Post contributed by Janice Hansen.

No one can describe the focal points of the Jantz Collection better than Harold Jantz himself. He described the better part of his book-collecting career as “amateur,” marked by “casual collecting according to personal tastes and interests.” Jantz did not consider himself a “bibliophile,” but rather a “reader and an explorer” (Jantz, xxii). This description rings particularly true when considering the Harold Jantz Collection as a whole. Duke University acquired the Jantz Collection in 1976. With approximately 10,500 volumes, it provides one of the most comprehensive and unique explorations of German Baroque literature in the United States. The collection highlights the areas in which Harold Jantz was most interested, including German Americana, Faustian and Goethean material, the occult, and more. In addition to these volumes, the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library holds the personal papers of Harold Jantz; a collection of 170 early manuscripts, music manuscripts, and autograph albums; and a graphic art collection consisting of engravings, etchings, and other prints with dates ranging from the 1400s to the 1800s.

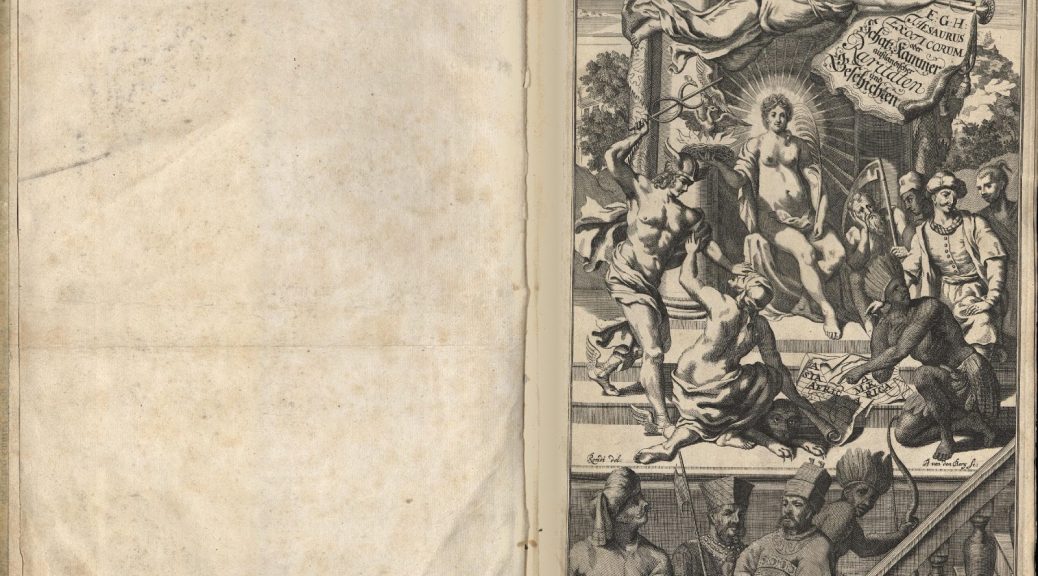

The manuscript fragment through which I got to know the Jantz collection was used to bind Eberhard Werner Happel’s 1688 Thesaurus Exoticorum, a fascinating piece in and of itself. There are a number of reasons why this particular volume would have been of great interest to Harold Jantz, the great explorer of German Baroque literature. Happel’s work is a compendium of information in the German tongue. It collected news and curiosities, ordering these snippets of information and illustrating them profusely with intricate woodcuts.

Works like these have only begun to garner scholarly attention in recent years, but Jantz saw the value in the lesser-known authors and works. The Thesaurus Exoticorum is peppered with information about the Americas, placing it in the genre of Americana, another of Jantz’s collecting focal points. Happel considered reading to be a replacement for experience, this text thus allowing readers more knowledge in reading it than with many years of world travel. The icing on the cake for such a Baroque and Americana-filled work is then its fine binding.

