A Day for the Dead that Celebrates Life

A New Logo for the Duke University Libraries

Remembering a Special Friend of the Libraries

Collecting South African Photographs / Collecting South African History

During the Second World War, the Allies feared that German applications of science and technology were superior to their own and might be a determining factor in the outcome of the conflict. Consequently, as Allied troops secured German territory, British and American intelligence agents swept in behind them to gather information, specifically targeting the operations of industrial leaders like Bosch, Siemens, Agfa, Daimler-Benz, Krupp and Farben. The reports the agents prepared form an unusual collection of booklets that is part of the Duke University Libraries’ Special Collections Library.

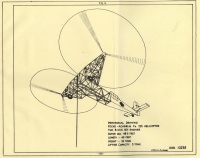

Duke’s collection is referred to as Science and Technology in Germany During the 1930’s and 1940’s. It includes over 3,000 individually titled reports on industries and technical applications that were of particular interest to the Allies, including armaments, communications, chemical warfare, aviation, naval technology, engineering, rubber production, the automobile industry, oil fields, synthetic fuels, rocketry and jet propulsion. The authors of the reports were civilian experts and military specialists, a cadre of some 12,000 investigators who submitted detailed descriptions, technical drawings, statistical reports, charts and graphs, and summaries of interrogations of German scientists.

Duke’s collection is referred to as Science and Technology in Germany During the 1930’s and 1940’s. It includes over 3,000 individually titled reports on industries and technical applications that were of particular interest to the Allies, including armaments, communications, chemical warfare, aviation, naval technology, engineering, rubber production, the automobile industry, oil fields, synthetic fuels, rocketry and jet propulsion. The authors of the reports were civilian experts and military specialists, a cadre of some 12,000 investigators who submitted detailed descriptions, technical drawings, statistical reports, charts and graphs, and summaries of interrogations of German scientists.

The reports are a rich resource for researchers interested in the economy of the Third Reich or the history of science around the time of the Second World War. Although many are related in some way to armaments, a host of other topics are also covered.  Autobahn (highway) bridges, woodworking machines in the furniture industry, public transport, photographic film, toys and dolls, dyestuffs and textiles, feathers, cork, leather, furs, pens and pencils, foodstuffs, rope, and twine are among the products and processes examined.

Autobahn (highway) bridges, woodworking machines in the furniture industry, public transport, photographic film, toys and dolls, dyestuffs and textiles, feathers, cork, leather, furs, pens and pencils, foodstuffs, rope, and twine are among the products and processes examined.

When the reports were published, they were made available to both industrial firms and the general public. Buyers, corporate and individual, tended to purchase only the reports that related to their area of interest. The Duke Libraries, on the other hand, acquired 2,858 reports in 1983 from British sources and a second lot of over 200 in 1990, making Duke’s extensive collection exceptional. The reports, researched from 1944-1947 and printed 1946-1949 in England, complement the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library’s large collection of Nazi imprints and help fill out a picture of this era for anyone studying the rise and the resources of the Third Reich.

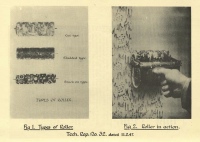

Quotes from “German Methods of Wall Decoration,” #876, which consists of reports on individual factories, recipes for wall covering mixes and paint removers, diagrams, photographs of rollers in action

Quotes from “German Methods of Wall Decoration,” #876, which consists of reports on individual factories, recipes for wall covering mixes and paint removers, diagrams, photographs of rollers in action

Artekobin Ges. Gerhard & Co. “Former premises and plant 100% destroyed and now carrying on in a small shed. The process of manufacture is confined to hand-punching small shapes of sponge rubber from sheet and to gumming the former individually on wooden roller. The process employed is laborious and primitive and compares unfavourably with the methods of other manufacturers referred to later in this report.”

Continentale Coutchouc & Guttapercha Werke, A.G. “…the largest Rubber Goods Manufacturers in Germany.” They make cylindrical coverings for Stippling Tools which “produce a large variety of wallpaper-like effects.” “We have seen a number of rooms attractively decorated by means of these Tools.”

From “German Activities in the French Aircraft Industry,” #610. “Object of their visit was to obtain information on all work done for the Germans by the principal French aircraft factories outside the Paris area during the occupation.”

The report covers aircraft design and production with description of the manufacture of individual parts and diagrams and photographs of planes, including Junkers. Some of the work was construction and repair, but it also covered designs and prototypes for new German aircraft. The French reported that at times, over their objections, the Germans transported all the machine tools and laborers out of a French factory and into Germany. The French, in one form of retaliation, reported that sabotage in the work they did for the Germans was “rife.” An example was putting emery powder into a graphite grease used in assembly, with “effective results.” The French got the emery powder from secret drops provided by the British Royal Air Force.

The Schacht Marie Salt Mine, Beendorf (Dispersal of Siemens, Berlin), #2388

The Schacht Marie Salt Mine, Beendorf (Dispersal of Siemens, Berlin), #2388

In order to move German industry away from bombing near Berlin, some went underground. This report is a 1945 investigation of the Siemens factory operations for the manufacture of aircraft instruments and autopilots, which went under cover in 1944. Investigators found the plant “in a disused salt mine at a depth of approximately 1200 feet. There are approximately 14 miles of tunnels and 150 main chambers of which 39 were planned to be used [for manufacturing].” Wiring had been installed and machinery moved in, but the plant had not yet gone into production when it was captured by American forces. It was “laid out for about 2000 men [employed] in two shifts,” and was within a month of being ready. At the time of its capture, there were “600 Germans and 400 foreigners” working there.

