Post contributed by Brooke Guthrie, Research Services Librarian and Rachel Ingold, Curator, History of Medicine Collections.

Philadelphia in 1793. New York in 1795. Gloucestershire in 1798. London in 1854. Crimean Peninsula in 1855.

This may seem like an unrelated list of places and dates, but each represents a particular moment in the history of our fight against infectious disease. From the earliest days of epidemiology to the experiments that launched our vaccinated world, these moments continue to resonate today. While most of us have more immediate concerns – from job security to our own physical and mental health – it is worth considering the roots of now-common disease maps or the idea of “social distancing” to slow infection rates.

The Rubenstein Library’s History of Medicine Collections has material related to the history of epidemics, pandemics, and infectious disease. Below you’ll find a sample of sources from us as well as resources from other institutions.

Yellow Fever, 1790s

When yellow fever struck Philadelphia in 1793, nearly a tenth of the city’s population perished during the outbreak. Physicians struggled to understand how the disease spread and struggled to effectively treat the growing number of ill Philadelphians. One physician, Benjamin Rush, wrote to his wife throughout the outbreak and their letters offer a look at life during an epidemic.

These letters, part of the Benjamin and Julia Stockton Rush papers, are digitized and available online. A companion digital exhibit, Malignant Fever, curated by Mandy Cooper, provides more information about Rush and includes additional resources for understanding the 1793 outbreak.

