Post contributed by Zachary Tumlin (Project Archivist for the Economists’ Papers Archive), Andrew Armacost (Head of Collection Development), Laura Micham (Director of the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture), and Vincent Carret (2021-2022 HOPE Center Visiting Scholar and 2022 Summer in the Archives Fellow).

On Monday, June 27th, around two dozen participants in the Center for the History of Political Economy’s (HOPE Center) 2022 Summer Institute met with four staff members from the David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library for a showing of items from the Economists’ Papers Archive (a joint venture between the HOPE Center and Rubenstein Library). The Summer Institute was started in 2010 with funding from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) and is a two-week long annual event that brings together faculty and PhD students in economics to examine various topics in the history of the field. This year’s focus was on preparing participants to design and teach their own undergraduate-level course on the history of economic thought, along with showing how such concepts and ideas might be introduced into other classes. The instructors were Duke faculty members Bruce Caldwell (HOPE Center Director), Steven Medema, and Jason Brent.

What follows are contributions from Andrew Armacost (Head of Collection Development), Laura Micham (Director of the Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture), Zachary Tumlin (Project Archivist for the Economists’ Papers Archive), and Vincent Carret (2021-2022 HOPE Center Visiting Scholar and 2022 Summer in the Archives Fellow) about what they displayed during this event.

Andrew Armacost

While many of the collections in the Economists’ Papers Archive relate to documenting the careers of individual economists, the archive also holds some related collections that offer a larger context for the history and range of work that encompasses this discipline.

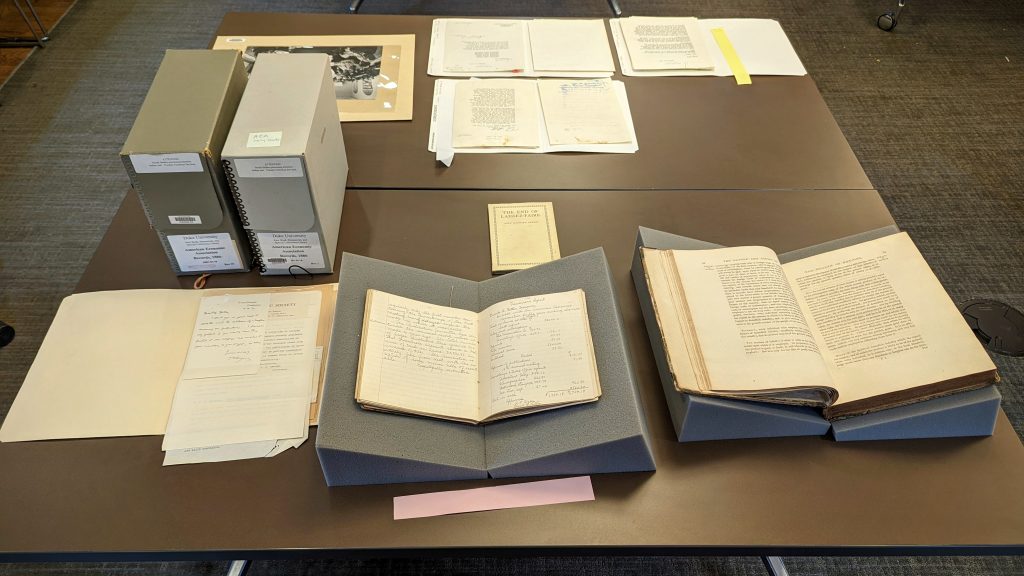

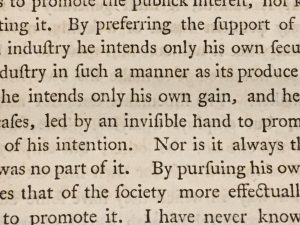

Starting at the bottom right and going clockwise, one goal of the Archive is to chronicle the historical development of the field, and a key early work in this narrative is Adam Smith’s An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations, published in 1776. This work explores the role of markets, international trade, and economic decision making. In it, Smith famously describes market forces acting as an “invisible hand” that guides economic decision making.

The Archive also holds organizational papers, including those of the American Economic Association (AEA; founded in 1885) and its journal American Economic Review. These papers represent more than a century of economic thought and the participation of a broad range of economists, and include correspondence from international economists like John Maynard Keynes, who corresponded on behalf of the Royal Economic Society.