The remaining spaces in the mine were used for storage by the Luftwaffe. The Allies confiscated thousands of cases of parts for guns, photography equipment, raw silk and rigging for parachutes, airplane parts, bombsights, compasses, motors, and naval torpedoes.

Linda McCurdy, Head, Research Services, Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library and University Archives

This summer was contest time at The New York Times. The venerable (and, if circulation patterns hold, vulnerable) paper invited students to respond to Rick Perlstein’s, “What’s the Matter With College?” Author and historian Perlstein argues that college, as a discrete experience, has begun to disappear. In the late 1960s, college was a cultural obsession because, well, it was so countercultural.  No longer: The campus has become conventional, lured by the imperatives of entertainment, consumed by the values of marketing, and dedicated to producing investment bankers. “Just as the distance between the campus and the market has shrunk,” he writes, “so has the gap between childhood and college—and between college and the ‘Real World’ that follows.”

No longer: The campus has become conventional, lured by the imperatives of entertainment, consumed by the values of marketing, and dedicated to producing investment bankers. “Just as the distance between the campus and the market has shrunk,” he writes, “so has the gap between childhood and college—and between college and the ‘Real World’ that follows.”

Perlstein arrived at his conclusions after immersing himself in student conversations at the University of Chicago, which, twenty years ago, produced a scholar who pronounced an even harsher verdict on higher education. That was Allan Bloom, with The Closing of the American Mind. (The book’s pointed if somewhat ponderous subtitle is “How Higher Education Has Failed Democracy and Impoverished the Souls of Today’s Students.”) Bloom was a professor of philosophy and political science at Chicago; he was a translator and editor of Plato’s Republic and Rousseau’s Emile, both classic education tracts. Earlier in his career, he had taught at Cornell University—this during a time of student protests and building takeovers, unsettling episodes that he revisited in the book.

The Closing of the American Mind was a surprising sensation in the marketplace. A review in The New York Times hailed it as “essential reading for anyone concerned with the state of liberal education in this society.” Duke religion professor Kalman Bland observes that at the time the book appeared, at the height of the Reagan presidency, “bashing liberalism was fashionable. It also didn’t hurt sales that Saul Bellow’s prestigious name adorned the dust cover, announcing his foreword. It also didn’t hurt that Bloom gave voice to stodgy elders who were dismayed at the younger generation’s tastes in music and popular culture. A good inter-generational scold sells books, I suppose.”

Bloom himself, interviewed in The Chronicle of Higher Education, claimed he was “astonished” by “the favorableness of the response.” He added, “I thought my students and my small circle would have some interest in it…. Obviously, this was the right moment.”

Right moment or not, most readers, it’s easy to surmise, skipped over the lengthy discourse on European philosophical movements (with chapter headings like “The German Connection”). They were drawn, instead, to the opening section on students; there, the chapter on “Relationships” was divided into topics like “Self-Centeredness,” “Race,” and “Eros.”

Bloom conceived the book as “a meditation on the state of our souls, particularly those of the young, and their education.” He lamented what he saw as the decay of the humanities and the turning away from intellectual engagement—or from virtue—that resulted. “Today’s select students know so much less, are so much more cut off from the tradition, are so much slacker intellectually, that they make their predecessors look like prodigies of culture,” he wrote. Students arrive on campus “ignorant and cynical” about their political heritage, dispossessed of “respect for the Sacred,” and indifferent to the power of books as transmitters of tradition.

In Bloom’s view, youth culture—as expressed in its essence through the rawest of rock music—has drowned out any countervailing nourishment for the spirit. Young people have been conditioned, as it were, to see everything as conditional, or relative, whether the quality of books or the quality of relationships.

As Duke political scientist Michael Gillespie notes, the book was pounced upon by parents who saw their worst fears confirmed—that their children were out of control and that values-depleted campus environments would only foster more of the same. Gillespie taught at the University of Chicago and knew Bloom there. His older colleague, he observes, wasn’t convinced that democracy was good for breeding culture in young people (not that any other political system would be any better). As a scholar of Plato, Bloom was attuned to other transmission mechanisms. He wanted to channel erotic longing, which Plato identifies as a basic human impulse, into a longing for higher things. But as The Closing of the American Mind argued, the American campus had neglected that imperative as it abandoned the high-minded European intellectual tradition.

A sign of such abandonment, Bloom asserted, was a curriculum devoid of meaning, one that shied away from asking the questions that would elevate moral life. He said the humanities, in particular, suffer from “democratic society’s lack of respect for tradition and its emphasis on utility.”

Two years ago, The Chronicle of Higher Education looked at what has become a constant of the curriculum, literary theory. The article noted that theory has become entrenched in “the literary profession,” but that there’s no clear notion of what it means to be asking theoretical questions of a work of literature. One professor described the field as a free-for-all. “Theory has no material coherence, only an attitude,” he noted. Another professor was quoted as declaring that students “don’t have a background in literature because that isn’t anything that anyone thinks is of value anymore.” One can imagine the depths of Bloomian despair over such illustrations of intellectual fragmentation.

