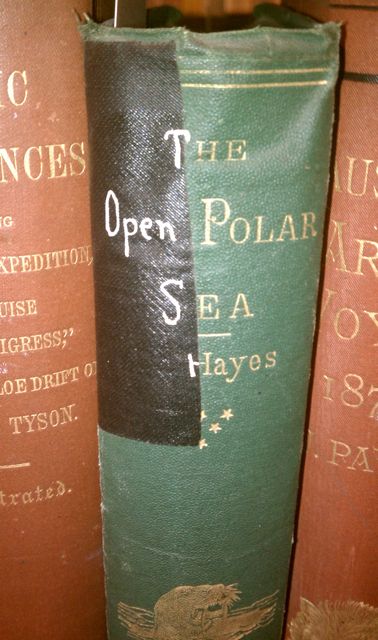

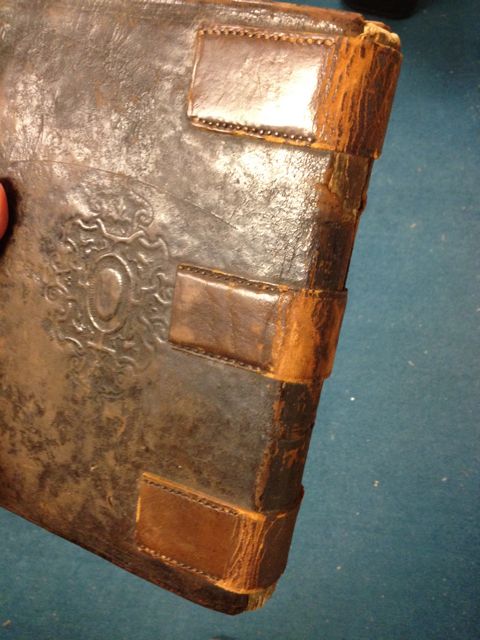

If the students have the abilities and interest they can learn more complicated repairs and enclosures. These might include recasing or rebacking books, or making four-flap or corrugated clamshell boxes for fragile materials. We have had a couple students who stayed for several semesters and because they had the skills and interest, they were able to learn multiple conservation rebinding techniques and cloth-covered clamshell boxes.

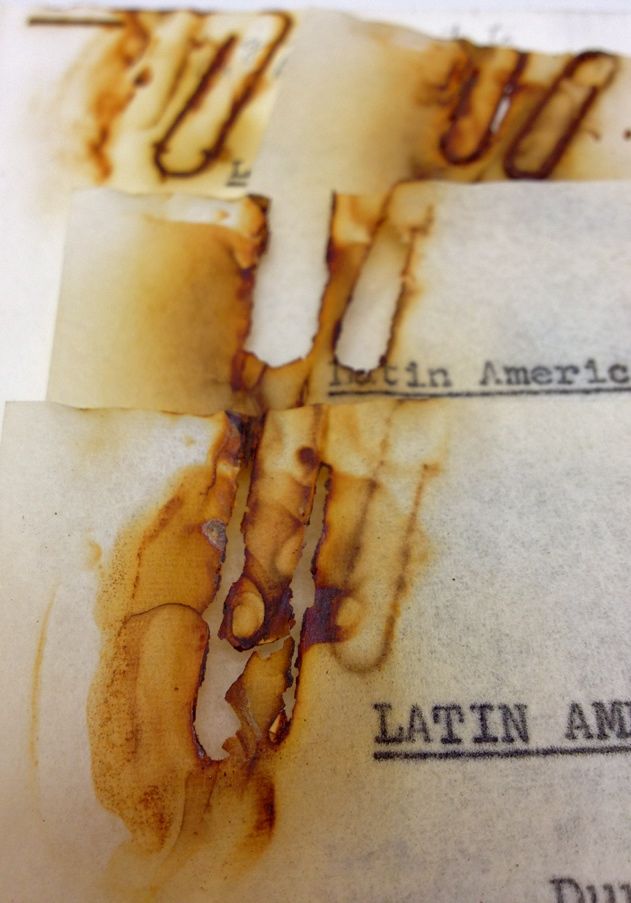

We currently have students helping specifically with renovation projects. These students are primarily getting the newspapers ready to go to the Library Service Center. This involves jogging brittle paper into place, fitting the bindings into pre-made boxes, and making spacers in the boxes so the brittle papers don’t shift around during transit. This is a very labor intensive, dirty and repetitive project but all of our students are working hard to meet our fast approaching deadline.

What We Look When Hiring Student Technicians

Most of our students are undergraduates, but every now and then we hire a graduate student. We of course like it if they have state or federal work study, but that isn’t a requirement. We prefer to get the right student with the right skills regardless of their funding. Occasionally we will get a UNC-SILS student who wants to intern with the department and we will work with them to develop a project that fulfills their school requirements but also helps us move our department forward.

There are basic job requirements that are listed in all of our positions including being able to use sharp instruments and large binding equipment safely, lifting heavy boxes and moving full book trucks, and being able to work in a potentially dusty or moldy environment.

Beyond that, what I look for when I interview students is the ability to learn quickly and be productive, to work independently but to know when to ask questions, and to have a good attitude and work well with a diverse staff. It is rare that we find students who have bookbinding experience, so I look for interests or past work history that involve eye-hand coordination and attention to detail. It might surprise you that gamers have very good eye-hand coordination, students with musical backgrounds are excellent at following instructions, and research science students are amazingly skilled at detail-oriented work. If you are a student, you don’t need to be a crafty person or an art major to work here. We can teach you the skills you need to be successful if you have the ability to learn the craft.

Let’s head over to Parks Library Preservation to read about their students.