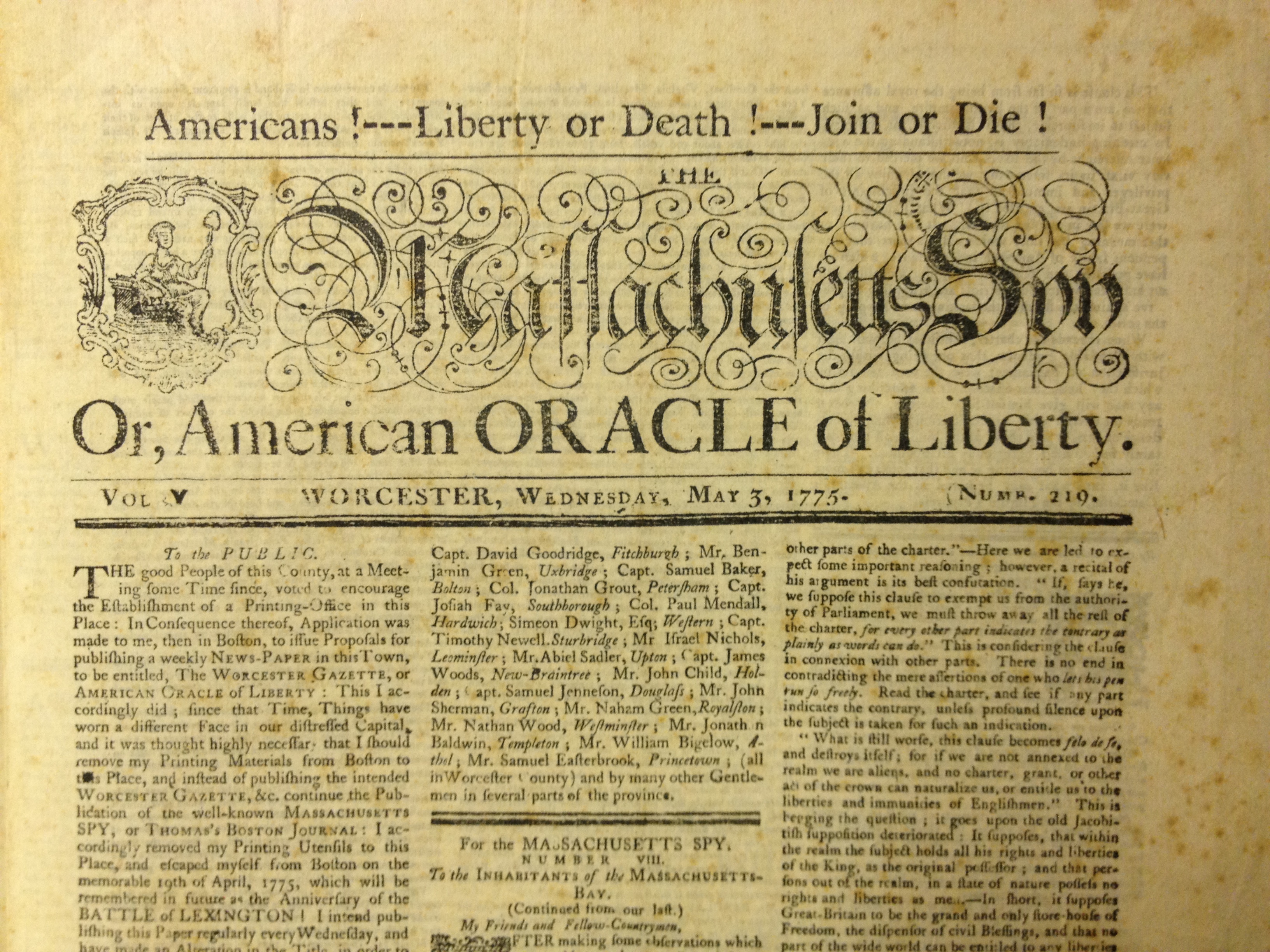

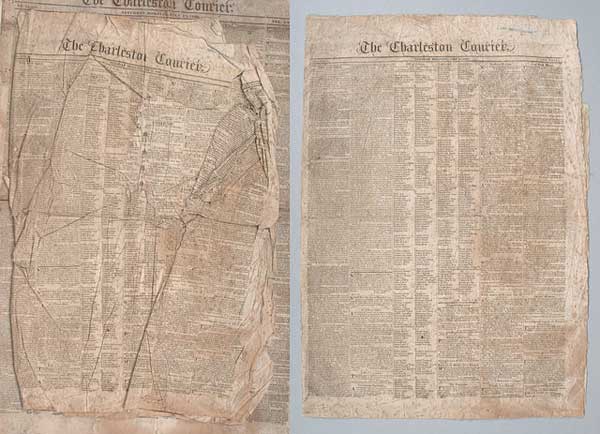

My most recent project in the conservation lab has been a set of 32 newspapers, issues of the Charleston Courier from 1815 to 1851. Some time in the past, they had been damaged by water, mold, insects, and dirt. All of them had tears, and many also had large losses and were exceedingly fragile. When they arrived in the lab, I could tell immediately that they were going to require a lot of work, but that they would also be fun and rewarding. While modern newspapers are made of wood pulp which quickly degrades, turning brittle and yellow, old newspapers were printed on rag paper made from textile fibers like cotton and linen, and thus they are much more resilient and pleasant for a conservator to work with.

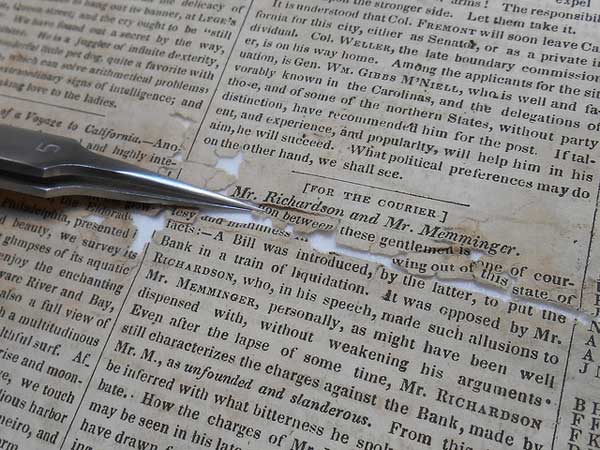

I knew I would need to do aqueous treatments, so, after cleaning off the surface dirt, I tested the inks to make sure they would not be soluble in water. While the black printing ink was stable, most of the papers had a collection stamp in turquoise ink that was sensitive to water. However, I was able to find three ionic fixatives, chemicals that are used to make certain dyes insoluble. I tested all three, and one (Mesitol NBS) turned out to be exactly what this ink needed. I used a brush to apply a small amount to the blue inked area, working over the suction platen to pull the chemical all the way through the paper, and then my newspapers were ready to wash.

Each newspaper was immersed in a bath of deionized water. Extensive discoloration and degradation products were washed out, turning the water peachy yellow. I changed the water in each tray until it stayed clear, signaling that washing was complete. It was rewarding to see what a visual and physical difference there was between the washed and unwashed papers.