Just after the book was published, Duke Magazine brought together professors to ponder The Closing of the American Mind; the conversation was later edited for publication. Twenty years ago, in the faculty roundtable, Kalman Bland had this to say about Bloom: “He sees the university as an institution in society, and the function of the university in society as going against the grain. That’s the good part of the book—showing that the university does fit into the social context, and that it defines itself in relationship to the needs and values of that context. And the book asks us to take a close look at whether or not we’re serving the powers that be or whether we’re being the gadflies—the Socratic model of shaking our students up and liberating them from their popular biases.”

And what of the relationship now between campus culture and the wider culture? One answer comes in Louis Menand’s “Talk of the Town” essay in the May 21, 2007, issue of The New Yorker. Menand reported that the biggest undergraduate major by far today is business. Twenty-two percent of bachelor’s degrees are awarded in the field; less than four percent of college graduates major in English, and only two percent in history.

Looking at Duke today, Bloom might feel at once perplexed and vindicated, says Kalman Bland. From Registrar’s Office figures, Bland has found that the cohort of Duke students majoring and minoring in economics (648) exceeds the students majoring and minoring in philosophy(117) by almost 600 percent. “Perhaps, like many of us, Bloom would lament the practical pre-professionalism of so many of our students,” Bland says, and “be appalled at the miniscule number of majors and minors” in the traditional humanities. That relatively small numbers of students have chosen to major or minor in women’s studies or African and African American studies “would surely warm the cockles of his old-worldly, anti-liberal, anti-democratic, elitist, metaphysically-inclined, conservative heart.” (Bloom’s “vehement anti-feminism” had made “sexist patriarchy sound respectable,” Bland says.)

Bloom’s conservative heart helped shape a sort of literary genre, the higher-education critique. The Closing of the American Mind begat Charles Sykes’ 1988 Profscam: Professors and the Demise of Higher Education, which begat Roger Kimball’s 1990 Tenured Radicals: How Politics Has Corrupted Higher Education, which begat David Horowitz’s recent The Professors: The 101 Most Dangerous Academics. The genre is populated by screeds against professors and their presumed political agendas; Bloom had a wider focus, as does Perlstein, in his recent essay.

“If Perlstein wants a return to the ideals of an academy that is critical of the values of the larger society, the Bloom tradition aims at an embrace of traditional standards and norms,” says classical-studies professor Peter Burian, another participant in the original Duke Magazine conversation. “For Bloom, it was an issue that students were being assigned Toni Morrison rather than Plato, for Perlstein, that students mostly ignore both and the issues they raise.” Of course, if Perlstein’s lament rings true that college has lost its critical distance, then the so-called tenured radicals—concentrated as they are in the humanities—are marginalized. As Burian puts it, faculty members in areas like economics, business, engineering, and the sciences “have no problem with the disappearance of any distance—in terms of research funding and agendas and subjects taught—from the claims of the real world and its markets.”

Though it hardly had the marketplace success of The Closing of the American Mind, one book this summer aspired to a similar status as cultural critique. That was The Cult of the Amateur, by Andrew Keen, a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and writer. Considering such phenomena as Wikipedia, the blogosphere, and YouTube, Keen argues that the Web is threatening the very future of our cultural institutions. It’s all part of “the great seduction,” as he labels it—perhaps (or perhaps not) with a nod to Plato. The “revolution” unleashed by the Web, he writes, “has peddled the promise of bringing more truth to more people—more depth of information, more global perspective, more unbiased opinion from dispassionate observers.” In his view, this is all a smokescreen. What the revolution is really delivering is “superficial observations of the world around us rather than deep analysis, shrill opinion rather than considered judgment.”

For someone who decries a culture of shrillness, Keen can seem awfully shrill. But in a sense he’s illustrating the latest expression of what Bloom called democratic relativism. Twenty years after The Closing of the American Mind, we have cause to wonder if a culture with multiple seductions—real and virtual alike—can find an effective counterforce in the college experience.

Robert J. Bliwise is editor of Duke Magazine and an adjunct instructor in magazine journalism at Duke’s Terry Sanford Institute.

Robert J. Bliwise is editor of Duke Magazine and an adjunct instructor in magazine journalism at Duke’s Terry Sanford Institute.

Michael Bérubé. What’s Liberal About the Liberal Arts? New York: W.W. Norton, 2006.

Allan Bloom. The Closing of the American Mind. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1987.

Derek Bok. Our Underachieving Colleges. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2006.

Rachel Donadio. “Revisiting the Canon Wars.” The New York Times Book Review, Sept. 16, 2007.

Darryl J. Gless and Barbara Herrnstein Smith (eds.). The Politics of Liberal Education. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992.

Lawrence W. Levine. The Opening of the American Mind. Boston: Beacon Press, 1996.

Anne Matthews. Bright College Years. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997.

Bill Readings. The University in Ruins. Boston: Harvard University Press, 1996.

Henry Rosovsky. The University: An Owner’s Manual. New York: W.W. Norton, 1990.

Charles J. Sykes. ProfScam. Washington, D.C.: Regnery Gateway, 1988.

“Write what you know” is the standard advice to aspiring writers. But Professor Deborah Pope, who has guided the literary efforts of many Duke students, longed to find a way to push those enrolled in her “Writing and Memory” course to move beyond what they know and away from their usual creative voices. Muriel Rukeyser’s series of poems, “The Book of the Dead,” gave Professor Pope an idea. Horrified by the 1936 Union Carbide mining disaster in which many black workers contracted silicosis, the activist poet traveled to Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, to interview victims and their widows, listen to courtroom testimony, and examine documents related to the incident. The poems based on this material were published in U.S. 1 (1938). Pope decided to set her students a similar task: select a group of letters or a diary to serve as a springboard for a linked series of poems.

