Post contributed by Ashton Merck, Graduate Intern for the Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising, and Marketing History

In the mid-twentieth century, the Duke Power Company Home Service wished its customers a “Merry Christmas” and a “Happy New Year” with an annual collection of holiday recipes.

The John W. Hartman Center has at least two of these pamphlets in the Nicole di Bona Peterson Collection of Advertising Cookbooks. These cookbooks focused almost exclusively on holiday baking. One cookbook included separate sections for cakes, pies, candy, cookies, and desserts, while “salads, sandwiches, and breads” were combined into one category.

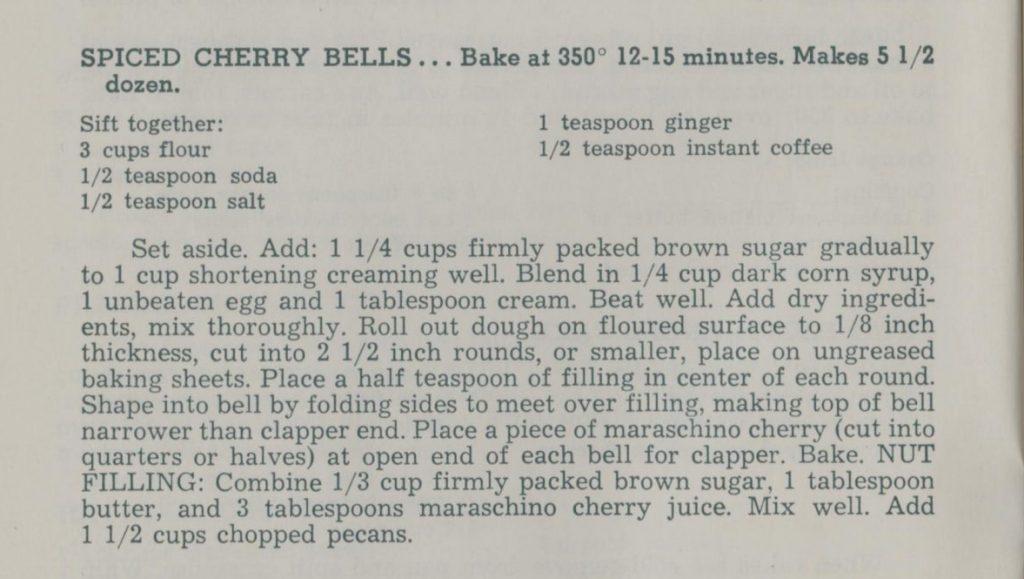

In the spirit of the holiday season, I decided that I would give one of these recipes a try. Quite a few of them looked recognizable as something my great-grandmothers used to make, like “Cheery Cherry Cake” or “Skillet Cookies.” Others, like a “Chocolate Yule Log” – which involved an unholy combination of mashed potatoes, confectioner’s sugar, and shredded coconut – sounded completely inedible. But one recipe, for “Spiced Cherry Bells,” caught my eye. Somewhat inexplicably, the recipe called for ginger and instant coffee, in lieu of the usual holiday spices like cinnamon, allspice, or nutmeg. It also required more advanced assembly than the other cookies or cakes, through the creation of the “bell” shape. It seemed like something that was unusual enough to be worth trying.

As soon as I mixed the dry ingredients, it was clear that there was not enough of either the ginger or the instant coffee to overcome the 3 ½ cups of flour called for in the recipe. I took note of that fact, but did not adjust the recipe for my taste, resisting the temptation to add copious amounts of cinnamon and nutmeg. I next realized that the ingredients as mixed was simply too crumbly to form a stable dough that I could roll out, even with the use of a stand mixer. I had to add about another 1/8 cup of heavy cream to get the dough to come together. Even still, it called for so much shortening that it was tricky to roll out to the thickness specified. I eventually managed to get the cookies onto the (mercifully, ungreased) cookie sheet, where I shaped them into something that, if you squint your eyes, could be imagined as “bells.” I then baked them for the allotted time of 15 minutes.