The Archive also holds the papers of economists working in government, such as Federal Reserve Chairman Arthur Burns, who served during the Nixon administration. This collection preserves correspondence between the President and Chairman and their discussions related to economic policy and decisions related to the administration’s ending of the gold standard for US currency.

Laura Micham

The Economists’ Papers Archive holds the papers of several prominent women economists, such as Anita Arrow Summers, Anna Schwartz, Juanita Morris Kreps, Charlotte Phelps, and Barbara Bergmann. Though these scholars emerged from a range of backgrounds and intellectual traditions, and each took different professional paths, they all seem to have been animated by an interest in living independent lives and a realization that financial independence was crucial to that goal.

During this event, I shared materials from each of these collections that offer a window into these women’s contributions to the field of economics and to society:

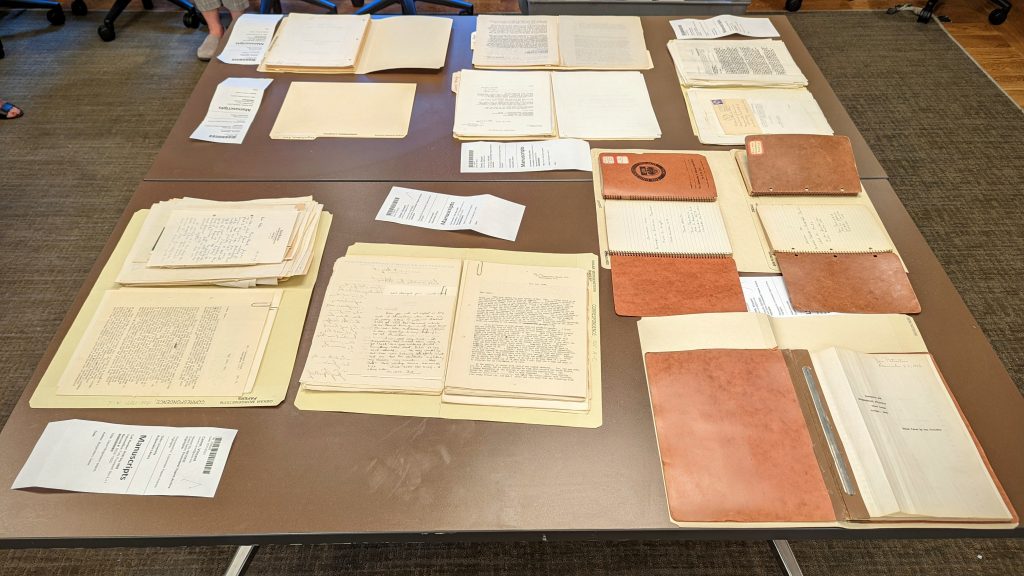

- Bottom left: Professor Arrow Summers’s graduate student work during the mid-1940s in the University of Chicago Economics Department.

- Bottom right: Detailed correspondence between Professor Schwartz and Milton Friedman related to their groundbreaking work, A Monetary History of the United States, 1867-1960 (Princeton University Press, 1963).

- Top right: Memos and other correspondence between Professor Kreps and President Jimmy Carter when she served as Secretary of Commerce in his administration.

- Top left: Heavily annotated writings of Professor Phelps documenting her contributions to behavioral economics.

- Top middle: Handwritten manuscripts detailing Professor Bergmann’s groundbreaking scholarship on women and children.

Barbara Rose Bergmann (20 July 1927—5 April 2015) was a feminist economist. Her work covers many topics from childcare and gender issues to poverty and Social Security. She was a co-founder and President of the International Association for Feminist Economics, a trustee of the Economists for Peace and Security, and Professor Emerita of Economics at the University of Maryland and American University. During the Kennedy administration, she was a senior staff member at the Council of Economic Advisers and a Senior Economic Adviser at the Agency for International Development (USAID). She also served as an advisor to the Congressional Budget Office and the Bureau of the Census.

Bergmann’s archival collection consists of published writings, including congressional testimony, as well as research and project files, and a selection of career awards and books from her library. One of the manuscripts included in the display is “A ‘cost-sharing’ formula for child support payments.” This undated piece was written in pencil on sheets from a legal pad, copiously revised, meticulously calculated, and thoroughly argued. She published several scholarly and journalistic articles on the topic of child support, some likely emerging from this piece, including an article co-authored with Professor Sherry Wetchler in Family Law Quarterly, Fall 1995, Vol. 29, No. 3, “Child Support Awards: State Guidelines vs. Public Opinion” [Duke NetID required for access].