But what Jantz likely didn’t know, was just how unique of a binding it truly was. Using leaves of unwanted, outdated, or worn manuscripts to bind other works was a common bookbinding practice in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. This practice gave new life to materials that would otherwise be discarded. The manuscript waste on Happel’s work has its own story to tell, and a fascinating one at that.

While we did not know much about the unidentified fragment when we first started, we now know significantly more. Poking around on Google led me to a 1438 Middle Dutch text with striking linguistic similarities to the fragment. The Middle Dutch text was a translation of the Legenda aurea, or Golden Legend, by Dominican friar Jacobus de Voragine. The Golden Legend is a collection of hagiographies, originally compiled in the latter part of the thirteenth century. The text was incredibly popular in both the original Latin and in vernacular translation from the thirteenth century and well into the early modern period. There are approximately 200 different manuscript versions in German, and scholars have spent much time looking at these versions and trying to construct a history of German textual transmission.

Both leaves were part of the same hagiography, detailing the life of the Apostle Peter. What makes them especially interesting is that these two leaves relate the actions of Nero and his many horrific deeds. The description of Nero’s misdeeds is very detailed, a striking difference from many of the popular and widely-disseminated manuscript traditions of the Golden Legend in Germany. Comparing this fragment to the most popular German translations of the Golden Legend left us with more questions than answers. Our fragment aligned much more closely with the original Latin tradition.

The fragment begins with the crucifixion scene of the Apostle Peter and then moves into further description of Nero’s deeds. Particularly gruesome are Nero’s slicing open of his mother’s womb to see how he once grew inside of her and his insistence that he experience pregnancy for himself. To fulfill this desire of knowing how great his mother’s labor pains were, Nero’s doctors give him a drink that secretly has a frog in it. The frog grows inside of Nero and is finally expelled through “childbirth” with the help of another secret drink. The frog emerges covered in slime and blood. Nero’s homosexuality is also mentioned explicitly, differentiating this version of the Golden Legend from more popular translations.

With further research we discovered similarities between our fragment and the Harburger Golden Legend, which exists only in one almost-complete manuscript and of which there were only five other known fragments. Based on the paleography (handwriting) and linguistic forms, our fragment is even older than the only full manuscript version of the Harburger Golden Legend, which was created between 1450 and 1475. The fragment used to bind Happel’s book dates to the first half of the 15th century, making it now the oldest known exemplar of the Harbuger Golden Legend.

From this single piece, we can see many of Harold Jantz’s collecting interests at play—Baroque German literature, Americana, and unique and interesting bindings. The Harold Jantz Collection is filled with research possibilities, and it is a collection I have turned to time and time again for many different research projects. Over 2,000 items from the Jantz Collection are digitized and included in the Internet Archive, making a number of unique materials open and accessible for research. The David M. Rubenstein Rare Book & Manuscript Library also offers the Eleanore and Harold Jantz Fellowship to support researchers drawing heavily from the collection.

Works Cited:

Research on the Jantz Collection and the manuscript fragment was a joint effort between myself and UNC faculty member Ruth von Bernuth as part of my studies in the Carolina-Duke Graduate Program in German Studies. We are especially thankful to former Duke faculty member Ann Marie Rasmussen for leading us to the fragment and to Andrew Armacost for his support on the project. For further reading on the manuscript and the Jantz Collection in German, you can check out our work published in the Zeitschrift für deutsches Altertum und deutsche Literatur (ZfdA).

Thank you for your interesting article on the Jantz Collection.

The acquisition of the Harold Jantz Collection was primarily through the efforts of Professor Frank Borschardt of the German Department. When it was acquired, I was Curator of Rare Books. My student assistant, Greg Cox, and I went to his home in Baltimore and spent five days packing the collection–each one separately wrapped and boxed–to be brought to Duke in a specially designated semi-trailer moving truck with special instructions from Prof. Jantz that the boxes be stacked no more than 2 high and tied down to prevent shifting. And, furthermore, there were to be no other stops on the way from his house to the Duke Library.