“Write what you know” is the standard advice to aspiring writers. But Professor Deborah Pope, who has guided the literary efforts of many Duke students, longed to find a way to push those enrolled in her “Writing and Memory” course to move beyond what they know and away from their usual creative voices. Muriel Rukeyser’s series of poems, “The Book of the Dead,” gave Professor Pope an idea. Horrified by the 1936 Union Carbide mining disaster in which many black workers contracted silicosis, the activist poet traveled to Gauley Bridge, West Virginia, to interview victims and their widows, listen to courtroom testimony, and examine documents related to the incident. The poems based on this material were published in U.S. 1 (1938). Pope decided to set her students a similar task: select a group of letters or a diary to serve as a springboard for a linked series of poems.

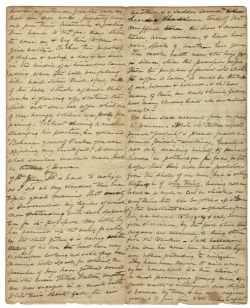

She turned to me for assistance in identifying materials that might inspire her students. Over a number of weeks, I assembled an annotated list of dozens of collections, grouped by topics such as “Civil War Hospitals,” “Teaching Freedmen,” “Union Organizing,” “Mental Illness,” “Love Letters,” and “World War I.” The class visited Perkins Library’s Mary Duke Biddle Rare Book Room where I introduced them to the protocols of using special collections and showed them letters, diaries, and photographs. During subsequent visits to the reading room, each student selected a collection and began the work of reading the texts and trying to understand their historical and emotional context.

Although the students were daunted initially by sometimes difficult handwriting, unfamiliar allusions, and fragmentary records, they were soon engaged. Katherine Lee Silk, for example, immersed herself in the Civil War-era papers of Lucy Muse Walton Fletcher, wife of a Presbyterian minister. Silk remarked, “I loved this project but it was definitely harder than I expected. Lucy Fletcher was such a great writer herself that many times I feared that whatever I wrote would not do her justice…What really impressed me about this project was my growing interest in it. I’m far from a history buff and so I thought that reading about the Civil War and such might bore me. It had quite the opposite effect. I felt that through reading Lucy’s papers American history came alive for me in a way that no textbook could give me. I wish that I could meet Lucy now that I seem to know her so well. I just hope that my poetry somehow conveys her feelings.” Silk’s poem, “Canvas Fleet, June 7th, 1865,” shows just how successful she was.

Canvas Fleet

June 7th, 1865We are what we learned as children.

Out of the window I watch my son

Playing with red and white canvas sails.

His very own fleet.A chorus of squeals

Another ship is down.

A stream of gutter waterA current of blood.

I hear the tone of drums

Down the street.

A profusion of flowers

Oh Bleeding hearts!I grasp their gaze,

Only the living gaze,

The strong survive.My husband’s head is bowed down.

His words echo

In my ear, my heart.“The battle rages but the war is won.”

The ripples still

As my son looks up.We are all children.

– Katherine Lee Silk

Adam Eaglin chose the papers of another woman who also reflected on the horrors of war.  Eaglin said, “The inspiration for the poem is from the Mary McMillan files—a collection of letters, published documents, and journals by Ms. McMillan, a Protestant missionary who lived in Hiroshima, Japan before and after the [atomic] bomb was dropped. Ms. McMillan’s collected documents tell the amazing story of her experiences in Japan, notable in her perspective as the first Protestant missionary allowed to return to Hiroshima after the disaster. I wrote a series of 3 poems from the documents; the second poem, ‘He cometh with clouds,’ is an imagined letter between Mary and another missionary during the period that she was forced to return to the U.S. The poem intends to capture the horrors of the Hiroshima disaster, and also to highlight Mary’s own anxiety as the war continued. Many of the details in the poem are real—borrowed from essays I found by the principal of the school at which Mary taught in Hiroshima. The principal was at the Hiroshima school the day the disaster occurred.”

Eaglin said, “The inspiration for the poem is from the Mary McMillan files—a collection of letters, published documents, and journals by Ms. McMillan, a Protestant missionary who lived in Hiroshima, Japan before and after the [atomic] bomb was dropped. Ms. McMillan’s collected documents tell the amazing story of her experiences in Japan, notable in her perspective as the first Protestant missionary allowed to return to Hiroshima after the disaster. I wrote a series of 3 poems from the documents; the second poem, ‘He cometh with clouds,’ is an imagined letter between Mary and another missionary during the period that she was forced to return to the U.S. The poem intends to capture the horrors of the Hiroshima disaster, and also to highlight Mary’s own anxiety as the war continued. Many of the details in the poem are real—borrowed from essays I found by the principal of the school at which Mary taught in Hiroshima. The principal was at the Hiroshima school the day the disaster occurred.”

He cometh with clouds

Today I refolded the sheets on my bed sixteen times.

They’re thin between my fingers, a pale-blue cotton,

when shaken, dust flies off the mahogany chests.

It’s cold for August—the glass on the windows

is kissed by ghosts, the color hanging like loose string.Do utensils still feel cold to the touch? I cannot eat.

I reach for the iron forks, but cannot bother to hold them.

