Post contributed by Mattison Bond, Project Research and Outreach Associate, John Hope Franklin Research Center

Highlighting Oral Histories by State Part 1

After the Civil War, newly freed African Americans began to utilize their newfound rights and freedoms to improve their lives across the South. The Reconstruction era (1865-1876) stands as one of the most progressive periods for African Americans. During this time, Black Americans were actively participating in government, establishing schools, and creating opportunities for housing and employment. But this period of progressiveness did not last forever. The return of the Democratic party and white supremacists to political power, along with the withdrawal of Northern intervention, plunged the South into the period known as Jim Crow (approx. 1880s-1950s).

Jim Crow laws, created and enforced by southern state legislatures institutionalized racial segregation and the disenfranchisement of African Americans. These laws would impact almost every aspect of Black life and essentially roll back most of the progress that was made by African Americans during Reconstruction. What came next would leave a lasting impression on the world. African Americans of all ages, occupations, and backgrounds would begin standing up for their rights. Courageous leaders, determined students, resilient activists, and everyday people would begin boycotting and challenging Jim Crow throughout the country. The Civil Rights Movement (approx. 1950s-1970s) would change the country as they knew it and ultimately lead to the destruction of the Jim Crow system.

The Behind the Veil digital collection offers a rich and irreplaceable repository of oral histories, images, and administrative files from the people that experienced Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement across the South. The collection features the personal histories of individuals from a wide array of occupations and backgrounds. Researchers can navigate the collection using filters to locate historical accounts by occupation, format, and location. To assist you in exploring, the John Hope Franklin Research Center has chosen a few unique examples from different locations within the collection.

We hope you enjoy!

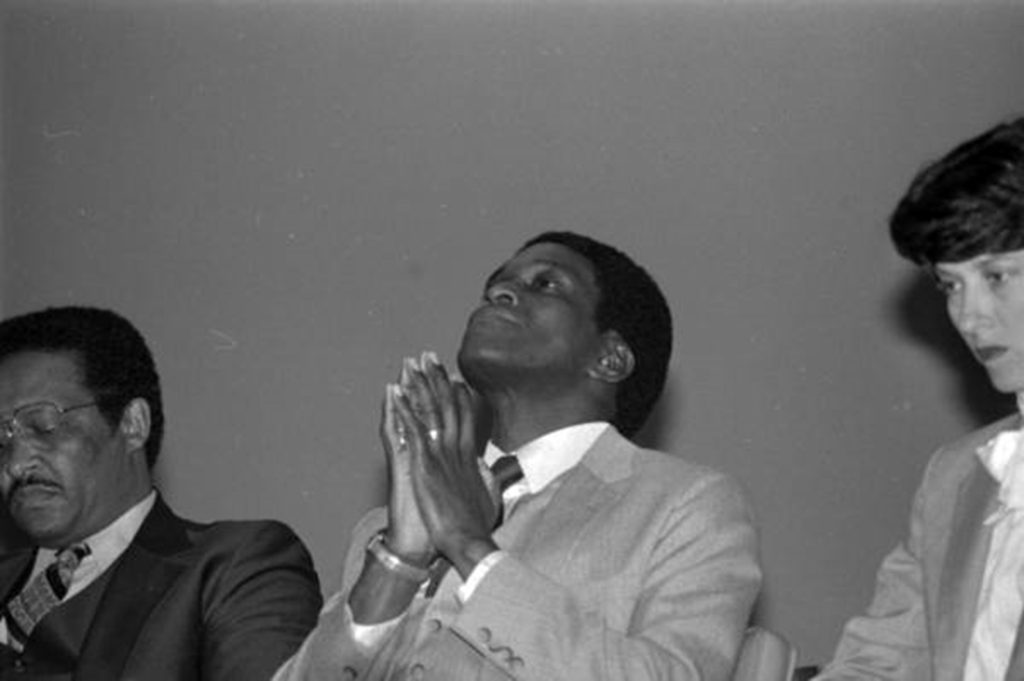

Alabama is one of the larger location tags within the collection with over 200 photographs and 100 oral histories. Start your search by listening to the oral history of one of the more famous interviewees within the collection: Johnny Ford, the first African American mayor of Tuskegee Alabama.

Johnny Ford was born “deep in beautiful Bullock County” Alabama. He was adopted by his uncle at the age of four, moving to Tuskegee. He shares his experiences growing up in Tuskegee, detailing not only racial segregation but also divides in social and economic classes. With his everyday observations of segregation, he also reflects on when the idea of becoming mayor first crossed his mind.

[10:53] “We would have to watch the games from a tree, climb up in the tree and look over and watch the little White boys and girls playing in the park, playing ball. I used to hear my parents complain about that, and they said, “We are paying for these parks just like everybody else, yet we can’t get in.” I had read about Al Clayton Power and heard about him being elected and all of this. I said, then I remember saying to the guys, we would have to peep through the fence, and I said, “The mayor of this town must be a powerful dude, if he can keep us out of this park. One day I think I’d like to be mayor of this town.”

Ford would go on to be involved in the Civil Rights movement in Knoxville, TN as he attended college. He would work on the Kennedy campaign in 1968 and later help to elect the first two African Americans to the Alabama legislature. Johnny Ford served as the Mayor of Tuskegee from 1972- 1996, and then again in 2004 and 2012.