Zachary Tumlin

Starting at bottom right and going counterclockwise: Carl Menger papers, Kenneth J. Arrow papers, Vernon L. Smith papers, and Marc L. Nerlove papers.

Since I began in February, I have been processing a new acquisition: the Marc L. Nerlove papers. The papers primarily document the professional career of economist Marc Nerlove, who specializes in agricultural economics and econometrics (the use of economic theory, mathematics, and statistics to quantify economic phenomena). Upon his election to the AEA as a Distinguished Fellow in 2012, he was recognized for creating a widely used template having to do with the dynamics of agricultural supply, pioneering the development of modern time series methods and the analysis of panel data in econometrics, and being the first to apply duality theory to estimate production functions. During his 60-year career, he held appointments at Johns Hopkins, Minnesota, Stanford, Yale, Chicago, Northwestern, Pennsylvania, and Maryland; worked as a consultant at the World Bank, International Food Policy Research Institute, and RAND Corporation; and was awarded the 1969 John Bates Clark Medal from the AEA.

Like what Vincent will detail next about the highly influential economics department at Chicago, I chose material that showcases his own connections there:

- Material related to his father, Samuel H. Nerlove, who came to the U. S. from Russia as a toddler in 1904 with his parents, who settled in Chicago; Samuel was a professor in business economics at Chicago from 1923-1965:

- 1939 syllabus for Business Economics 1.

- 1972 letter and eulogy from former student and then U. S. House Representative Sidney Yates.

- Volume 22, number 2 of issues/ideas (Graduate School of Business magazine) from 1974, sent by Dean James Harper at the request of Nerlove’s mother Evelyn (with letter indicating this); includes article “Hunt’s ‘Why’ Unveiled” about unveiling of artist Richard’s Hunt sculpture “Why”, commissioned by the Samuel H. Nerlove Memorial Fund.

- Material from his time as a student at Chicago and Johns Hopkins:

- 1953 letter from economist John Nash (subject of the book and film A Beautiful Mind), apparently in response to a letter from Nerlove with a question about utility function.

- Draft of introduction to Studies in the Quantity Theory of Money by Milton Friedman (published in 1956) and class notes for Friedman’s 1955 course on the same topic (including doddles of trains, a subject Nerlove would write about early in his career in the context of railroads).

- Material from his time as a professor at Chicago from 1969-1974:

- 8×10 inch black and white headshot.

Letter from his secretary Gloria Feigenbaum upon his departure for Northwestern (pictued right), as well as a candid print of the two of them. Such staff maintained his on-campus files, which are now part of this archival collection, but these people can become invisible without thoughtful description. In this letter, she expresses how he had occasionally forgotten his purpose (research), interfered in matters that were her responsibility (administrative), and prevented her from exercising the degree of initiative that she was used to and capable of, but that she chosen to remain quiet to preserve their good working relationship.

Letter from his secretary Gloria Feigenbaum upon his departure for Northwestern (pictued right), as well as a candid print of the two of them. Such staff maintained his on-campus files, which are now part of this archival collection, but these people can become invisible without thoughtful description. In this letter, she expresses how he had occasionally forgotten his purpose (research), interfered in matters that were her responsibility (administrative), and prevented her from exercising the degree of initiative that she was used to and capable of, but that she chosen to remain quiet to preserve their good working relationship.- Folder of early 1970s material from the Political Economy Club at Chicago (graduate student group). It includes three issues of their Journal of Progressive Hedonists Against Rational Thought (JPHART), a caricature of Nerlove that has him beside the White Rabbit and someone as Alice from one of his favorite books—Alice in Wonderland (these sketches appeared at the end of each issue of JPHART), a script of a skit set in the department that mentions Nerlove, and a copy of Sir Dennis H. Robertson’s poem “The Non-Econometrician’s Lament.”

Vincent Carret

What brings together Leonid Hurwicz, Paul Samuelson, Don Patinkin, and Oskar Lange? Apart from the fact that they were all major economists by any standard (two of them received the Nobel Prize), they were also all affiliated with the University of Chicago at some point.