I prefer to fumble with my chopsticks, the pair we bought

from the fisherman’s wife at Nishiki market. My fingers

wrap around them like coral, the way I hold this pen now.I write to stay awake. Even now my eyelids grow heavy.

(Promise not to laugh, Eleanor) but I’ve grown frightened of sleep,

there’s poison in my waking breath.

I will tell you of the dreams.Behold, He cometh with clouds, God said.

First there is brightness.

It swells like a purple tide within a cavern,

the splashing clamor of a thousand oceans,

the color grows so bright it dyes the earth white.

My eyes melt into my palms.Then silence, heavier than a mountain—only the voice of the Lord:

Every eye shall see Him, and they also which pierced Him:

and all kindreds of the earth shall wail because of Him.

Is it purgatory in which I find myself,

limbless, imprisoned

swept beneath a flood of fallen timbers?The vision vanishes. I stand atop the hill—

Miss Gaines’ tomb lying before me, and Hiroshima

in one splendid breath, beams beyond the monument.

Eleanor, you are there, beneath the hot Eastern sun,

picnicking with the young girls,

telling them how Miss Gaines founded their school.And when I saw Him, I fell at His feet as dead.

And He laid His right hand

upon me, saying unto me, Fear not;

I am the first and the last.

I realize some of the girls are crying. The body of a girl,

her uniform gone, lies beneath the shade of a cherry tree,

blossoms all around her.

There is another body by the grave.

With terror, I reach out to touch the girls,

they vanish in a flash of smoke.

I call for them by name, dozens of others,

there is an echo of “Miss Mary!” in the distance,

and then, nothing.They emerge from the black smoke as phantoms—

half the little children with eyes burned right out,

clothes singed against flesh.

I take them into my arms,

we all begin to sing,

“He leadeth me, by His own hand He leadeth me.”

One by one they collapse around me.

Silhouettes move around us like a song,

we huddle among the crowd of figures,

some red, others swollen and bleeding,

some without skin at all—only the stench of black flesh.

They are unrecognizable.

“Hai-i!” one calls in Japanese. It has the voice of child.

“Hai-i!” another, it is the sound

of my students, calling from within

or behind these swollen mounds,

I know not which. This is when I awake.“Hai-i” the sound echoes even now in my head like a curse.

Last night, the dream was different.

Again we sat before Miss Gaines’ tomb,

but the city was gone, blurred paint on a canvas,

the towers of buildings, a million faces—crushed into one.I know not what to make of these. Eleanor, please do not think me mad.

As I write this very letter

thick, black clouds gather in the west, concealed by night.

Late in the afternoon a curtain of shadow fell

across the stiff land beyond my bedroom window.

The image hangs in the corner of my eye, news of death,

yet still I pray they carry unseen hope on their sails.

Soon it will glide in through my window,

a Japanese lantern rocking gently on the ocean waves.Mary

– Adam Eaglin

“He cometh with clouds” earned Adam Eaglin the English Department’s 2007 Terry Welby Tyler, Jr. Award, which honors outstanding undergraduate poetry. Wanting to share the good news about the poem, I got in touch with Norma Taylor Mitchell, a friend of Mary McMillan who was instrumental in Duke’s acquisition of the papers. My news inspired her to telephone Mary’s sister, Jane Greenwood, in Mobile, Alabama. In the course of that conversation, Mitchell learned just how fortunate it was that the papers had been placed in Duke’s care: In 2004 the homes in the McMillan family compound in Milton, Florida, including the one where the papers had been stored, were nearly destroyed by Hurricane Ivan.

Like Adam Eaglin and Katherine Lee Silk, Tracy Gold also wrote about war. She used the letters of Frederick Trevenan Edwards and said of them, “While I found it hard to form poetry about the materials I read that was as inspired as the letters themselves, which were written beautifully, I loved reading the materials and becoming immersed in their world. Having access to the original copies of letters from WWI, an era that I was before connected to only through history class, made the lives of those who fought, and their families, so much more tangible. As I read each yellowing page, I found, in such a distant setting, emotions and thoughts that could have been my own friends’, or my own brother’s, making the story found in these letters even more real to me.” Her poem captures both Edwards’ sensitivity and the gritty horrors of World War I.

Eddie waits for orders by the cathedral

and dreams of the waters of Arcady Island;

these dreams have kept him punching

through French wilderness,

as he throws out each sock, gummy with mud,

as he catches an hour of sleep here or there, nothing more;

as the horses die on the roadside;

as reeking mounds of German corpses haunt the air,

chubby German girls smiling from their pockets;Old age in beautiful Arcady…

the childhood breeze

caressing his wrinkled face

while his grandchildren

play in peace…The dreams keep him wading through the mud

to the cathedral, where a shell exploding nearby,

punctures Eddie

9 times

in the chest.– Tracy Gold

Domestic tragedy skims the surface of Rayhaneh Sharif-Askay’s poem, which she drew from the papers of Reuben Dean Bowen. Bowen lived and worked in Paris, Texas, but his wife and only child, Adelaide, preferred the vibrant early twentieth-century New Orleans. Adelaide’s diaries are filled with accounts of parties and plays, but also reveal a dark side: marital discord, alcohol and drug abuse, and an early death. Rayhaneh Sharif-Askay’s “The Gulf Front at Galveston 1926” reflects the father’s melancholy thoughts at his beloved daughter’s decline.

