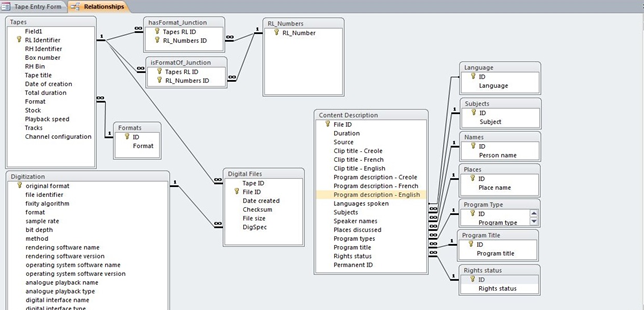

The Radio Haiti archive project is underway! We’ve spent the first couple weeks creating a behemoth database…

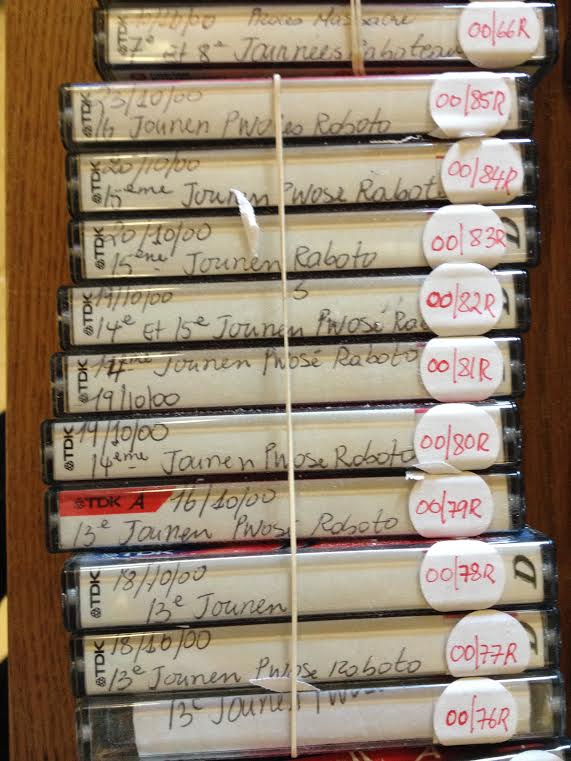

…assigning each and every tape a unique ID number, and putting the tapes in nice new comfortable bar-coded boxes. This means that an archive which arrived looking like this…

… now, happily, looks like this.

We are incredibly fortunate that the former Radio Haiti staff and friends and family in Port-au-Prince (you know who you are!) sent the tapes with a detailed inventory — it makes our job so much easier.

We are also inspecting the tapes for mold (and we have found mold aplenty).

We are also keeping track of which tapes are going to require a little extra TLC.

We’re creating rather sweeping controlled vocabulary — describing subjects, names, and places that appear in the archive. Once we’ve put in all this metadata, we can send the more than 3500 tapes off to be cleaned and digitized.

These tasks (organizing, typing in data, cross-referencing, labeling, bar-coding, describing, mold-noting), while arguably unglamorous, are necessary groundwork for eventually making the recordings publicly accessible, ensuring that these tapes can speak again, and that Radyo Ayiti pap peri (Radio Haiti will never perish).

We’ve only listened to a small sampling of the recordings so far, but the tapes themselves, as physical objects, tell a story. Even the mold is part of the story. That white mold on the tapes and the dusty dark mildew on the tape boxes tell of the Radio Haiti journalists’ multiple exiles during which the tapes remained in the tropics and the future of the station was uncertain.

To glance over the titles of the recordings — the labels on their spines, lined up in order, row upon row — is to chart the outline of late 20th century Haitian political history — a chronology of presidencies, coups, interventions, massacres, disappearances, and impunity. The eighty-nine tapes chronicling the Raboteau trial of 2000, in which former junta leaders were tried for the 1994 torture and massacre of civilians, take up an entire shelf.

And then there is the long, long sequence of recordings after the April 3, 2000 assassination of Jean Dominique, when the center of the station’s orbit violently and irrevocably shifted.

It is uncanny to look at the tapes with hindsight and see the patterns emerge. Here is the political landscape of Haiti, from the 1970s to the 2000s, from dictatorship to the democratic era: The same impunity, the same lies, the same corruption, the same suffering, the same mentalities, the same machinations. Chameleons change their color, oppressors repaint their faces, state-sanctioned killings become extrajudicial killings, and the poor generally come off the worst.

The journalists who did these reports and conducted these interviews experienced these events in real time. They could not yet know the whole story because, in each of these moments, they were in the middle of it. For them, the enthusiasm of 1986 (after Duvalier fell, and Radio Haiti’s staff returned from their first exile) and of 1994 (when Aristide was reinstated, and Radio Haiti’s staff returned from their second exile) was unfettered. Likewise, for them, the struggle against impunity and injustice was urgent.

There is a recording labeled “Justice Dossier Jando Blocage 4.9.01” — “Justice Jean Dominique case blocked investigation.” Those short words contain a saga: by September 2001, a year and a half after Jean Dominique and Jean-Claude Louissaint were murdered, Radio Haiti was already reporting on how the investigation had stalled. In 2001, perhaps, justice appeared attainable, just out of reach. Now, fourteen years later, the case remains unsolved.

Back in 2011, I attended a talk by Haitian human rights activist Jean-Claude Bajeux in Port-au-Prince, where he said, “gen anpil fantòm kap sikile nan peyi a ki pa gen stati.” (“there are many ghosts wandering through this country that have no statue”). He was speaking of those who were disappeared under the Duvalier regime. But he could have been speaking, too, of innumerable others who have died and been erased – those who were killed by the earthquake, under the military regime, through direct political violence and through the structural violence of everyday oppression.

This archive is not a statue or a monument, but it is one place where the dead speak. Sometimes the controlled vocabulary feels like an inventory of ghosts.

Sometimes I think I am working on an archive that was never meant to be archived, something that was supposed to remain an active, living struggle. I think of how far these clean cardboard storage boxes and quiet temperature-controlled spaces are from the sting of tear gas, the stickiness of blood, the smell of burning tires, the crack of gunfire, the heat and noise, the laughter and fury of Haiti.

But salvaging and preserving are part of the struggle; remembering is, itself, a political act.

Post contributed by Laura Wagner, Radio Haiti Project Archivist.

The Voices of Change project was made possible through a generous grant from the National Endowment of the Humanities.

One thought on “Onè! Respè! (Honor! Respect!)”

Comments are closed.