Post contributed by David Romine, Rubenstein Library Technical Services intern and P.h.D . Candidate, Duke University Department of History

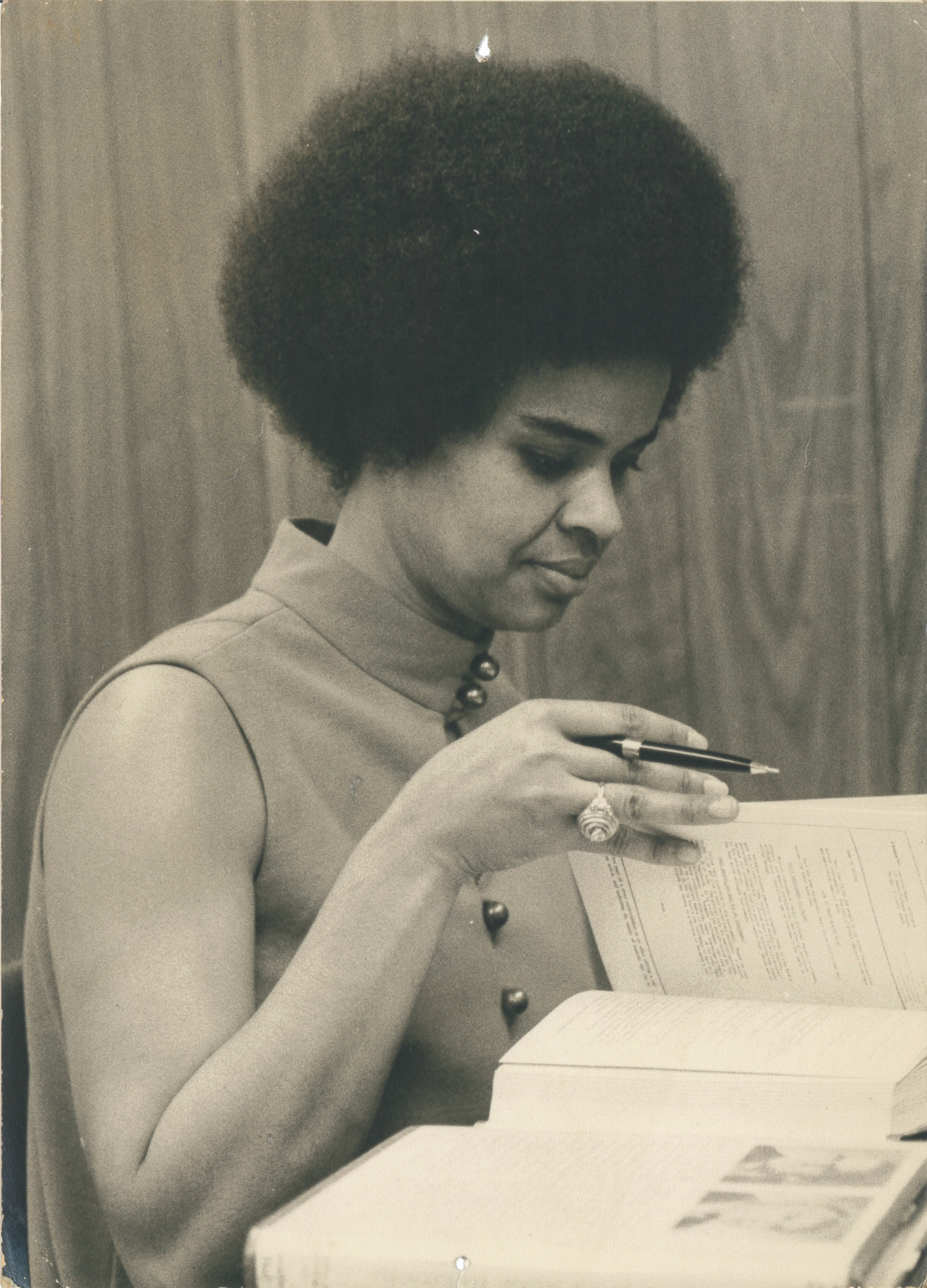

The story of how Florence Tate, a journalist from Dayton, Ohio, and a fixture in the city’s civil rights struggle, became active in African independence movements unfolds in her archive, recently processed and available for researchers at the Rubenstein Library at Duke.