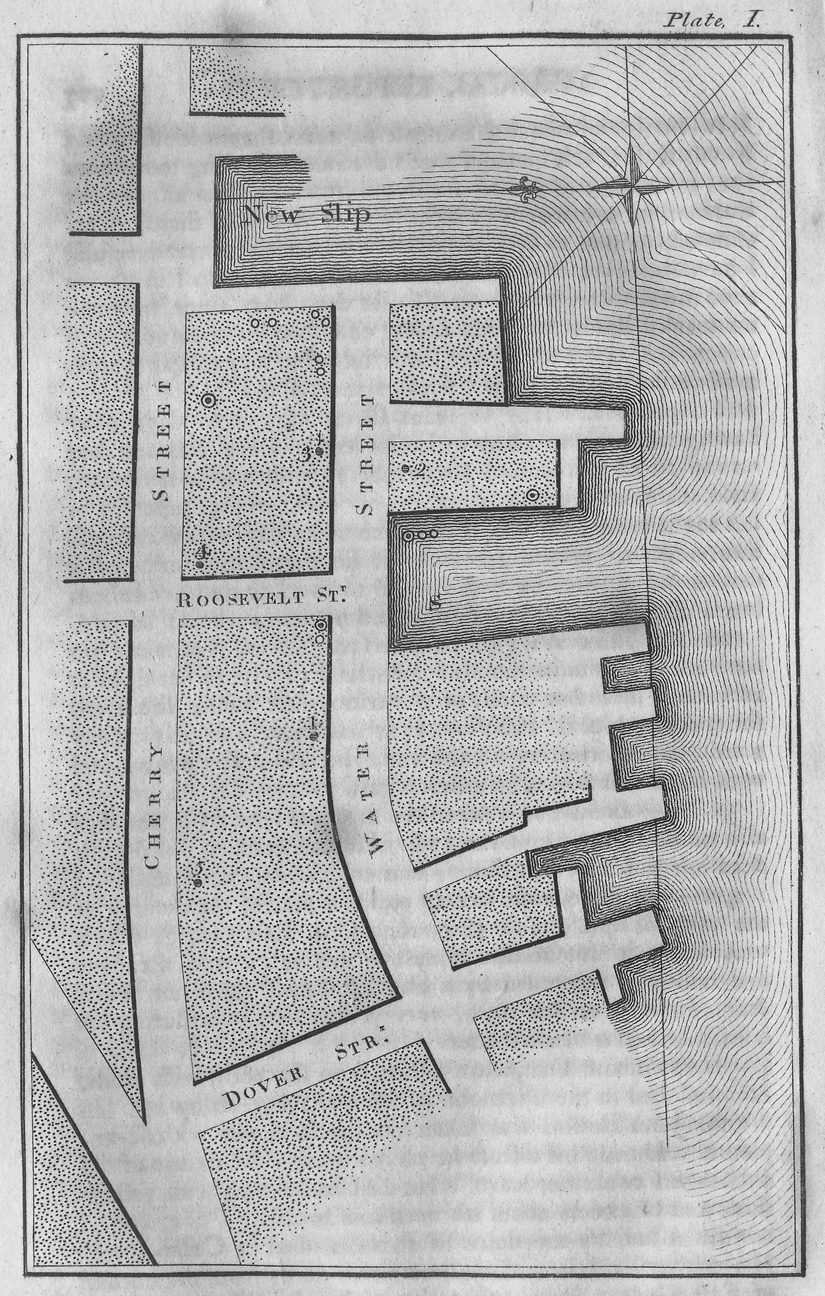

Other American cities were not immune to yellow fever and New York City saw an outbreak in 1795. Local physician Valentine Seamen, trying to locate the source of the disease, collected information about each case and created an early disease map using this data.

Seaman, despite his efforts, did not correctly identify the cause of yellow fever. He did note the presence of mosquitoes, but concluded that the accumulated filth near the city’s docks were to blame. Seaman’s case data, maps, and his analysis were published in The Medical Repository. The Rubenstein Library has a copy and a digitized version can be accessed through HathiTrust.