In the material I presented, this connection is the link between them. Starting at the bottom right and going counterclockwise are a few of Patinkin’s student notebooks, of which there are dozens. At Chicago, Patinkin attended classes taught by the likes of Jacob Viner, Frank Knight, Jacob Marschak, and Oskar Lange—in particular, Lange’s course on Mathematical Economics and Stability Analysis held during the first half of the 1940s.

It was on this very subject of economic stability that Lange corresponded with Samuelson, who earned his undergraduate degree from Chicago. Their letters on the stability of an economic model called general equilibrium were exchanged in 1942, before Lange published his 1944 Cowles Commission monograph on Price Flexibility and Full Employment. These letters, shown here next to Patinkin’s notes, were duly kept by Samuelson and are now available in his collection of papers, rich in hundreds of folders of correspondence with almost every economist of the 20th century.

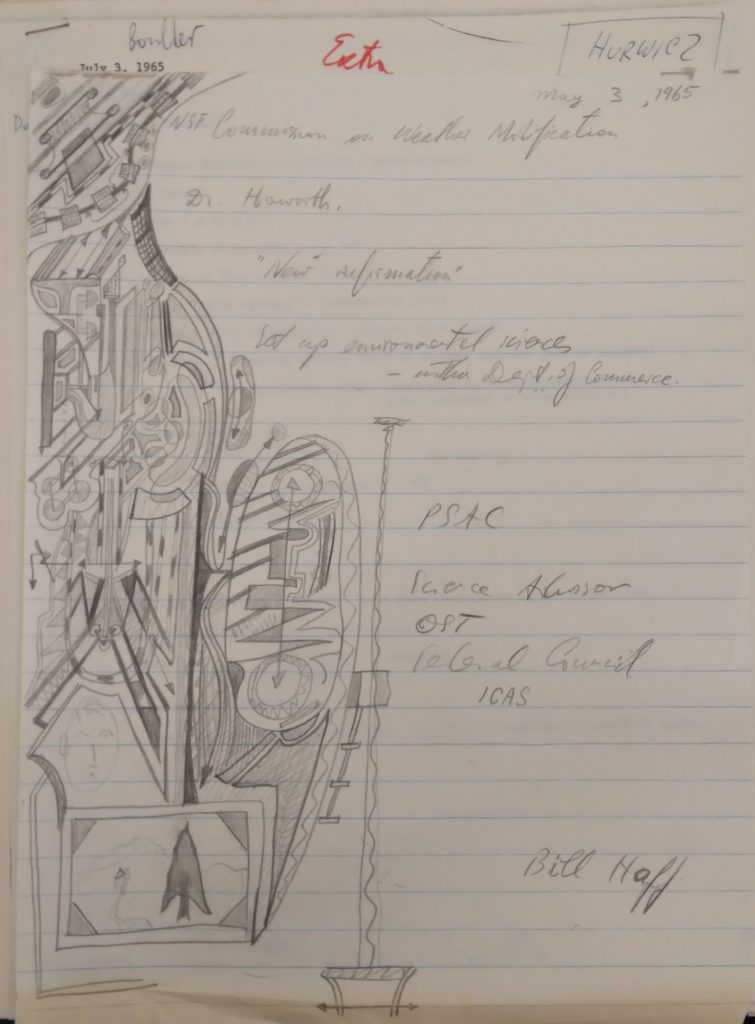

At one point in their correspondence, Samuelson asks Lange if he could name a few outstanding graduate students at Chicago, as he was looking for a new assistant. The first name on Lange’s list was that of Leonid Hurwicz, a young Polish immigrant who had arrived in Chicago at the beginning of the 1940s after fleeing Europe. Hurwicz became the assistant of Samuelson, now an Assistant Professor at MIT, in 1941, before coming back to Chicago to work in the Meteorology Department during the war. His papers, which I am currently reprocessing, trace his distinguished career at the University of Minnesota, where he stayed at for more than a half century after being recruited in 1951. For his creation of the field of mechanism design theory (the study of efficient allocation of resources), Hurwicz was jointly awarded the 2007 Nobel Prize at age 90.

In addition to Hurwicz’s correspondence and early manuscripts of his publications, I found in his papers the dissertation of Patinkin, which he annotated [this finding aid will be updated in September after reprocessing is completed]. Among Hurwicz’s many notes taken at seminars and conferences, one often finds more or less elaborate doodles—although the word doodle does not do justice to the intricacies of the abstract geometrical forms that are peppered throughout sixty years of thinking about economics!