On March 20, 2020, the Duke University Libraries were closed related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Surrounded by a great deal of uncertainty as to when the Libraries would reopen, most library staff were sent home to work for the next months from home. During this time, the Digital Production Center’s employees followed suit and, as part of that time away from the DPC, completed post-processing of images, image quality control, participated in project planning and wrote blogs on the closing of the Libraries, labor in the time of the coronavirus, and the history of videotelephony. Following the end of the North Carolina Stay-at-Home order on April 29, discussions began in earnest about what the new reality would be for the Libraries. It was determined that the DPC’s unique skill set was needed on site sooner rather than later, and so on June 26, we returned to Duke’s campus as “essential workers.”

Upon our return, we needed to make sure that our equipment was sanitized and in good working order. Along with testing our scanner and cameras, we also recalibrated our monitors to ensure color accuracy and established our new workflow.

It was determined that our efforts were most needed to prepare for Duke’s fall instruction materials. With the uncertainty as to whether or not classes would be held in person or virtually, preparing digital materials to work with was prioritized. So, we shifted from our normal project work to focus solely on digitization of these materials. Each digitization specialist was asked to be onsite for 3 days a week to maximize use of our capture equipment. The remaining two days of the week would be spent working from home to do quality control work on the images as well as various administrative tasks. We had a plan; our remit was clear and we were working towards a goal.

On August 17, classes began for Duke University and our images began being used as part of instruction materials. Duke University Library’s digitized images helped bridge the gap between the currently inaccessible library collections that Duke faculty and students normally rely on for coursework and the Fall 2020 students.

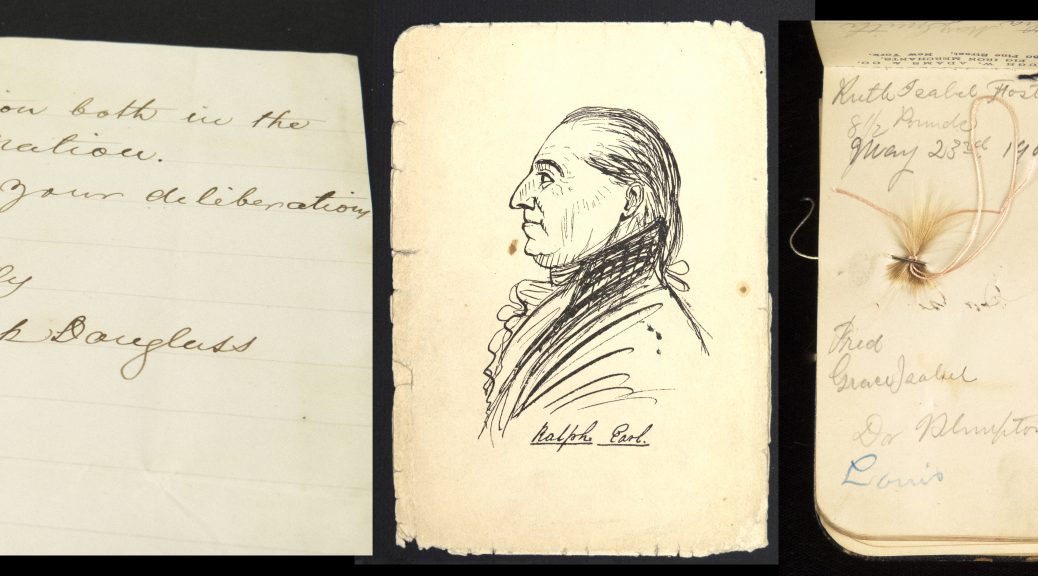

Thinking about the change in use and accessibility for collection materials leads to an interesting question: With the lockdown which happened for most of the US, did digital collections receive more visits as people were restricted from leaving home and libraries were closed? A quick glance at the Google Analytics for the Duke Digital Collections shows a 34% increase of unique page views from April 1-June 30 of this year as compared to the same time period in 2019. While it is impossible to state definitively why the increase occurred, the pandemic is very likely a contributing factor. Digital collections are arguably valuable assets for any institution which supports them. They provide easy access to rarely seen or inaccessible materials and they have the potential to incite curiosity in the larger institutional holdings. It is indeed interesting to consider what types of innovative scholarship and creative use of digital content may result from the pandemic’s “forced” use of digital collections over the next twelve months.

Of course, the rapid onset of the COVID-19 pandemic illuminated the need for alternative ways of operating. At least temporarily, it has changed the way in which the Duke University Libraries are conducting business as usual these days. And, in July of this year, Research Libraries UK published a document entitled “COVID19 and the Digital Shift in Action.” This document reports on the effect of the pandemic on UK research libraries and suggests strategies for emphasis and support of the digital aspects of libraries as well as the need for change and flexibility within library collections. Digital collections, e-books, e-textbooks, and digital content had their moment to shine during the pandemic and they have proven their value and importance.

And with the potential increased reliance on digitized material, many cultural heritage digitization specialists are now back on site in libraries, museums and archives, working to provide their expertise to add to existing digital collections. Naturally, at the Duke Digital Production Center, we have been asked a number of times since our return if we are nervous about being back in our studio space. Of course, we are, but we also recognize how our skills and contributions continue to create value for Duke University and Duke University Libraries.

Further reading:

Biswas, P., & Marchesoni, J. “Analyzing Digital Collections Entrances: What Gets Used and Why It Matters.” Information Technology and Libraries, v. 35, n. 4, p. 19-34, 30 December 2016.

Greenhall, M. “Covid-19 and the digital shift in action,” RLUK Report. 2020. Can be accessed at: https://www.rluk.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Covid19-and-the-digital-shift-in-action-report-FINAL.pdf

Markin, Pablo. “Pandemic Restrictions on Library Borrowing Showcase the Importance of Digital Collections and the Advantages of Open Access.” Open Research Community. 11 August 2020. https://openresearch.community/posts/pandemic-restrictions-on-library-borrowing-showcase-the-importance-of-digital-collections-and-the-advantages-of-open-access