The Story of Two Books

Jacob Dagger

The Writing of 444 Days: The Hostages Remember and Guests of the Ayatollah

In the spring of 2003, as many of journalist Mark Bowden’s reporter friends journeyed to Afghanistan to write about the progress of post-9/11 U.S. military initiatives or to Iraq to cover what would prove to be the last weeks of Saddam Hussein’s reign, Bowden had other plans.

Bowden, a national correspondent for The Atlantic Monthly, the author of the bestselling book Black Hawk Down, and a screenwriter on the blockbuster movie adaptation of that book, also hoped to travel to the Middle East to work on a story, but his destination was neither Afghanistan nor Iraq; to his colleagues’ surprise, he was instead headed to neighboring Iran.

Nearly three years earlier, at the urging of sources he had cultivated while writing Black Hawk Down, an account of a U.S. military mission in Mogadishu, Somalia, and Killing Pablo, about the hunt for Colombian drug kingpin Pablo Escobar, Bowden had begun work on a new project, a narrative of the 1979 Iranian hostage crisis. His sources, among them several men involved with Delta Force, the U.S. Army’s elite counterterrorism unit, believed they could give him unprecedented access to people and documents relating to the legendary unit’s first mission, a failed attempt to rescue the Americans who had been held hostage in Iran.

As Bowden began to read about the event, he realized that all of the books that had been published—personal narratives by former hostages, policy reviews by government officials, military histories—seemed incomplete, telling only small pieces of the story. He began to envision a book that would weave the various stories into a comprehensive account of the hostages’ 444-day ordeal, the rescue mission, and the political negotiations going on behind the scenes.

By 2003, Bowden was deep into the material. He had read all of the contemporary news articles detailing the crisis that he could find and had scoured memoirs written by former hostages. He had also begun tracking down former hostages and interviewing them about their experiences.

Early on, he had come across a copy of Tim Wells’s 444 Days: The Hostages Remember, a work of oral history published in 1985 that wove together passages from interviews with 27 former hostages. Bowden was amazed by both the number and depth of Wells’s interviews, but also curious about what might have been left on the editing room floor. For example, there was a series of interviews with Bill Daugherty, a CIA officer who was harshly interrogated for months by his captors. “If you look in Tim’s book, there might be five or six sentences taken from Bill Daugherty,” Bowden says. “I said to myself, ‘to get those five or six sentences, he must have done an extensive interview.'”

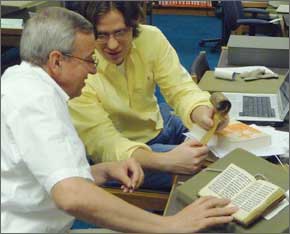

Bowden noted that Wells, a Duke alumnus, had donated his tapes and transcripts, along with other research materials, to the University’s Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library (RBMSCL). He scheduled a trip to Durham to see what else he might find in the Wells collection.

“It was like discovering hidden treasure,” Bowden recalls. “There were these long, involved interviews done with the hostages just a year or two after their release. Here I am tracking them down twenty years on, and here was the original stuff. Just an ocean of it.” He was especially pleased to find thorough interviews of hostages who had since passed away, or whom he had not been able to reach.

“I remember going to the woman who was working at the library there, telling her I wanted to copy the collection,” he says. Bowden pledged, when he was done with his own book, to donate his materials to the library so that they could sit alongside Wells’s for the convenience of future generations of researchers, a promise he followed through on soon after the publication of Guests of the Ayatollah in 2006.

Together, the Wells and Bowden collections represent a wealth of firsthand information about the hostage crisis—in the form of taped interviews and transcriptions, but also artifacts like personal letters and diaries. The materials provide a fascinating look not just into the minds of the hostages and their captors, but also into how the research process works. “If somebody wants to write a full and complete history of the [Jimmy] Carter presidency, I don’t think they’ll be able to do it without going through the Duke University library,” Tim Wells says. “Not just because of me, but because of Mark and other contributions along the way.”

The Iranian hostage crisis, which began thirty years ago this fall, was a pivotal event in Carter’s presidency. On November 4, 1979, a group of Iranian students scaled the walls of the United States embassy in the capital city of Tehran and took hostage some sixty staff members. Their initial intention, members of the group later said, was simply to stage a short but highly visible protest to inform the world of America’s crimes against their country—among them the 1953 CIA-led coup that ousted Iran’s democratically elected government, subsequent American support of Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi’s violent regime, and the U.S.’s decision in October to admit the deposed shah, whom Iranian revolutionaries wished to bring to trial and punish, ostensibly for cancer treatment.