Born in 1931, Florence Tate grew up in during an era when African Americans had already begun to see links between budding African liberation movements and domestic civil rights struggles. Honing her skills in mass communication and expanding her connections with Black reporters and government officials as the first Black female reporter for the Dayton Daily News, Tate also hosted young African exchange students in her home. Along with her husband Charles Tate, she was active in the Dayton chapter of the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), founded several local civil rights organizations including the women’s group Umoja, and was a tireless member of Friends of the Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). When the Coordinating Committee for the 1972 African Liberation Day invited her to participate as the national communications coordinator, she was able to put her skills to use on a national scale. While there had been other days that celebrated African liberation movements in the 1950s and 1960s, the 1972 African Liberation Day, held on Saturday, May 27, proved to be the largest in history and marked a sea change in African American activism.

Marches were scheduled for numerous American cities, including, Chicago and Pittsburgh, but the largest protest was to be held in Washington, DC. On the morning of the march, nearly 10,000 African Americans, some traveling from as far away as Houston, assembled in the Washington neighborhood of Columbia Heights where they set off on a long, snaking route to the National Mall. The marchers walked down Embassy Row and through Rock Creek Park, surprising many white citizens of the District as they loudly chanted, “We are an African People!” Among those leading the march was Queen Mother Audley Moore, a dedicated Black nationalist who had advocated for African independence movements since her days as a member of Marcus Garvey’s United Negro Improvement Association. At the end of the route, marchers listened to speeches at the Mall given by Imamu Amiri Baraka, Rep. Charles Diggs, and others who implored them to think of the “Black community” as greater than that of any one nation.

While much of Tate’s work on the march was behind the scenes, organizing and handling administrative details, and crafting press releases and other public statements, her role was nevertheless central to the national event. Two years later, during the Sixth Pan-African Congress (6PAC) held in Dar-es-Salaam, Tanzania, Tate traveled to Africa for the first time. Not only was she there in the capacity as a reporter, but she was also visiting her daughter, Geri, who was living in Tanzania at the time. It was at 6PAC that she came to meet several Angolan revolutionaries and, upon returning to the United States, began to devote more and more of her time to their cause. She founded several organizations to get the message of the Angolan liberation movement out to Americans and publicly advocated for those fighting the Portuguese government in African American political circles. These activities were not without controversy. Florence Tate threw her support behind the Union for the Total Independence of Angola (UNITA) at a time when many of her closest fellow activists, and her own daughter, supported the Popular Movement of the Liberation of Angola (MPLA), the group that went on to govern independent Angola.

As her archive reveals, Tate’s skillful use of official documents and opinion pieces increased American awareness of the conditions of the Angolan independence fighters. However, two of the groups she organized in Washington went further than op-eds and reportage. One of the first organizations she founded, Friends of Angola, organized a call for trained doctors, nurses, and other medical specialties to apply to be doctors in Angola. Another group, the African Services Bureau, publicized the plight of the Angolan groups fighting Portuguese rule. Having relocated to Washington, DC, she hosted dissident Angolan independence fighters on their visits to the United States, introducing them to diplomatic officials, writing press releases, and publishing op-eds in various American newspapers that were critical of the remaining colonial governments in Africa. Even as she served as the Press Secretary for Marion Barry’s first Mayoral Administration and later for Jesse Jackson’s 1984 presidential run, Tate remained focused on Angola throughout the 1980s.

While driven by the idea that the Black community extended beyond national boundaries, Tate’s archive reveals the ways in which she was also influenced by the personal connections and her on-the-ground experiences in Africa. Correspondence in her archive reflects the development of long-standing personal friendships and constant communication with Angolan revolutionaries and dissidents throughout the subsequent years of the Angolan Civil War, which did not end until the early 1990s. While other activists’ archives have documented the relationship between African Americans and the West African nations of Ghana, Nigeria, and Guinea, Tate’s archive is one of the first to offer insight into the freedom struggles in former Portuguese colonies, and bring to life in less-explored ways the links between the US Southern Freedom Movement and freedom movements in Southern Africa.