Join us Wednesday, November 18th for a talk by John Gartrell, Director of the John Hope Franklin Research Center.

I – Illinois (Chicago)

John Hope Franklin and his wife Aurelia lived in the state of Illinois, specifically in Chicago, for several years. In 1964, Franklin joined the faculty at the University of Chicago, where he served as Chair of the History Department from 1967-1970, and was the John Matthews Manly Distinguished Service Professor from 1969-1982, he became Professor Emeritus in 1982.

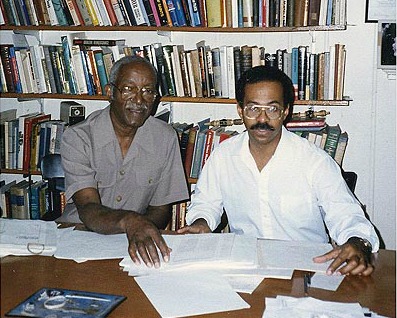

During his tenure at the University of Chicago, Franklin published Color and Race (1969), and Illustrated History of Black Americans (1970), Racial Equality in America and Southern Odyssey: Travelers in the Antebellum North (1976). Franklin also served as advisor to over twenty PhD graduates from the department of history, including noted scholars Genna Rae McNeil, Paul Finkelman, Juliet E.K. Walker, Loren Schweninger, and Alfred Moss.

Franklin was also entrenched in the community, working on boards and committees of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, Chicago Public Library, Chicago Urban League and NAACP, and DuSable Museum.

In 1984, four years after John Hope Franklin moved back to Durham, NC, Franklin received the Illinois Humanities Council Public Humanities Award. This annual award is presented to an organization or an individual who has made significant contributions to the civic and cultural life of the State of Illinois through the humanities.

This series is a part of Duke University’s John Hope Franklin@100: Scholar, Activist, Citizen year-long celebration of the life and legacy of Dr. John Hope Franklin

Submitted by Gloria Ayee, Franklin Research Center Intern

We are wrapping up processing on the John Hope Franklin Papers — more on that soon! — but I couldn’t let this project end without sharing a bit of its lighter side. Newspaper drawings and cartoons of Franklin popped up throughout processing, often having been clipped and sent to Franklin by his friends and admirers. Here is a case where we see Franklin’s reaction to one of his cartoons, shared with him by a friend in Raleigh.

The sketch in question appears to have been published as part of a syndicated comic strip in newspapers around the country.

Here is Franklin’s response:

“It is not the best drawing I have seen of myself, but I don’t complain.” Understatement of the year, maybe? Franklin’s friendly good humor is prevalent throughout his papers, which has made them particularly enjoyable to process over the past year. Stay tuned for more information about the conclusion of the Franklin Papers processing project.

Post contributed by Meghan Lyon, Technical Services Archivist.