But what began as a student protest was fed by the enthusiastic support of rioters across the city. Caught up in the moment, the Iranian students bound their captives, whom they suspected of spying, imprisoned them, and interrogated them. Motivated by revolutionary zeal and by what they saw as the will of the Ayatollah Khomeini, they combed the embassy—or “spy den,” as they called it—for paperwork that they believed would prove their worst suspicions about the U.S. When all was said and done, they would hold fifty-two of the hostages for 444 days, releasing them only after Carter, their perceived arch-enemy, was replaced after his first term by Ronald Reagan, whom they believed, incorrectly it turned out, would be more sympathetic to their plight.

As all this was going on, American media outlets had few facts to report, often relying instead on rumor and suspicion to fill their stories. Foreign diplomats were able to communicate, on and off, with three top U.S. officials who were held separately in the Iranian foreign ministry offices, and the hostage-takers staged a handful of media-friendly holiday “parties,” but for the most part, the hostages’ stories would not be told until after their release.

In January 1981, when the hostages were released, Tim Wells was just three-and-a-half years out of college, working as a paralegal for a Washington, DC, law firm. The hostage crisis, he recalls, “was one of the first major news stories in the world that I’d ever paid attention to.”

“The story ran for fourteen months, and then all of a sudden it was over, and everybody went home,” he says. “I thought it was one of the most intensely covered but virtually unknown stories ever to come along. Nobody really knew what happened to the hostages during those fourteen months other than the hostages and the terrorists.”

His curiosity was further piqued by a chance meeting with Bill Belk, a former hostage who had served as a state department communications and records officer in Tehran. Wells began to track down hostages to interview them about their experiences. Fortuitously, many of the former hostages, as state department employees, had remained in the Washington area, and Wells was able to find them fairly easily and without incurring much expense.

“Once I got through with the Washington people,” he says, “I had to travel, particularly to see the military folks. I was pulling a credit card out of my pocket and hoping I could get a book contract and pay it back. My girlfriend thought I was crazy.”

His enthusiasm paid off. After compiling several hundred pages of manuscript, in which he interspersed brief historical synopses with firsthand hostage accounts, he sent his unsolicited draft to an editor at Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Inc., whose work he admired; the editor purchased the book on the spot.

But as Mark Bowden would suspect years later, Wells’s 469-page book would represent just a fraction of the work Wells put into his interviews. Over the course of three years, he had talked to thirty-six of the former hostages, often speaking to the same person on multiple occasions. As he went, he typed up transcripts of the conversations, producing more than 5,000 pages of notes, all of which now reside at Duke’s Special Collections Library, along with his original tapes.

The first manila file folder in the Wells collection contains the yellowed transcript of an interview with Bill Gallegos, a 22-year-old marine guard at the time of the embassy takeover. The interview was completed on January 3, 1984, less than two years after his release:

“TIM: Can you give me a brief biographical sketch of what you were doing before you went to Tehran?

“BILL: I went to embassy school before I went to Tehran. Let’s see, I spent a year in Okinawa, Japan. And from there I went to Quantico, Virginia, to embassy school.”

As the conversation progresses, Wells asks his subject about whether he was aware of the risks he faced in Tehran: “Every place that I put on the dream sheet was a hot spot,” Gallegos replies, referring to the list of preferred assignments he submitted prior to receiving his posting. “So—I wanted to go—I’m adventurous I guess.”

Wells walks Gallegos and the other former hostages through their stories patiently, allowing them time to finish thoughts before asking for specific details that will help him, as an oral historian, to recreate the scene for readers.

Joe Hall, a military attaché, talks about the early days of captivity. “I mean I was really starting to feel gross. I hadn’t brushed my teeth. I hadn’t bathed. I was going on like four or five days in the same clothes by then. Hadn’t slept worth a darn….” “How about street noise at that time?” Wells asks.

The audio tapes of the interviews are fuzzy with age, but it’s intriguing the hear the former hostages’ voices coming through a quarter of a century later, calmly discussing their ordeal, at the time just a few years removed from the experience. Those are the words that Bowden heard when he visited the library to examine the Wells papers almost twenty years later.

Bowden’s research process was somewhat different than Wells’s. While Wells was primarily interested in collecting the firsthand accounts of the hostages, Bowden hoped to weave the hostages’ stories into a larger narrative. He began, with the help of a research assistant, by running a computer search and pulling all contemporary news articles that mentioned the crisis. At the Carter Center in Georgia, he found tapes of contemporary news broadcasts, which he had transcribed. He read every book he could get his hands on that dealt with the crisis.

Like Wells, he spoke to as many former hostages as he could locate, ultimately interviewing twenty-nine. But he also expanded the scope of his inquiry, tracking down several of the former hostage-takers, some of them who later served in government posts, to hear the other side of the story. His planned trip to Iran in 2003 was pushed back and then cancelled, but he did visit twice over the next two years, getting a feel for the rhythms of Tehran, and walking inside the old embassy.