After washing and drying, I had many hours of mending to do, and many little puzzle pieces of newspaper to put in place. For my mends I used wheat starch paste and very thin Japanese papers which are almost transparent so as not to obscure the text on the newspapers. I did not fill all of the numerous losses, but I made the newspapers more stable for researchers to handle.

While working on the repairs, I was often confronted with fragments that would say something like “General / troops / fired” on one side and “congress / voted / article” on the back, and thus I would find myself reading the papers to know where the pieces might belong, which is something I rarely get the chance to do beyond a quick perusal. The earlier newspapers had battle reports, as the war of 1812 was still going on. The articles were fascinating, and the advertisements even more so. Many were similar to modern ads: houses for rent, job postings, theater listings, lost and found, dubious medical cure-alls, and sales of merchandise, often accompanied by decorative printed icons. Some were a little more unusual and interesting, like an ad for “Daguerreotype Paintings” or a woman offering her service as a wet nurse. But I was surprised to see ads for slaves, either for sale or wanting to buy, and many alerts for runaways. The runaways were the most intriguing as they gave personal details of the individuals, and I found myself wondering what happened to them, applauding their escape and hoping that they found a better life.

When the mending was finished, I housed each of the newspapers in a clear Mylar sleeve so they can be handled with greater ease and safety. Even after treatment many of them are still fragile, but now they can be handled and used by researchers with much less risk of damage. And I hope they will be used, as they are fascinating! To see more images of treatment and examples of interesting advertisements, see our Flickr page.

Post contributed by Grace White, Conservator for Special Collections, as part of our ongoing “In the Conservation Lab” series.