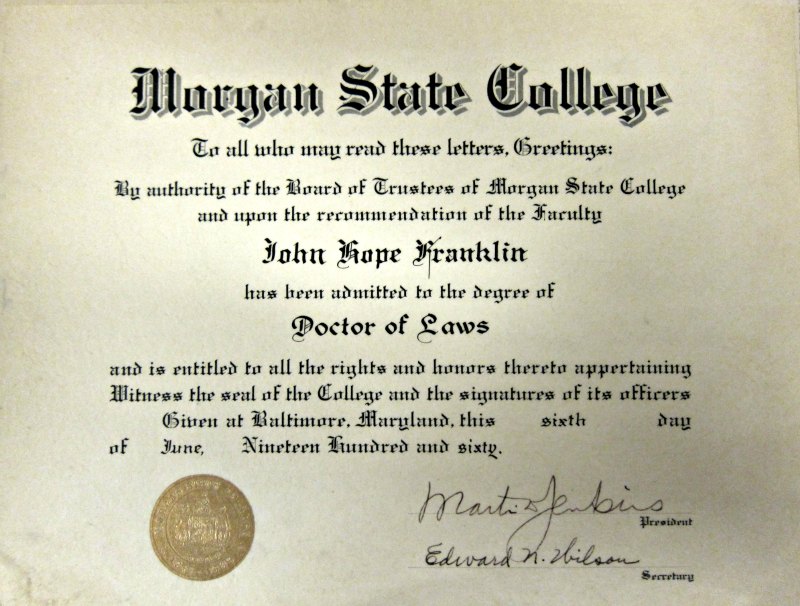

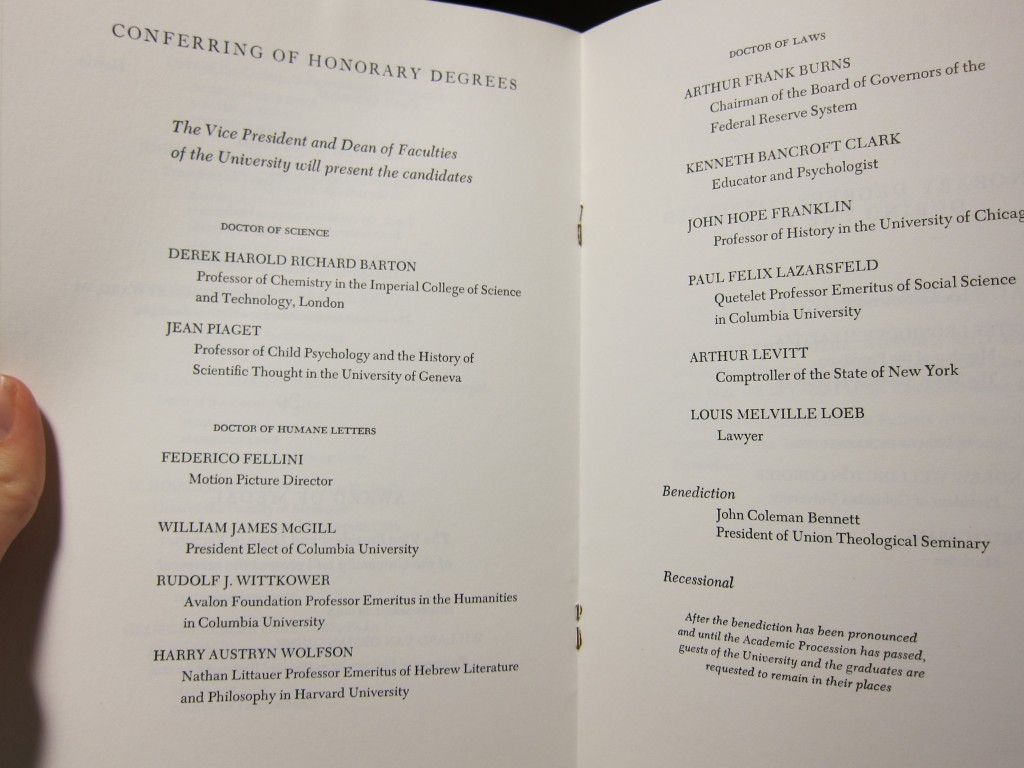

One of the most interesting batch of records I’ve worked with in the ongoing processing of the John Hope Franklin Papers are the Honorary Degrees, a subseries of Franklin’s Honors and Awards. In the course of his life, Franklin collected over 130 honorary degrees from colleges and universities all over the United States. Franklin appeared to cherish these awards, never turning one down unless it conflicted with a pre-existing engagement. By the 1970s and 1980s, Franklin’s weekends in May and June were booked — so booked that he would occasionally receive one degree on a Saturday, and another on a Sunday. Franklin also delivered the commencement addresses at many of these ceremonies, sometimes serving as the school’s first African American commencement speaker.

There is more to this series than a bunch of diplomas (although there are plenty of those, too). The pomp and circumstance occasionally overshadow the tense relationships between historically white university administrations and the growing numbers of African American faculty and students campaigning for civil rights in the United States. For example, before receiving his honorary degree at the University of Maryland (alongside Mary Poppins herself, Julie Andrews), Franklin was contacted by the campus’s Democratic Radical Union of Maryland and informed that the campus was still “effectively segregated” and under “virtual Marshall law.” The group of about 50 faculty urged him “not to help the administration at Maryland legitimize their power by taking part in one of their ceremonies on their terms, but rather to attend and stand with us against the political and racial repression that exists at this university” (telegram, June 3, 1970). Franklin went ahead with the ceremony, much to the frustration of the DRUM. He was the school’s first black honorary degree recipient.

Franklin’s honorary degrees also reveal the wide-sweeping connections he established over the course of his life in scholarship. Many of his early honorary degrees were from historically black colleges, allowing him to further engage with leaders of the civil rights movement. In 1960, Franklin delivered the commencement address at the Morgan State ceremony that honored both him and W.E.B. Du Bois with honorary degrees, shortly before Du Bois moved to Ghana. This was only one of several occasions when the two men interacted with each other. In 1961, Franklin received an honorary degree from Lincoln University at a commencement addressed by Martin Luther King, Jr. He later joined King on the march to Selma.