Cholera, London, 1854

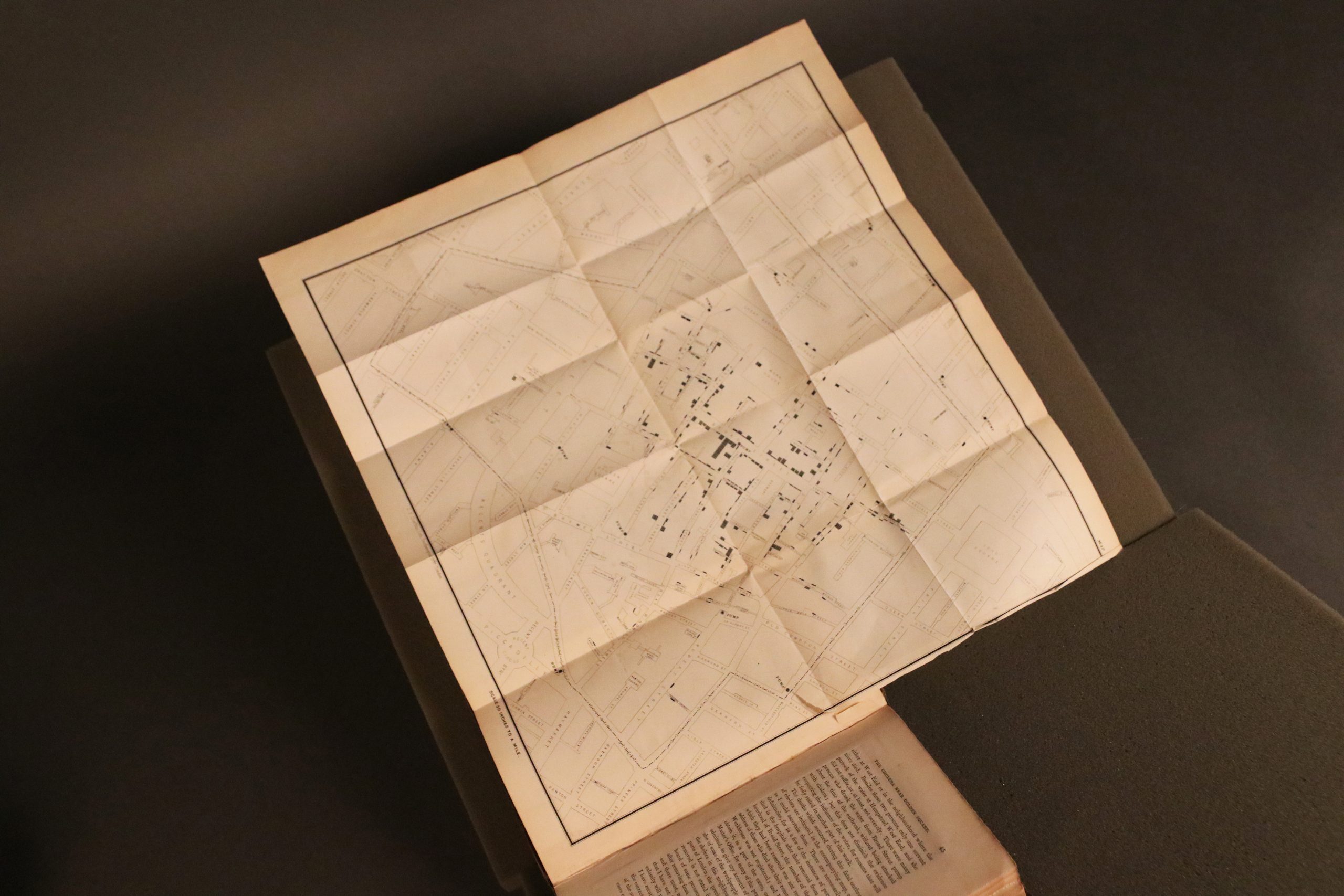

A later attempt to trace the source of a contagion through mapping was more successful. John Snow suspected that contaminated water was to blame for a cholera outbreak in London. Snow investigated each case and noted which water pump the infected individual used. He marked the cases on a map published in the 1855 edition of On the mode of communication of cholera.

Fortunately, Snow was right about the source of cholera. His data was convincing enough to have the water pump at the center of the outbreak disabled. The Rubenstein Library holds a rare copy of On the mode of communication of cholera (shown above).

Smallpox, 1790s

Decades before John Snow’s map, Edward Jenner investigated smallpox, a widespread and dangerous disease in the eighteenth century. Jenner created an early vaccine using material taken from a fresh cowpox lesion after observing that cowpox infection prevented subsequent smallpox infection. Jenner shared his discovery in An Inquiry into the causes and effects of the variolae vaccinae (1798). The library holds a copy of this book containing surprisingly lovely illustrations of infected arms. The library also holds a small collection of Edward Jenner’s papers that include letters discussing vaccination and a diary containing vaccination records.