Domestic tragedy skims the surface of Rayhaneh Sharif-Askay’s poem, which she drew from the papers of Reuben Dean Bowen. Bowen lived and worked in Paris, Texas, but his wife and only child, Adelaide, preferred the vibrant early twentieth-century New Orleans. Adelaide’s diaries are filled with accounts of parties and plays, but also reveal a dark side: marital discord, alcohol and drug abuse, and an early death. Rayhaneh Sharif-Askay’s “The Gulf Front at Galveston 1926” reflects the father’s melancholy thoughts at his beloved daughter’s decline.

The Gulf Front at Galveston 1926

The first condensed milk ever

was made in Galveston, its manufacture

transferred to New York State—at the time,

the greatest dairy state in the Union.

Like gasoline, they would ship the condensed milk

in bulk, drawing it off like molasses.

When I was a young boy,

my mother would send us

to retrieve the stuff in a tin bucket,

traipsing home we would hide ourselves

in an alley and dip our fingers in the sweet stuff,

eat as much of it as we dared to—without being caught.Now you never see it in bulk.

Neither you nor Mama would recognize

the Gulf front of Galveston now.

I remember the days when I would take you there

and you would play on the wet sand,

your letters traced there—as the tide stretched its formless slide

further each time—a promise

of your ever expanding slate,

A delineation to mark

where you would sink or stand—a flat grey plane.

You signed your name there, yet

after the waters foam and flood

your fluid canvas was clean again

I daresay there’s no question

Of what had kept the doctors away back then.

Perhaps now you’ve made markings you can’t rescind.

Will the shoreline absolve you again?– Rayhaneh Sharif-Askay

After the students had celebrated the end of the semester with a poetry reading and reception and Deborah Pope had graded their portfolios, she reflected on the success of the project. “This class has gone so splendidly and the poems emerging from the Special Collections have been so strong, have really provided a way to move the students out of their own default voices and concerns and into others’ experiences, into both public history and the lives of those who endured history but went unremembered, or just those who lived fascinating lives in their own personal, private way.”

In the end, then, the students did follow the “write what you know” advice. Yet, to do that, they had come to know and give voice to the thoughts and experiences of other writers from much different times and places.

Elizabeth Bramm Dunn is Research Services Librarian at the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library and University Archives

Elizabeth Bramm Dunn is Research Services Librarian at the Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library and University Archives

In response to a request from Elizabeth Dunn, students in Deborah Pope’s “Writing and Memory” class offer these poetry recommendations to the readers of Duke University Libraries.

Molly Knight recommends “any of the volumes by Ron Rash: Eureka Mill, Among the Believers, or Raising the Dead (I would pick Among the Believers if I had to choose one). He’s a NC-born poet who writes these beautiful, unsentimental little poems about poor, rural people in the Carolinas, past and present. Also a master of really subtle form-poetry.”

Melanie Garcia responds, “I like New and Selected Poems: Volume One by Mary Oliver and Staying Alive, an anthology.”

Adam Eaglin’s response: “One of my favorite volumes of poetry is Collected Poems by Sylvia Plath.”

Tracy Gold replies, “I recommend Alice Walker’s Horses Make a Landscape More Beautiful and anything by Octavio Paz.”

Katherine Lee Silk says, “one of my favorite anthologies is The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms by Mark Strand and Eavan Boland. I also enjoy reading the works of Elizabeth Bishop and T.S. Eliot.”

Neil Astley, editor. Staying Alive: Real Poems for Unreal Times. New York: Miramax Books, 2003. An anthology of five hundred contemporary poems explores themes of passion, spirituality, death, and friendship, in a collection that includes contributions by such writers as Mary Oliver, W. H. Auden, and Maya Angelou.

Elizabeth Bishop. The Complete Poems. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1969.

T.S. Eliot. Collected Poems, 1909-1965. New York: Harcourt, Brace & Co., 1991.

Mary Oliver. New and Selected Poems, Volume One. Boston: Beacon Press, 1992, 2005.

Octavio Paz. Eliot Weinberger, editor and translator. The Collected Poems of Octavio Paz, 1957-1987. New York : New Directions, 1987. Many other volumes of the poet’s work are available, in both the original Spanish and in English-language translations.

Sylvia Plath. The Collected Poems. New York: HarperPerennial, 1981, 1992.

Ron Rash. Eureka Mill. Corvallis, OR: Bench Press, 1998; 2001 reprint, Spartanburg, SC: Hub City Writers Project.

__ Among the Believers. Oak Ridge, TN: Iris Press, 2000.

__ Raising the Dead. Oak Ridge, TN: Iris Press, 2002.

Muriel Rukeyser. “Book of the Dead,” first published in U.S. 1. New York: Covici, Friede, 1938. In anthologies, including The Collected Poems of Muriel Rukeyser, edited by Janet E. Kaufman & Anne F. Herzog with Jan Heller Levi. Pittsburgh, PA: The University of Pittsburgh Press, 2005.

Mark Strand and Eavan Boland, editors. The Making of a Poem: A Norton Anthology of Poetic Forms. New York: Norton, 2000.

Alice Walker. Horses Make a Landscape Look More Beautiful: Poems. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1984.

Cartoon America: A Library of Congress Exhibition

http://www.loc.gov/exhibits/cartoonamerica/

From childhood, James Arthur Wood Jr. collected original cartoon art and then became an editorial cartoonist himself. He eventually donated his collection of over 36,000 original cartoon drawings to the Library of Congress. From that collection, 102 drawings reflecting Wood’s primary interests, including political illustrations, animation, and comic strips, have been chosen for this online exhibition. Among the many gems is a very fine crayon and ink political cartoon by Bill Maudlin that depicts Nikita Khrushchev berating a group of artists.