Later degrees attest to the random connections and coincidences of academic life. For example, at the Yale commencement in 1977, Franklin was honored alongside President Gerald Ford and musician B.B. King. He received his 1970 honorary degree from Columbia University with Arthur Burns, an economist and former chairman of the Federal Reserve whose papers are held at Duke. A 1984 ceremony at the University of Connecticut honored him alongside Marian Anderson, celebrated contralto.

I was curious how John Hope Franklin’s 130+ degrees compared to other honorary degree holders — so I did some online searching. Most people come nowhere close to Franklin. Sir David Attenborough, scientist and documentary filmmaker behind the epic Planet Earth series, holds the record in the United Kingdom for the most honorary degrees: 31. Maya Angelou, U.S. Poet Laureate and one of Franklin’s close friends, has also received over 30 honorary degrees. Two Nobel Peace Prize winners come closer to Franklin’s total: the Dalai Lama has received at least 70 honorary degrees, including two last month from the University of Maryland and Maitripa College. Another Nobel laureate, Elie Wiesel, cannot remember how many honorary degrees he’s received, but reckons they number over 100. But, lest you think we have a record-holder at the Rubenstein, Franklin’s degrees pale in comparison to Daisaku Ikeda, a Buddhist philosopher and educator who has received over 300 honorary degrees and professorships from universities and colleges around the world. One can only imagine what Ikeda’s weekends look like.

Post contributed by Meghan Lyon, Technical Services Archivist.

We are in the middle of processing the John Hope Franklin Papers, and it has been inspiring to see Franklin’s wide range of intellectual interests and community engagements. He was a very busy man! One recent discovery, mixed in with folded programs and family correspondence, is Franklin’s “Grownup School List,” an all-encompassing list he created of must-reads in African American history. Always a humble scholar, he omitted his own monumental works. We’ve reproduced the Grownup School List here, along with Franklin’s annotations. You can find all of these books, along with Franklin’s own extensive scholarship, online or in the Duke Libraries.

Post contributed by Meghan Lyon, Technical Services Archivist. This is the second in a series of posts on interesting documents in our collections to celebrate Black History Month.

We are pleased to announce a major addition to the John Hope Franklin Papers. This gift includes over 300 boxes of papers and other materials belonging to late historian and Duke professor John Hope Franklin.

Franklin is widely credited with transforming the study of American history through his scholarship, while helping to transform American society through his activism. He is best known for his ground-breaking history From Slavery to Freedom: A History of African-Americans (1947) and for his leadership on President Clinton’s 1997 National Advisory Board on Race.

Franklin donated a small collection of his personal papers to Duke in 2003. This large addition, donated by Franklin’s son and daughter-in-law John Whittington Franklin and Karen Roberts Franklin, completes the archive of one of the twentieth century’s most distinguished public scholars.

After receiving a doctorate from Harvard in 1941, John Hope Franklin taught at St. Augustine’s University, North Carolina Central University, Howard University, Brooklyn College, University of Chicago, and Duke University—breaking many racial barriers along the way. Deeply involved in the Civil Rights movement, he worked with Thurgood Marshall on the Brown v. Board of Education case and joined protestors in the march led by Martin Luther King, Jr., from Selma to Montgomery, Alabama. He was the recipient of more than 100 honorary degrees, and President Clinton awarded him the Medal of Freedom in 1995. He died in Durham, North Carolina, in 2009.

The donation of papers includes diaries, correspondence, manuscripts of writings and speeches, awards and honors, extensive research files, photographs, and video recordings. The collection also includes materials that trace the Franklin family’s personal history, including their long involvement with the civil rights struggle in Tulsa, Oklahoma.

The papers will be held in the John Hope Franklin Research Center for African and African American History and Culture, part of the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Duke. The papers will open for research after conservation review and archival processing are complete. The opening will be announced on the Rubenstein Library’s website.

“John Hope Franklin always wanted his papers to have an academic home where they would get into the hands of students and scholars quickly,” noted John W. Franklin. “He wanted to make sure that they would be used. We found such a home for his papers in the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library of the Duke Libraries with a dedicated staff to care for the collection.”

The Duke University Libraries will celebrate the John Hope Franklin papers with a reception on September 14, 2012, at 5:30 p.m. in the Gothic Reading Room of the Rubenstein Library. The event is free and open to the public.