Post contributed by Sarah Bernstein, Josiah Charles Trent History of Medicine Intern.

The History of Medicine artifacts collection presents such a unique opportunity to work with material sources in the history of medicine. In the same way that there is a difference between viewing manuscripts through photographs and seeing them in person, there is something striking about being able to hold an object that you have only read about in books and pamphlets. In my training as a historian, I have been largely trained and relied on primary sources in the form of written materials. It is precisely because of this that I have been thrilled to be able to view and work with the History of Medicine artifacts collection.

Amongst the many marvelous and unexpected items in the collection, from amputation sets and bone saws to carved ivory manikins and elaborate anatomical flap books, I found myself drawn to the multiple British nineteenth century medicine chests within the collection. These stately century solid wood boxes contained custom glass bottles, fitted to each box’s measurements, with some still filled with powders and liquids. Going through them was nothing short of opening a time capsule and a treasure chest at the same time.

Medicine chests like these can provide a window into the past to understand not only nineteenth century medicine, but global, local, and cultural developments as reflected in the items in these chests and the existence of these chests themselves. There are some medicine chests that are smaller than others, with a variety of cork-stoppered bottles, and were likely meant to be portable and used while traveling. Other medicine chests are heavier and equipped with preparatory tools and medical instruments. These large medicine chests were meant to be stationary, within homes or on ships. In England, both types of medicine chests emerged in the context of newfound social and physical mobility for the Victorian public.

Regardless of whether they were meant for travel or to be stationary, the existence of these chests speak to the common practice of self-healing, an anticipated absence of a physician, an expected level of medical literacy, and an interest in maintaining one’s own health. These chests are more similar to our contemporary medicine cabinets and in the household, functioned less like a first aid kit or a form of triage support. Rather than immediately, and always, calling upon a doctor, people would often utilize herbal and botanical knowledge to create remedies at home to alleviate and treat their ailments before turning to a physician. And what exactly did people use as medicine?