In addition, he drew on his military contacts to learn about the failed rescue attempt—a topic that Wells had shied away from because it would have distracted him from the hostages’ story—and about roles played by the few CIA officers stationed at the embassy, information that Wells had not been able to pry loose at the time.

Bowden’s papers are revealing. The first five-and-a-half boxes, out of a total of nineteen, consist of bound news articles, drawn from an online database and organized by date. In the week after the crisis, there are 137 articles that discuss it. On January 19, 1981, the day before the hostages are released, there are 136.

Other boxes contain information about the rescue operation, a trial transcript from Roeder et al v. Iran, a class action suit filed by former hostages in U.S. court, a diplomatic chronology, and Xerox copies of several shredded and reassembled “spy den” documents, mostly innocuous files taken from the embassy by the Iranians and presented as evidence of U.S. spying.

There are six boxes of files on the hostages. For some hostages, there is little more than a typed and bound transcript, with lines numbered for easy reference. But for others, there are handwritten outlines and questions that Bowden has jotted down. There are things as mundane as Mapquest directions to former hostages’ houses alongside copies of more significant artifacts like diaries and letters written from captivity. Flipping through the files, you get a sense of the hugeness of the task Bowden faced in telling the story.

Bob Ode was a retired Foreign Service officer on temporary duty in Tehran when the students stormed the embassy. Among the items in his file is a copy of the Christmas card, dated “December 27, 1979, 54th Day,” that he sent to his wife a month and a half after later. There is also a letter he sent to Sen. John Warner.

Ode, who died in 1995, had compiled a calendar of significant events, such as his captors’ return of his wedding ring on December 16, the forty-third day of his captivity. His wife gave copies of the calendar and Ode’s 114-page diary to Bowden.

Bowden dedicates a great deal of attention to timelines, to figuring out who was where, when, and with whom. On the outside of Bill Belk’s file, Bowden has jotted out a brief outline of Belk’s movements around the embassy complex while in captivity, tracing his path from the staff cottages to the ambassador’s residence, to the “Mushroom Inn,” a warehouse basement (where he was kept with fellow hostage Malcolm Kalp), to solitary confinement after an attempted escape, to the chancery basement (he was held with Donald Hohman), to an upper floor of the chancery. In many of the folders are loose typed sheets, copies of Wells’s original interview transcripts, often with notes and follow-up questions scrawled in the margins in Bowden’s handwriting.

After Bowden’s visit to the RBMSCL, he contacted Wells, who is now the editor of the Washington, DC Bar Association’s Washington Lawyer magazine, to make sure that there were no copyright issues involved in the use of his transcripts. “I worried that since I was using his work in a sense, that he might feel some sense of ownership,” Bowden says. “He could not have been more generous about it. It was something he’d done a long time ago, and he’d moved on. If it could be of use to me, it was great.”

Learn More

- Tim Wells. 444 Days: The Hostages Remember. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985.

Also by Tim Wells:

- Drug Wars: An Oral History from the Trenches. New York: W. Morrow, 1992.

- Mark Bowden. Guests of the Ayatollah: The First Battle in America’s War with Militant Islam. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2006.

Also by Mark Bowden:

- The Best Game Ever: Giants vs. Colts, 1958, and the Birth of the Modern NFL. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2008.

- Black Hawk Down: A Story of Modern War. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 1999.

- Bringing the Heat. New York: Knopf: Distributed by Random House, 1994.

- Doctor Dealer: The Rise and Fall of an All-American Boy and His Multimillion-Dollar Cocaine Empire. New York: Warner Books, 1987.

- Finders Keepers: The Story of a Man Who Found $1 Million. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2002.

- Killing Pablo: The Hunt for the World’s Greatest Outlaw. New York: Atlantic Monthly Press, 2001.

Explore the Collections:

- Tim Wells Papers, 1982-1986. Papers comprise 546 audiocassette tapes, including masters, sub-masters, and use copies; 83 tape transcripts; signed release waivers and consent forms; magazine clippings; manuscript of 444 Days: The Hostages Remember.

- Mark Bowden Papers, circa 1979-2002. Transcripts of interviews with American hostages, Iranian hostage takers, and members of the military who were involved in the 1980 rescue attempt; bound news clippings

Further Reading:

- Stephen Kinzer. All the Shah’s Men: An American Coup and the Roots of Middle East Terror. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, 2003.

- Kinzer, Stephen. “Inside Iran’s Fury.” Smithsonian, October 2008, 60.

Recommended Viewing:

From 2005 to 2008 Jacob Dagger ’03 was Clay Felker Fellow and Staff Writer at Duke Magazine. He is currently working as a freelance writer in Berkeley, CA.