Camp Diseases, Crimean Peninsula, 1854-1855

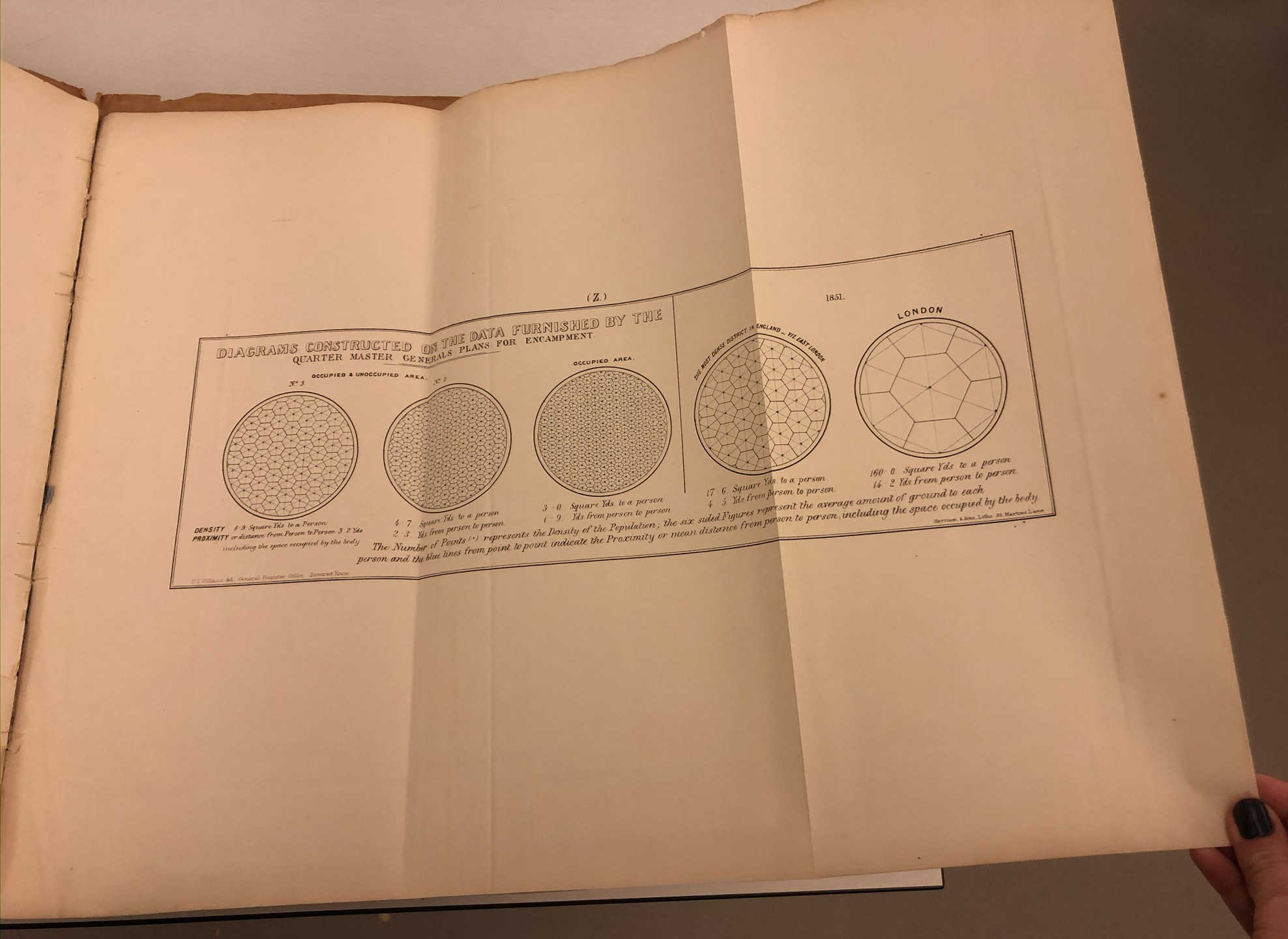

As a nurse during the Crimean War, Florence Nightingale saw large numbers of soldiers die from diseases like cholera, dysentery, tuberculosis, and typhus. Linking these deaths to poor sanitation, Nightingale worked to clean up military camps while also collecting data about the impact of disease on British soldiers.

In Mortality of the British Army (1858), Nightingale’s data is used to create visualizations that illustrate the poor camp conditions and make the case for sanitation reform. One visualization stands out as we practice “social distancing.” The image below compares the population densities in various locations and notes the amount of space per person. Densities in military camps, where disease was widespread, were noticeably higher than even places like urban London where people had more distance from their neighbors.

We hold a copy of this work (that is definitely worth seeing in person) and a digital copy is available through Internet Archive.

From our colleagues at other institutions, you can find other excellent resources on this topic:

Contagion: Historical Views of Diseases and Epidemics is a digital collection of sources from Harvard libraries. As their site explains, the goal is to provide historical context to current epidemiology and contribute to the understanding of the global, social-history, and public policy implications of disease. Materials include digitized books, manuscripts, pamphlets, and more. The site is organized around momentous historical outbreaks such as the 1793 Yellow Fever epidemic in Philadelphia and the 1918 Influenza outbreak in North America.

The National Library of Medicine and National Institute of Health also have a number of resources, such as health information guides from past pandemics. The National Library of Medicine hosts the Global Health Events web archive, a resource that has archived selected websites from 2014 around major global health events such as Ebola and Zika. The collection includes both websites and social media with the goal of offering a diverse and global perspective ranging from government and NGOs to healthcare workers and journalists.

This is by no means an exhaustive list of resources related to infectious disease and the attempts to stop its spread. If you want to explore more of these materials in the Rubenstein or find additional online resources, our “Guide to Researching Epidemics in the Rubenstein” is a good place to get started.

We encourage you to visit us when we reopen to the public! In the meantime, get in touch and let us know if you have questions!