Post contributed by Madeline Huh, Trent History of Medicine Intern, MSLS student at UNC Chapel Hill.

I’ve been working as the History of Medicine intern at the Rubenstein Library for a little over a month now, and in my short time working here, I’ve had the opportunity to look at some truly remarkable materials–from the gorgeous illustrations of Elizabeth Blackwell’s A curious herbal, to handwritten notebooks by nineteenth-century Japanese physicians, to an atlas of midwifery from 1926. And, of course, I’ve also had the chance to look at fascinating historical artifacts like the 16th century Scultetus bow saw, an 18th century trephination kit, and a very intriguing little box of pills labeled as “female pills.”

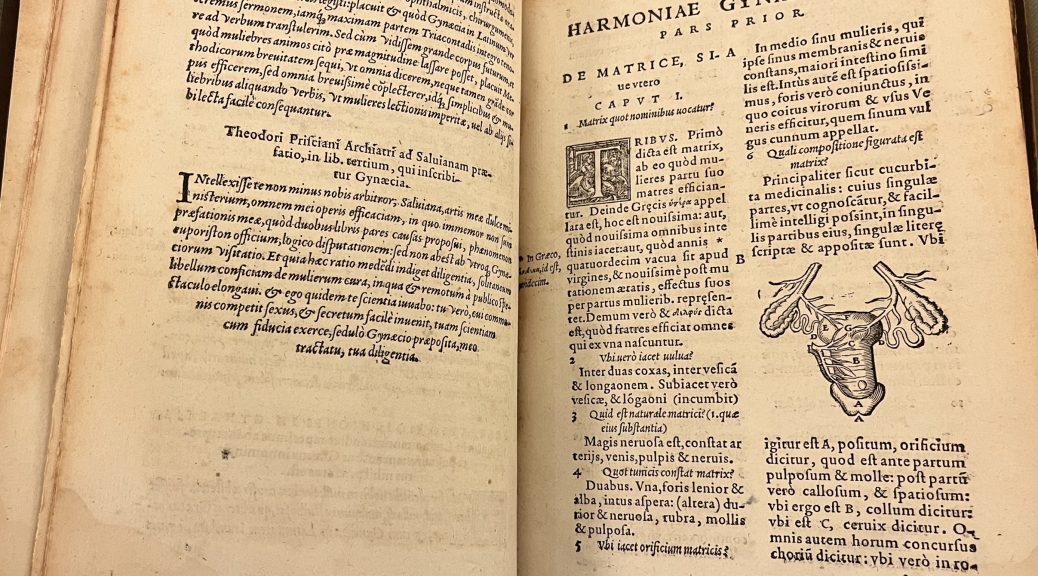

One of my favorite books I’ve encountered so far has been the Gynaeciorum, an encyclopedia of obstetrics and gynecology compiled in the 16th century by Conrad Gessner and Hans Kaspar Wolf. It is the first gynecological encyclopedia to be published, and I was surprised to discover that an entire book was dedicated to this topic in the 16th century. The Gynaeciorum combines the works of several different ancient and medieval medical authors who wrote about women’s health. A few of these include Trota, a twelfth-century female physician and medical writer; Abū al-Qāsim Khalaf ibn ʻAbbās al-Zahrāwī, one of the great surgeons of the Middle Ages; and Muscio, the author of a treatise on gynecology from ca. 500 CE.

The subject matter of the book often goes beyond what we generally think of as the realm of gynecology and obstetrics, exploring neonatal and pediatric inquiries as well. One section asks, “What should be the first food that we give to an infant?” The provided answer is, “Something like bread–that is, crumbs poured into honey-wine, preserved fruit, or milk, or perhaps a drink made of spelt, or porridge” (Gynaeciorum, 79–translation from Latin is my own). Other inquiries discuss menstruation, pregnancy, childbirth, and postpartum health.

