Welcome to the 1091 Project, a collaborative blogging endeavor between the conservation labs at Duke University Libraries and Iowa State Libraries. Today we are highlighting the kinds of training we do that supports the long-term preservation of our materials.

Welcome to the 1091 Project, a collaborative blogging endeavor between the conservation labs at Duke University Libraries and Iowa State Libraries. Today we are highlighting the kinds of training we do that supports the long-term preservation of our materials.

Care and Handling Training

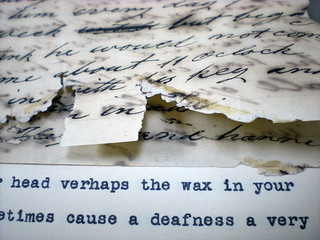

Conservation Services provides training in both informal and formal ways. We are often contacted by Technical Services for advice on proper handling or housing procedures for fragile materials. Sometimes we get a call from the reading room requesting our help to show a patron how to turn fragile pages or unfold brittle documents.

Conservation offers annual Care and Handling sessions for staff and student assistants. We usually offer multiple sessions in multiple locations to catch as many people as possible. For those unable to attend we put PDF’s of the handouts and Power Point slides on our intranet site (Duke NetID required).

In these sessions participants learn how to identify damaged materials and what the process is to send them to Conservation. We also demonstrate proper handling techniques such as shelving spine down, how to safely remove books from the shelf, and packing book trucks and mail bins for transport. Because of the current renovation projects we may not be able to offer on-site training this year. To that end, I’ve updated our handouts and Power Point presentations and will make sure student supervisors know where to find them.

New Directions

We are investigating the use of short videos as a fresh and fast way to get information to our patrons, staff and students. This is our first video in the series. What do you think? What sorts of videos would you want to see or show to your patrons?

httpv://youtu.be/8tyi86NE9sg

Other Training

We do a lot of other training, too:

- We participate in the disaster preparedness and recovery training sessions offered by the Preservation Department.

- We work with the staff in the Digital Production Center and the Internet Archives to make sure they are comfortable handling fragile materials during digitization. Sometimes we will actually help during imaging for particularly fragile or delicate items.

- We train our Conservation student assistants and volunteers on how to repair materials and make enclosures.We couldn’t be successful without them!

- We train ourselves, too. Each month before our staff meeting we hold a Tips Session. If we discover a neat tool, or come up with a creative solution to a problem, we demonstrate it to the entire lab staff. These session are fun, fast and foster a lot of conversation and brain storming.

Let’s go see what training Parks Library Preservation does. Please share your training regimen or ideas for videos in the comments.

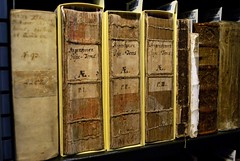

Creating enclosures is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. Very often you find yourself having to bring all your skills and experience to a project in order to create something to fit the project’s unique needs.

Creating enclosures is not a one-size-fits-all endeavor. Very often you find yourself having to bring all your skills and experience to a project in order to create something to fit the project’s unique needs.