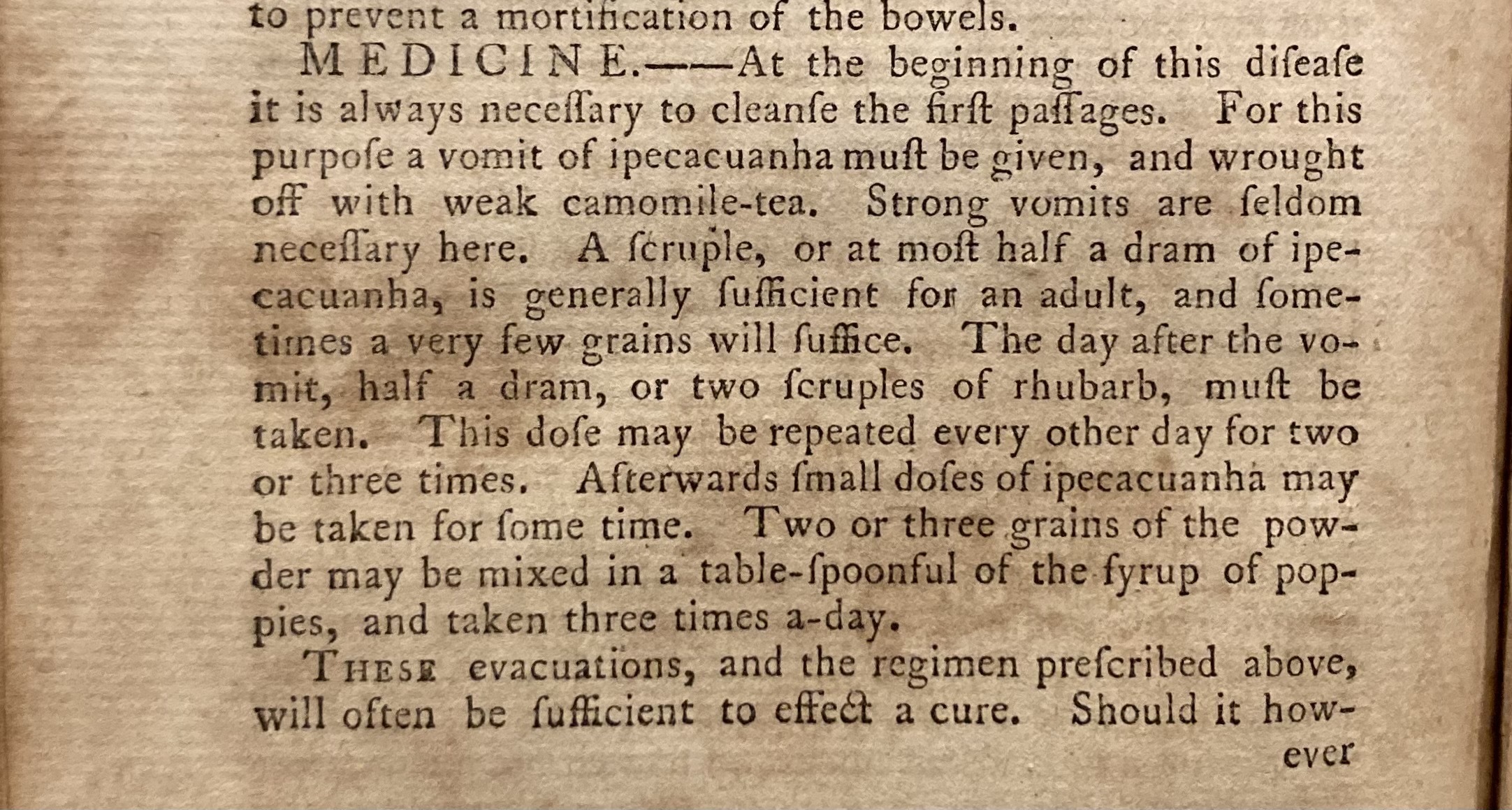

In one “home medicine chest” there are bottles of Ipecacuanha (Carapichea ipecacuanha) in various forms. Ipecacuanha is a slow growing plant native to Central and South America that has a long history in British medicine as to treat dysentery, poisoning, fever, and colds. It was commonly prepared as syrup of ipecac, or simply “ipecac,” which would be used to empty the stomach to combat poisoning. Ipecacuanha was also used in Dover’s Powder, a bottle of which also appears in the same home medicine chest, which was a mixture of powdered ipecacuanha, potassium sulfate, and powdered opium as a pain reliever and to treat fevers and colds by inducing sweating.

The same home medicine chest also contains multiple instances of rhubarb: tincture of rhubarb, one simply labeled as “Rhubarb,” and the other specified as “Powder of Turkey Rhubarb.” While today rhubarb may conjure thoughts of confectionery sweets and strawberry and rhubarb pie, rhubarb has historically been prized for its medicinal properties and was highly sought after. Rhubarb itself refers to a species of plant, Rheum palmatum, that native to parts of western China and northern Tibet. It was used to aid in cases of indigestion and as a laxative.

Similarly to ipecacuanha, rhubarb and its various preparations can reveal the rich history and practice of herbal and botanical medicine that persisted into the nineteenth century. Despite both of the plants being non-native to Britain, where these chests were created and their clientele were located, ipecacuanha and rhubarb were popular and common treatments utilized throughout the nineteenth century. The prevalence of ipecacuanha and rhubarb not only serves as an indication of the widespread use of purgative medicine during that era but also hints at the emergence and growth of industries, trade networks, and international relationships necessary for the accessibility of these medicinal plants.

Exploring the world through a home medicine chest is a unique and insightful perspective. It’s fascinating how the contents of such a seemingly ordinary space can provide a window into various aspects of life—health, culture, traditions, and even personal stories. This approach offers a holistic understanding of not just the physical well-being of individuals but also the social and cultural contexts that shape their lives. By delving into the items within a medicine chest, one can uncover a wealth of knowledge about the diverse ways people navigate health and wellness. This thoughtful exploration highlights the interconnectedness of our global community and the rich tapestry of human experiences.

VOIR Magazin