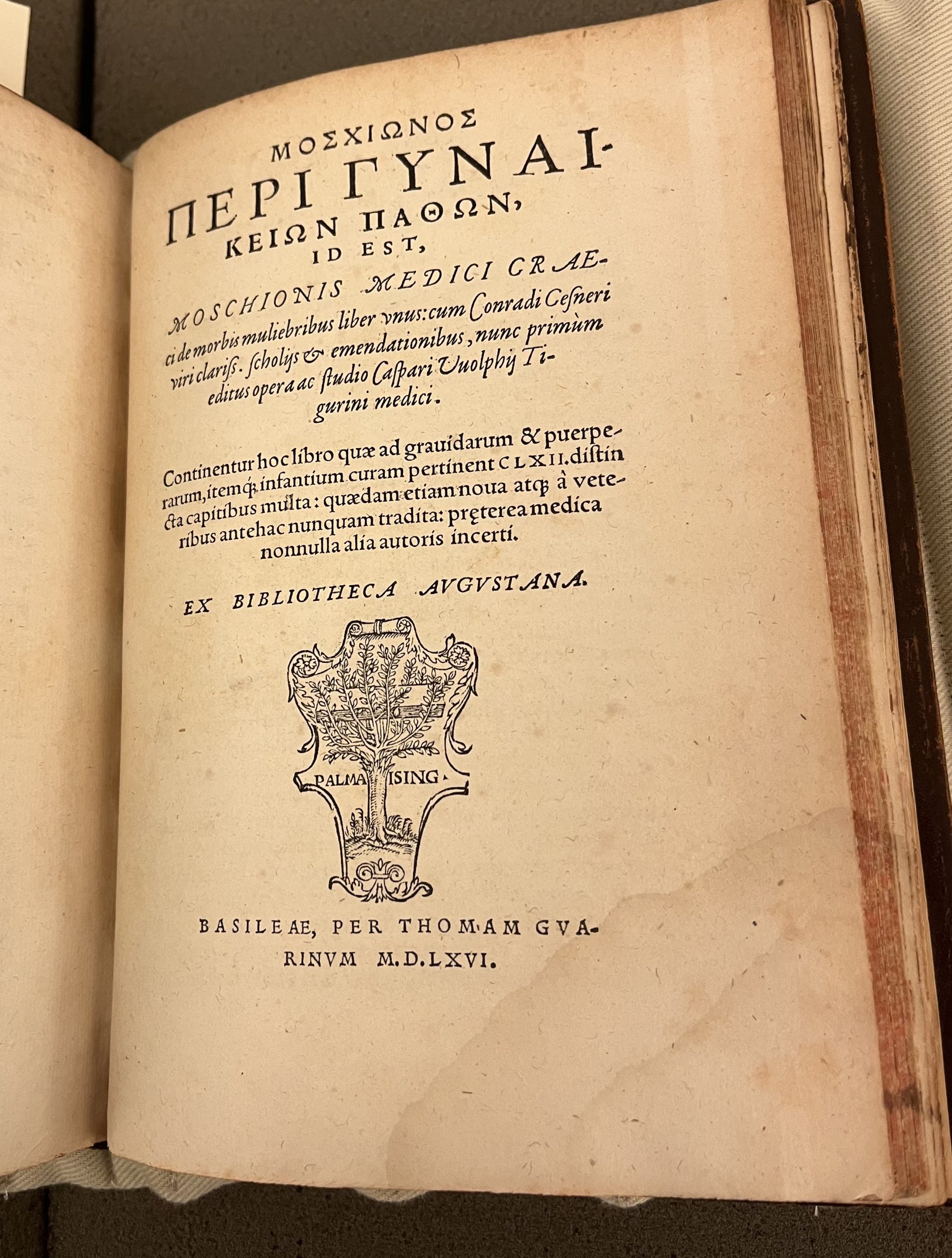

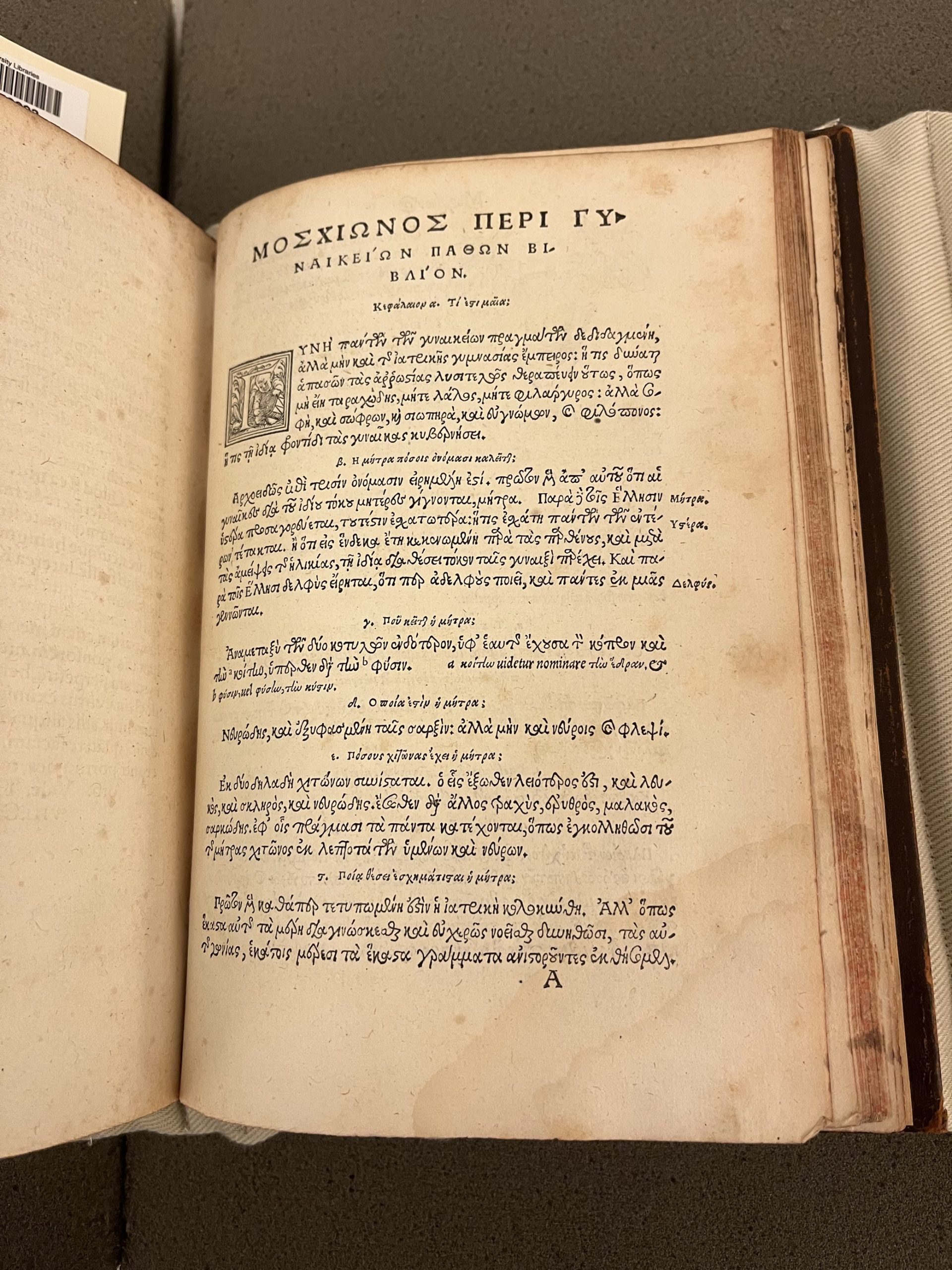

I was also very intrigued to find the first printed edition of Muscio’s Gynaecia at the back of the book, printed in Greek no less, which struck me as unusual. In medieval Europe, it was more common for Greek works to be translated and disseminated in Latin, rather than the other way around. Literacy and interest in Greek in the west decreased during this period before a revival of interest in Hellenistic culture and language occurred during the Renaissance. I did a little research on the medieval manuscript transmission of Muscio, and what I discovered was a very convoluted story of translation, retranslation, and misattribution.

According to Monica Green, a historian of medieval medicine and women’s health, Muscio (who is also known as Mustio in some places–not to be confused with Moscion, who is another ancient medical writer entirely) originally wrote a treatise on gynecology in Latin around 500 CE known as the Gynaecia. This was probably a translation and paraphrase of the Greek Gynaikeia by the physician Soranus of Ephesus who was active around 100 CE. Muscio’s work was copied into several manuscripts in western Europe during the 9th, 10th, and 11th centuries, and his work was popularized later in the Middle Ages, eventually being translated into French, English, Dutch, and Spanish. But intriguingly, Muscio’s treatise on gynecology was also translated into Greek within the Byzantine Empire. Finally, in 1793, the Greek translation was retranslated back into Latin by Franz Oliver Dewez! I can only wonder how close (or far) Dewez was to Muscio’s original language and phrasing.

All of this was fascinating to learn. Looking at the edition of Muscio in the back of the Gynaeciorum, we see that Gessner and Wolf, who were working in the 16th century, have chosen to present it in its Greek form. I wonder, then, did Gessner and Wolf know about the manuscript transmission of this text and that it was originally written in Latin? I assume they did, based on the fact that we see a Latin preface to Muscio’s Gynaecia included at the very beginning of the Gynaeciorum. So did Gessner and Wolf include the Greek version in the book to appeal to contemporary interest in Greek language and literature, or for another reason? And what information about women’s health and childbirth has been lost or misinterpreted in the process of translation and retranslation? My deep dive into Gessner, Muscio, Soranus, and the transmission of gynecological texts has left me with even more questions than I started with.

Further Reading:

- Monica Green (2023), “‘Cliff Notes’ on the Circulation of the Gynecological Texts of Soranus and Muscio in the Middle Ages,” https://hcommons.org/deposits/objects/hc:59420/datastreams/CONTENT/content

Congratulations on the article, it is very accurate. We often underestimate the knowledge and skills of people who lived in past eras, but when you study history in depth you realize that certain disciplines were already highly developed centuries ago.