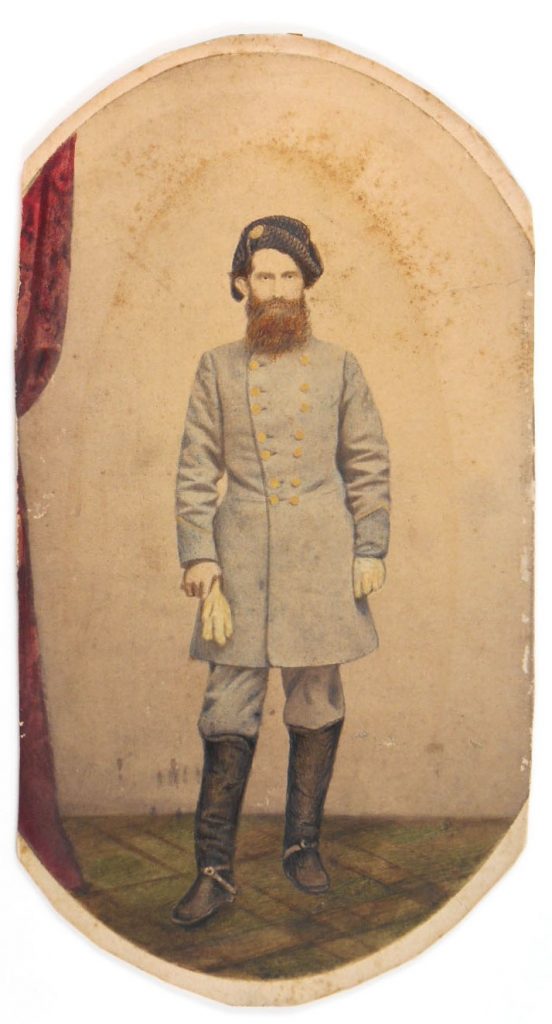

One of my more recent projects has been working on this gorgeous late 19th century Japanese photograph album.

While I’m still dealing with the album itself, today I’d like to briefly share some steps I’ve taken to stabilize the decorative paper box in which the album was originally purchased and stored. When the album came to the library, it was inside the original enclosure, and both album and enclosure were packed in a regular cardboard box with medical underpads as cushioning material. Unsure of what I was really looking at, I documented the object exactly as it came out of the cardboard box – underpads included!

The underpads do have some merits as packing material, providing both cushioning and a moisture barrier. They are not the best long-term storage materials, though, so we opted to remove them. As you can see, the box was looking a little rough. I removed the photo album and laid out each piece of the enclosure to better see what remained.

The enclosure is essentially a drop-spine box, covered in decorative red and gold paper. Yellow textile pads are included in the interior of the lid and base to protect the lacquer and ivory covers. The head, tail, and fore-edge of the lid have black woven textile straps and bone pins, which originally fastened to small woven textile loops laced through the lower tray walls. As you can see, several parts of the box are missing and most of the joints have broken. The straps are also broken in several places and very weak.

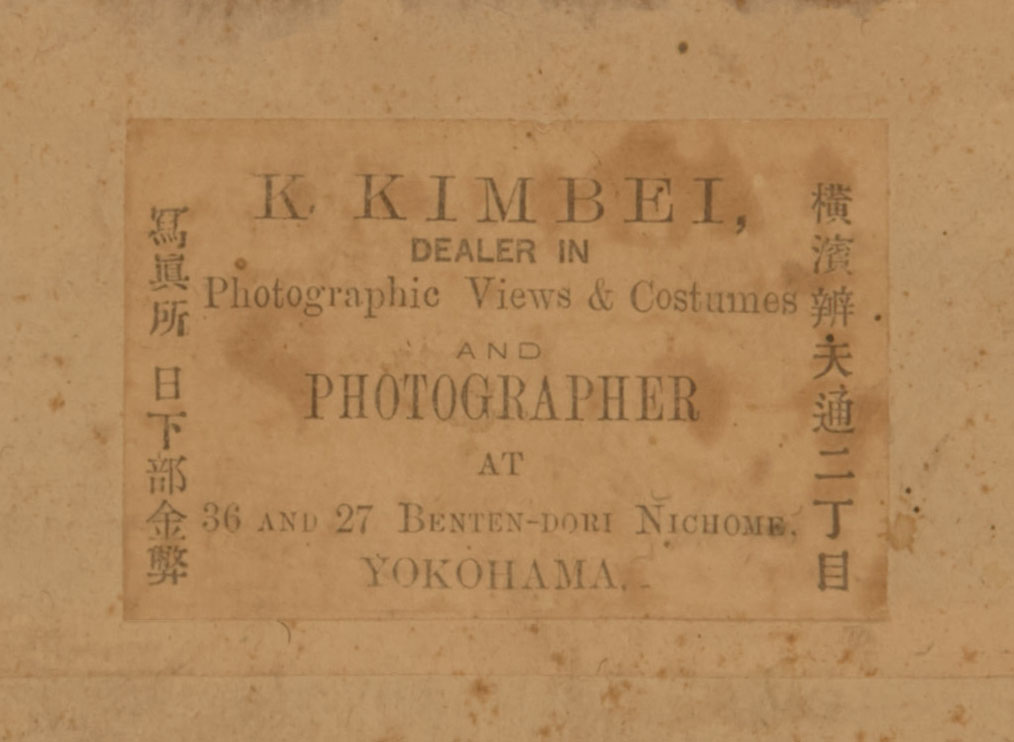

This enclosure is special because it includes a great deal of information about the album’s provenance. Kusakabe Kimbei (1841-1932) is widely known for these souvenir albums, consisting of hand-colored portraiture and scenic views. Bennet (2006) describes Kusakabe’s (1841-1932) businesses at the two Benten-Dori addresses: 36 functioned as a photography studio, while 27 operated as a shop where composite albums of Kusakabe’s prints were sold (p. 135).

We want to ensure that researchers can open and closely examine the enclosure to see the information on the interior label, but it is not necessary for the heavy photo album to remain inside. The decision was made to create a new padded enclosure for the album and stabilize and store the original enclosure separately.

I began by re-assembling all the box pieces in much the same way I might repair the joints of a paper binding. Using the patterns on the decorative paper, I was able to match all the detached pieces. The original decorative paper was lifted away from the boards and strong handmade paper, toned to match, was adhered underneath with wheat starch paste. I stabilized the remains of the textile straps using toned 60/3 linen thread.

Since the enclosure will not contain the heavy album anymore, the decision was made to just reattach and stabilize the extant materials, rather than recreating the lost walls of the tray and edges of the lid with new board. With only two walls on the bottom tray, I decided to construct a small corrugated box to fit inside and act as additional support. The “filler” box is light weight and can easily be removed by a researcher. This set of two boxes will get a final, outer box to protect the textile straps.

A box, within a box, within a box.

Bennett, T. (2006). Old Japanese photographs: Collector’s data guide. London: Quaritch.