During the process of treating items from the collection, we sometimes discover interesting details about their production that can be useful for researchers. Take, for example, this repair that I completed last year on The Byrth of Mankinde, a book printed in London in 1545.

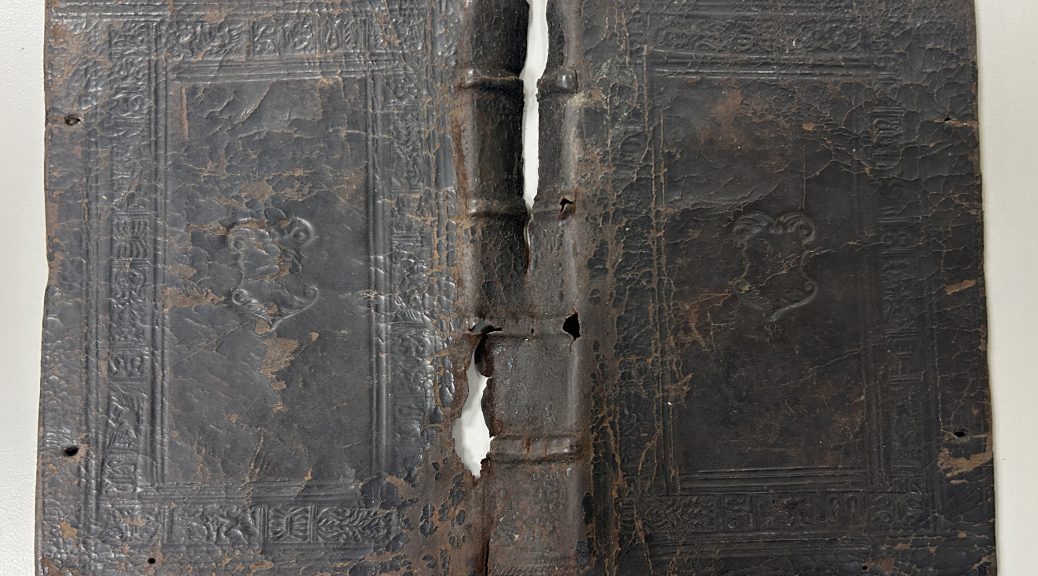

It came into the lab because the front board was detached from the textblock and the leather was split along the spine. We were concerned about further damage occurring to some of those original binding materials with use in this condition, so it was important to reattach the front board and adhere the lifting leather.

It came into the lab because the front board was detached from the textblock and the leather was split along the spine. We were concerned about further damage occurring to some of those original binding materials with use in this condition, so it was important to reattach the front board and adhere the lifting leather.

The textblock is printed on paper, but on the right side of the image above, you can see the smallest sliver of manuscript on parchment. It was common for binders to use waste material in the construction of bindings. Parchment is a very strong material that can be used to reinforce the board attachment of a book, so it was a common practice to cut up the leaves of parchment manuscripts and paste the fragments into new bindings.

It turns out that all of the adhesive attaching the leather to the boards had completely dried out and failed, so during treatment I was able to just slide it off of the book – kind of like a glove. You can see the major splits through the head of the spine and some sizable losses where the raised bands lace into the boards. At one point the binding had green silk ribbon fore-edge ties protruding from the front and back boards, but they have since broken off and only fragments remained adhered under the pastedowns.

It turns out that all of the adhesive attaching the leather to the boards had completely dried out and failed, so during treatment I was able to just slide it off of the book – kind of like a glove. You can see the major splits through the head of the spine and some sizable losses where the raised bands lace into the boards. At one point the binding had green silk ribbon fore-edge ties protruding from the front and back boards, but they have since broken off and only fragments remained adhered under the pastedowns.

With the leather off of the book, I had more access to view the structure of the binding. The sewing supports are made from tanned leather, which do not remain as flexible as they age. It is not surprising that they have failed. Above you can see the manuscript fragment stub wrapping around the last section of the textblock.

In addition to the failing adhesive, the sewing also broken in the first section, so I was able to release the parchment fragment from the interior of the front board and photograph both sides of it. These photos will be available to researchers when they are ingested into the Conservation Documentation Archive later this year. The text on the manuscript might provide more information about the provenance or production of this book.

I used linen thread to create new sewing supports over the front joint and sewed the first section, with it’s parchment fragment, back onto the textblock. After reattaching the front board and readhering the original leather (with some toned Japanese paper lining the interior of the spine), I decided to leave the parchment fragments loose from the boards at the front and back. Should anyone be interested in reading the text on those fragments, it will be easy to access them if they aren’t hidden under the original pastedowns. I made new pastedowns from handmade paper, so now the original pastedown just becomes the first leaf of the book. This changes the initial experience of reading the book, but from the staining and presence of bookplates, it’s pretty obvious that the now free leaf was once pasted down.

See our other Preservation Week 2025 posts here:

Day 1: Curatorial meetings

Day 2: Presenting our HVAC pilot project

Day 3: Using UV light to analyze materials

Day 4: Discovering details in book bindings

Day 5: Field trip! Gathering damaged books from Circulation points