U.S. Congress Votes Database

http://projects.washingtonpost.com/congress/

With the momentum for the 2008 elections already building, this database created by the Washington Post encourages voters to learn more about their current legislators. The database draws on a variety of authoritative sources to provide a wealth of information, including voting and attendance records, financial disclosure statements, action on key votes, and roles in Congress. The site is updated daily.

Spices: Exotic Flavors and Medicines

http://unitproj.library.ucla.edu/biomed/spice/index.cfm

Since the first known use of spices 7,000 years ago in the Middle East, they have been employed for embalming, as ingredients in incense, as aphrodisiacs and medicine, and as flavorings for food. This informative Web site, created by the History and Special Collections Section of the Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library at UCLA, offers general facts about spices, including their sources and various uses, and a timeline. In addition, a separate page for each spice gives more details and a photograph of the processed and unprocessed form of the spice as well as a colored drawing of the plant and its parts from Bentley’s Medicinal Plants.

Since the first known use of spices 7,000 years ago in the Middle East, they have been employed for embalming, as ingredients in incense, as aphrodisiacs and medicine, and as flavorings for food. This informative Web site, created by the History and Special Collections Section of the Louise M. Darling Biomedical Library at UCLA, offers general facts about spices, including their sources and various uses, and a timeline. In addition, a separate page for each spice gives more details and a photograph of the processed and unprocessed form of the spice as well as a colored drawing of the plant and its parts from Bentley’s Medicinal Plants.

AskPhilosophers

http://www.amherst.edu/askphilosophers/

Have you ever wondered, “How long is forever?” or “What is the meaning of life?” To learn what philosophers have to say about these and many other topics, visit the “AskPhilosophers” Web site, where the dictum is “You ask. Philosophers answer.” A visitor to the site can ask a question, and if it hasn’t been answered in detail already, one of the participating scholar philosophers from around the world will respond fully in a few days. Visitors to the site can also browse previously answered questions through a subject list.

Thanks to the Internet Scout Project (Copyright Internet Scout Project, 1994-2007. http://scout.cs.wisc.edu/) for identifying all sites except for the spices site, which was recommended by Danette Pachtner, film, video, and digital media librarian at Duke. If you would like to recommend a Web site for inclusion in a future issue of Duke University Libraries, contact Joline Ezzell at joline.ezzell@duke.edu.

For the second year the Duke University Libraries and the Duke University Musical Instrument Collections are co-sponsoring Rare Music in the Rare Book Room, a series of monthly musical conversations and demonstrations. All events begin at 4:00pm on their respective dates and are held at Perkins Library in the Biddle Rare Book Room. For more information go to http://dumic.org/news_events.

October 19

October 19B. O’Neal Talton: From a Block of Wood to a Musical Instrument: An Introduction to Violin Making

Native North Carolinian Bob O’Neal Talton will talk about and demonstrate how he makes not only violins, but also violas, cellos, guitars, dulcimers, and banjos. There will be an opportunity for audience participation during the program when Bob invites musicians of all ages and abilities to try the instruments. Children are especially welcome to participate!

November 9

November 9Mamadou Diabate: A Griot and His Kora

Mamadou Diabate was born in 1975 in Kita, Malia. His name, Diabate, indicates that Mamadou comes from a family of griots, or jelis, as they are known among the Manding people. Jelis are more than just traditional musicians. They use music and sometimes oratory to preserve and sustain people’s consciousness of the past. Mamadou Diabate, joined by his son, will share the music and traditions of the Manding jelis in this kora demonstration. Please see Mamadou Diabate’s web site for more information about the two of them.

December 7

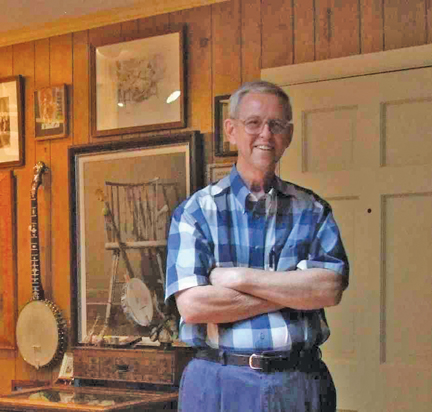

December 7William Michal Jr.: The Love of the Banjo

Dr. Bill Michal is a collector of outstanding banjos, specializing in those manufactured by Fairbanks. Using audio and slides, Dr. Michal will talk about the banjo’s history in America, particularly during the 19th and 20th centuries. The audience will hear recordings of banjo music, some made by Dr. Michal before he retired from public performance.

Neither Model nor Muse: A Symposium on Women and Artistic Expression

Neither Model nor Muse: A Symposium on Women and Artistic Expression

3rd biennial symposium of the Duke Libraries’ Sallie Bingham Center for Women’s History and Culture. Workshops, panels, and performance related to women and the arts. For more details, see the back cover of this magazine.