I considered what the small quantity of the “spices” might indicate about the time and place in which this recipe was created, and imagined several possible hypotheses: Perhaps instant coffee or ginger were expensive or hard to come by; or, the far more likely scenario, they were so ubiquitous that they might already be in the pantry anyway. That got me thinking – when was instant coffee invented? Could it have been a new or trendy product at the time?

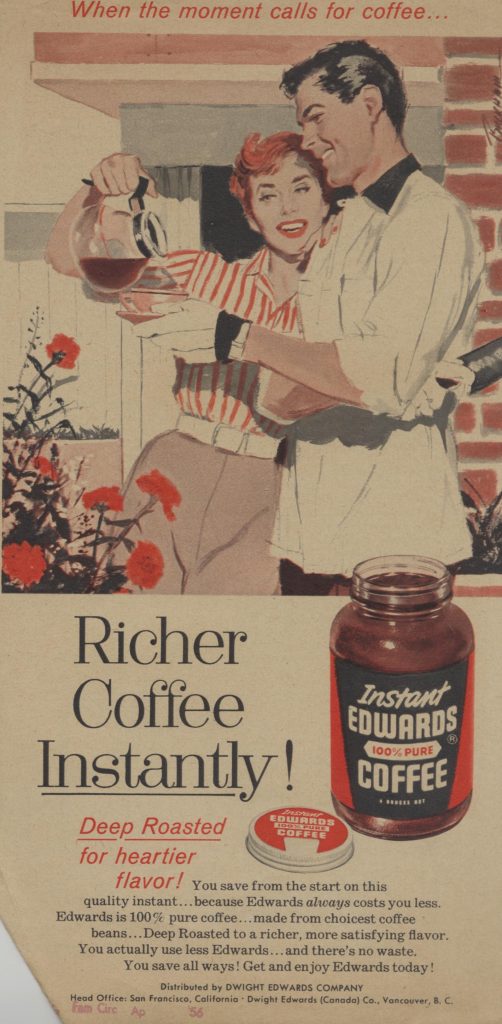

For an initial answer to these questions, I requested a box from the J. Walter Thompson “Competitive Advertisements” collection. The ads in the folders depicted instant coffee drinkers as married couples engaged in energetic outdoor activities or home improvement projects, like this campaign from 1956:

From looking at these ads, it seemed like instant coffee was one of many “convenience foods” that became tastier and more widely available in the post-WWII era, along with TV dinners and canned foods. I then requested another box from the Alvin Achenbaum collection, which contained several market research studies on coffee. The studies further emphasized that consumers valued instant coffee primarily for its convenience and low cost.

I also noticed that a few ads included recipes that contained small amounts of instant coffee, like this one for Swedish Beef Puffs at right.

But these ads were few and far between. As I perused the market research, I looked to see if the consultants recommended promotion of alternate uses of instant coffee in recipes, or baking, but they did not. Instead, the market researchers were far more interested in carefully segmenting the coffee buying market by their tastes and preferences, rather than by inventing new and creative uses for the product.

So, after this investigation – using Rubenstein collections, of course – it seems that instant coffee was already cheap and ubiquitous by the time it made it into the “Spiced Cherry Bells,” but the choice to use it in a recipe might have seemed as unusual then as it does now.

The Verdict: The cookies were … okay. The flavor of the baked, slightly caramelized maraschino cherry was delicious, and the “filling” mixture which called for pecans, brown sugar, and butter was something of a foolproof combination. But, as I expected, neither the instant coffee nor the ginger came through at all in the final bake.

Described by taste-testers as “aggressively neutral” and “a bit dry,” the dough was definitely the weak point in these cookies. “You almost get bored with it halfway through,” one observed. Yet the cookies also had a confusingly familiar flavor to them; there was plenty of room for the individual housewife to give the recipe her own spin enough to call it her own. As another taste tester noted, the recipe is “very much of the era.”

Love this! Thanks for the great combination of cooking and cultural history. I look forward to reading more.