One of my favorite aspects of my job is getting to closely examine books from our collection and learn more about how they have been used and maintained over time. A binding’s current condition or the way in which it has been repaired can tell you a lot about its value and use, but I am also very interested in the variety of the techniques or craftsmanship found in historical book repairs. The history of book repair is as long as the format has existed, and the level of proficiency can range from crude utilitarian (like this example) to a more subtle sophistication (such as our current standard of repair). We have shared examples of historical repairs from the collection before, but I found this next item to be very interesting in its execution and level of workmanship.

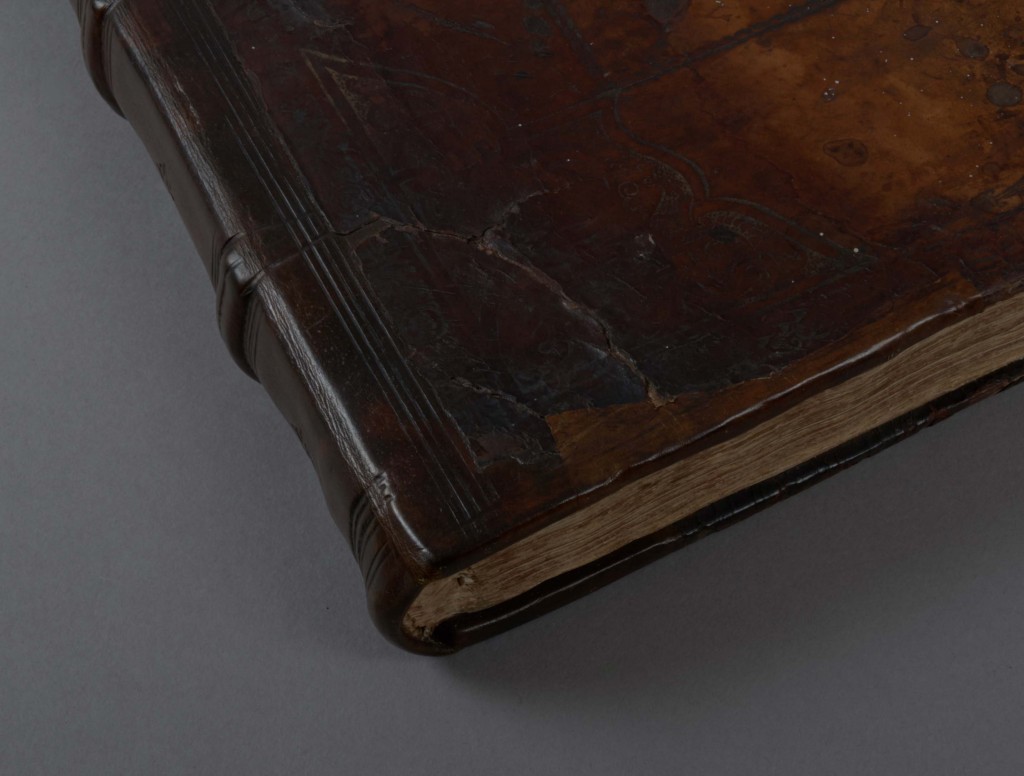

This 16th century atlas in a full calfskin binding has obviously been through a great deal and has been extensively repaired. The spine has been rebacked in dyed calfskin, the corners have all been repaired, and large areas of loss have been filled with new leather. I cannot say for certain when these repairs were done or even if they were all done at the same time, but suffice to say they are not recent. Several techniques have been used to blend the repairs with the original binding material and they are marginally successful in this regard. Click the photos below to enlarge.

New leather has been applied to the spine in the way of a typical reback: the original covering material has been lifted and new material has been adhered underneath. Nothing unusual there. The board corners and edges, however, have been repaired with onlays, or very thin pieces of calfskin adhered on top. Lines have been tooled in blind over the reback and onlays to continue the original decoration around the boards.

The fore-edge corner of the lower board has been repaired with a large inlay. Inlays are shaped pieces of leather of the same thickness as the original material, which fill the area of loss. My favorite part of this repair is the decoration which attempts to imitate the original floral patterns at the corners. The image below shows an intact original corner with decoration on the left and the decorated inlay on the right for comparison.

The binder who executed this repair did not have decorative rolls or stamps to match, so they just kind of made it up. The lines in this corner decoration are quite rough and shallow, which makes me think they were just drawn into the dampened leather, rather than actually impressed. Decorative rolls have been used around the outer edge of this corner, but they are quite different from the other decoration on the book. The binding has been heavily dressed, resulting in a very shiny surface to the leather.

It is apparent that a great deal of time and effort was put into this repair and it is successful insofar as it is still structurally sound and allows the book to function. We would approach treatment for a similar item very differently today, however.