Contributed by Amanda Mixon, PhD Candidate, Comparative Literature, University of California, Irvine. Read more in their recent article: Amanda Mixon (2019): “Not in my name”: the anti-racist praxis of Mab Segrest & Minnie Bruce Pratt, Journal of Lesbian Studies, DOI: 10.1080/10894160.2019.1678964

With the assistance of a Mary Lily Travel Grant, I visited the Sallie Bingham Center in the summer of 2018 to carry out research for my dissertation, which analyzes how a group of white southern lesbian writers theorize whiteness and practice anti-racist activism. The project is as much invested in tracing friendships and influences as it is in elaborating a single individual’s political thought. Therefore, when perusing the papers of Dorothy Allison (1949-), Minnie Bruce Pratt (1946-), and Mab Segrest (1949-), I was especially interested in how the holdings might give voice to these women’s relationships with each other and the two other figures in my study, Rita Mae Brown (1944-) and Lillian Smith (1897-1966).[i]

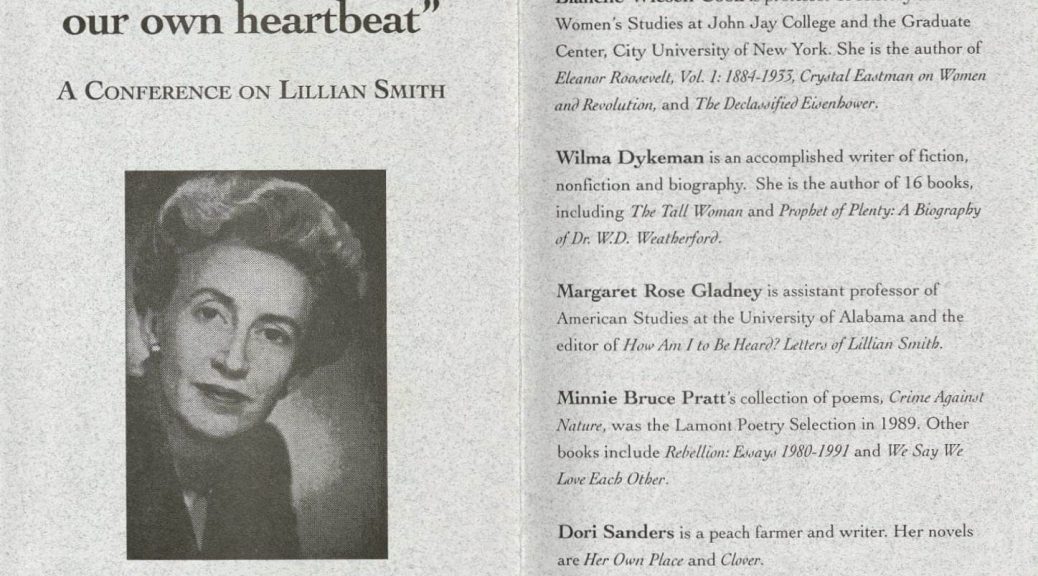

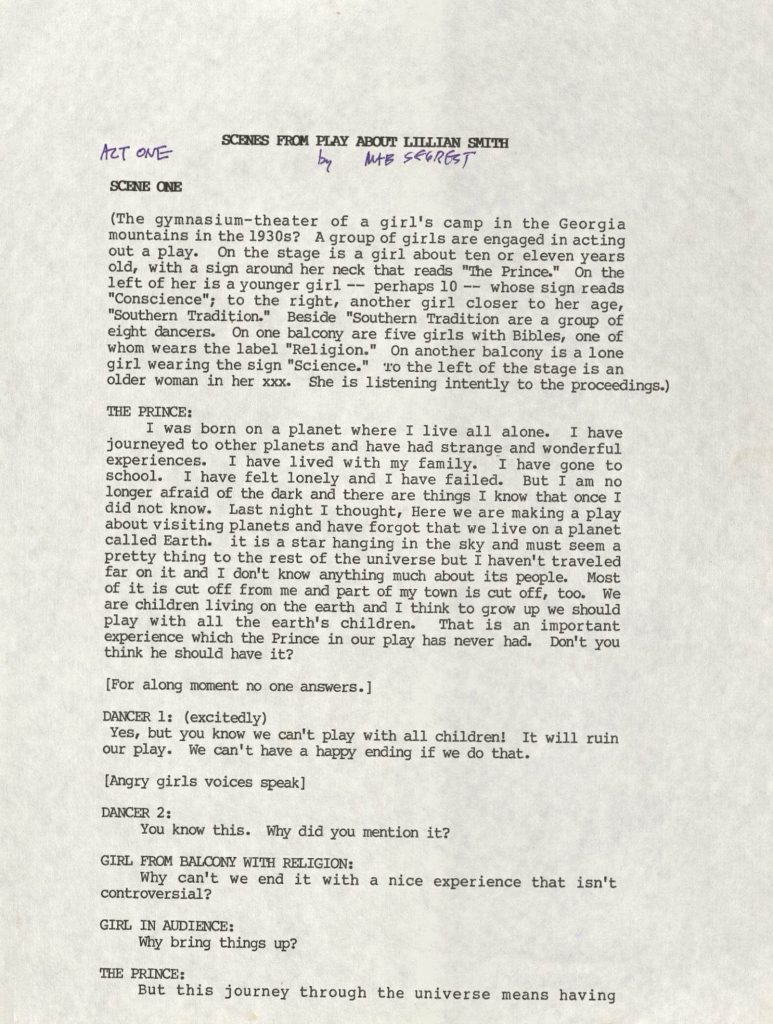

I knew that Smith, arguably the most outspoken white southern critic of Jim Crow segregation, had a profound impact on Pratt and Segrest. Her lifelong partnership with Paula Snelling (1899-1985) and searing critiques of white supremacy offered Pratt and Segrest a foundation from which to learn and build. However, when scanning Pratt’s papers, I was surprised to find an unpublished stage play that Segrest wrote about the couple in the late eighties. There, Segrest prioritizes Snelling’s experience, allowing her to criticize Smith for closeting their same-sex relationship. As Segrest told me in person, this centering is an ode to the significant amount of unrecognized work that Snelling contributed to Smith’s career and their collaborative projects. But what I found most compelling was Segrest’s creative license with the couple’s relationship: that is, no primary or secondary sources confirm the dynamic that Segrest depicts. As such, the untitled play is not only an example of how we represent historical figures in order to do them justice, but also an account of what those figures emotionally do for us. In their published nonfiction, both Segrest and Pratt express a yearning for a Smith not bound by the closet’s silence. In the play, Snelling becomes the voice of that desire. She asks: what would it have meant—for Smith’s own career and life, for Snelling, and for the countless women inspired by their work—if Smith had claimed a lesbian identity?

[i] Rita Mae Brown is author of the 1973 lesbian coming of age novel Rubyfruit Jungle. Lillian Smith was a white civil rights activist, known for her 1944 novel Strange Fruit, which featured an interracial couple.