You can hear the voice of Mayor Johnny Ford by listening to his oral history here:

Johnny Ford interview recording, 1994 July 13 / Behind the Veil / Duke Digital Repository

There are a total of 64 oral histories that are available under the Arkansas location filter. Within these 64 items you can find the oral history of Willie Lucas. While there are a total of three midwives mentioned throughout the collection, Willie Lucas is the only midwife that has a recorded oral history.

Willie Lucas was born in Hughes, AR in 1921. The daughter and granddaughter of midwives, Lucas was convinced she would not follow in her mother’s footsteps. She recalls her mother waking up in the middle of the night to deliver babies, sometimes having to travel through the cold and rain.

[8:52] “They didn’t have any cars and she would come in sometime and raining in the wintertime and her clothes would be frozen stiff on her. She’s be standing up and I said “Lord I’ll never be a midwife.””

That sentiment did not last long. Lucas would later train to be a midwife, shadowing her mother. The first time she delivered a baby, the parents named the child after her. Within her interview she speaks about the differences of midwifery during her time in the 40s and that of her mother’s time. She details the types of tools that were used, the ways that they were paid, the home remedies that helped with the birthing process, and the obstacles that the medical field posed to midwives.

Her oral history contains two parts and a transcript. You can listen to Willie Lucas’s oral history here:

Willie Lucas interview recording, 1995 July 07 / Behind the Veil / Duke Digital Repository

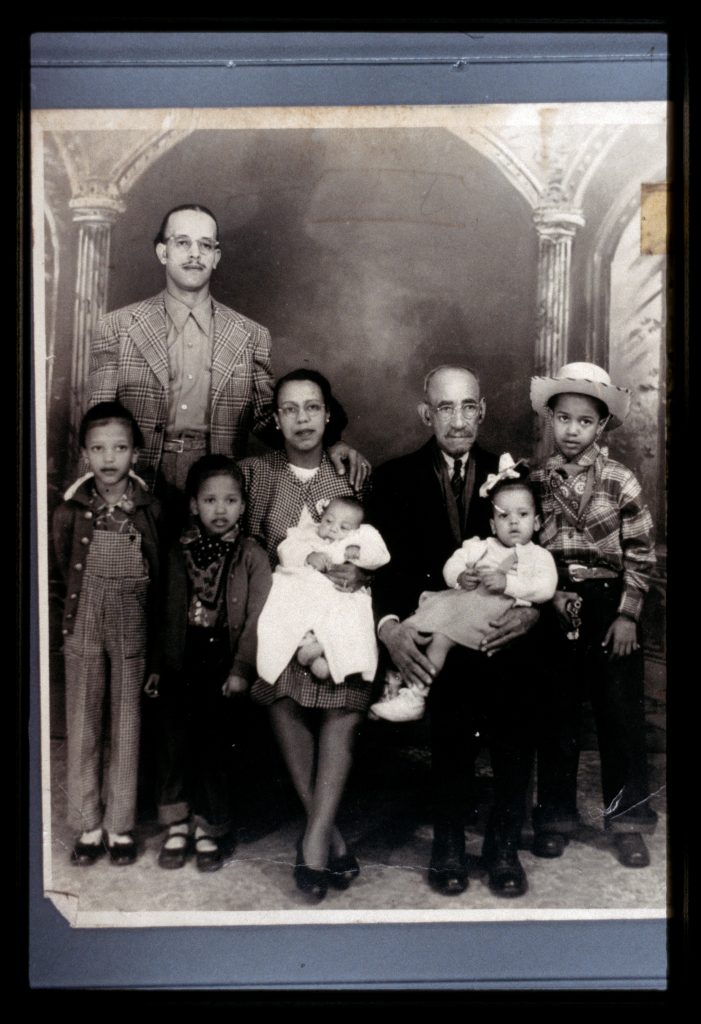

There are a total of 216 items that can be found under the Florida location filter. Within these items you can find the oral histories, administrative files, and specifically a collection of images of students and faculty at Florida A&M University, thanks to Sue Russell.

Born in Milton, Florida in August 1909, Russell was the daughter of a teacher and brick mason. She recalls that her mother encouraged education for her and her siblings. They attended school up until the 6th grade in Milton, until they were sent to Pensacola to finish high school.

[44:00] “The biggest problem we had was school problem, I guess, because after we finished the sixth grade there as—Well, they used to call us Negros then. We couldn’t go to school with the Whites… We had to leave Milton for Escambia, or go somewhere else if we wanted to finish high school.”

Sue Russell first attended Florida A&M College in 1928, graduating two years later with courses in business administration. In 1943, she re-enrolled and eventually completed her four-year degree. It was in school that Russell admits to experiencing her first taste of racial discrimination. Further into the interview she talks about campus life, her ambitions to be a home economics teacher, and some of the discrimination she experienced. Even more interesting is the numerous pictures of students and faculty that attended Florida A&M during the time that Russell was enrolled.

You can listen to Sue Russell’s interview here:

Sue Russell interview recording, 1994 August 05 / Behind the Veil / Duke Digital Repository