In an event that has become a Duke tradition, Reynolds Price, James B. Duke Professor of English, will once again read stories and poems for Halloween. The selections vary from year to year, but Edgar Allan Poe’s classic story “The Tell-Tale Heart” is almost certain to be on the program. Costumes welcome! Wednesday, 31 October, Lilly Library, Thomas Room, 7pm

The Library Presents Duke Moms and Dads

This annual program, held during Parents’ and Family Weekend, features a reading or talk by a writer who is also the parent of a first-year student. This year’s speaker is journalist Rome Hartman, former producer of the CBS Evening News. Hartman joined the BBC this year to develop and serve as executive producer of a BBC World News one-hour nightly newscast aimed at U.S. audiences. The title of his Duke talk is “Alphabet Soup: From CBS to BBC, some news about The News.” Saturday, 3 November, 11am, Perkins Library, Biddle Rare Book Room

Danny Wilcox Frazier, third recipient of the Center for Documentary Studies/

Honickman First Book Prize in Photography award for photographs of the changing face of the Iowa, will talk about his work and sign books at an opening reception (See “Exhibits,” page 5.). Thursday, 8 November, 5-7pm, Perkins Library, Biddle Rare Book Room

This summer Duke Libraries’ visual materials archivist and collector, Karen Glynn, traveled extensively in South Africa to support two documentary photography projects. One of the projects, “Then & Now,” is an exhibition of the work of 8 photographers. Each photographer submitted 20 prints; 10 prints made under apartheid and 10 prints post-apartheid. “Then & Now” opened at Rhodes University on 10 September. Conversations are underway at Rhodes and other institutions about establishing a South African Center for Documentary Studies, modeled after the Duke Center for Documentary Studies.

Glynn acquired a set of the 160 prints in the “Then & Now” exhibit for Duke’s Rare Book, Manuscript, and Special Collections Library. She also researched images for a future project entitled “Underexposed.” With South African photographer Paul Weinberg as her host and guide, Glynn moved around the country, meeting photographers and selecting work for “Underexposed.” This project proposes to scan 300 images by 13 South African documentary photographers, whose work is essentially inaccessible to the public, and mount the images on a webpage for educational, noncommercial use. In addition, two sets of 50 prints will be made of each body of work; one set will remain in South Africa, and one set will come to the Special Collections Library at Duke.

Contributions from the Duke Libraries’ John Hope Franklin Collection of African and African American Documentation and a Perkins Library funding grant supported Glynn’s acquisitions of the “Then & Now” and “Underexposed” images.

Excerpted from remarks University Librarian Deborah Jakubs delivered at a service to celebrate the life of John Richards (November 3, 1938-August 23, 2007). The service was held on 14 September 2007 at the Duke University Chapel.

John Richards wasted no time in becoming involved with the libraries at Duke. Barely a year after he came to the University in 1977 to become a member of the History Department faculty, President Terry Sanford invited him join the Library Council. John soon became chair, a position he would again hold in the mid-1990s; he served with enthusiasm over and over again. During the last year of his life, John served on the Executive Committee of the Friends of the Duke University Libraries.

John Richards wasted no time in becoming involved with the libraries at Duke. Barely a year after he came to the University in 1977 to become a member of the History Department faculty, President Terry Sanford invited him join the Library Council. John soon became chair, a position he would again hold in the mid-1990s; he served with enthusiasm over and over again. During the last year of his life, John served on the Executive Committee of the Friends of the Duke University Libraries.

John was warm, kind, and encouraging. When it came to the Libraries, he was all those things as well as passionate, insistent and bold. John was one of the most enlightened faculty at Duke regarding the advantages of online primary sources, and he worked hard to promote those investments. But he did believe in the critical importance of continuing to build collections, physical collections, of primary and secondary materials from around the world, and held firm to his conviction that the richness of collections in our libraries was essential to the work of faculty and students at Duke. He deeply appreciated the help of the library staff and respected them greatly. He championed the Libraries, and particularly the collections budget. For John, the library was to the humanist as the laboratory is to the scientist.

The relationship between a faculty member and a research librarian can be one of intellectual intimacy. Being engaged in a shared quest for the scholarship that will support an argument, confirm a suspicion, prove a hypothesis, or establish a thesis, creates a special bond, one John had with a number of librarians at Duke, including Avinash Maheshwary and Margaret Brill, in his work on South Asia and many related topics. He was also committed to collaboration in vernacular South Asian studies library collections within the Triangle Research Libraries Network (TRLN), encouraging broad collecting in all relevant languages of the sub-continent.

I am confident that John Richards will always hold the record for service on the Library Council. But, much more importantly, John will long live on in our noteworthy research collections, collections he helped to build, collections that will nourish the minds of generations of undergraduate and graduate students and serve as a solid foundation for future scholarship.

This summer the Libraries embarked on a logo redesign. The process began with an open meeting where library staff talked to representatives from Duke’s Office of Creative Services about what the new logo should convey about the Libraries. For an hour the Creative Services staff listened before leaving with a promise to synthesize the many ideas they had heard into fifteen to twenty preliminary designs. Working with Creative Services, we narrowed our choices in several stages until, after many conversations and revisions, one final design emerged.

The “mark” we chose, an open book form, with the Libraries supporting Duke University, represents content that the Duke University Libraries acquire, organize, and deliver to diverse audiences, and preserve for the use of future generations. The elongated right “arm” of the mark represents growth, forward movement, and change. The open book also represents the transfer of knowledge, which leads to the creation of new knowledge.

We have chosen this mark because books and libraries continue to be closely associated in the minds and hearts of people around the world. We embrace the myriad changes that technology is bringing to libraries, but, with this mark, we acknowledge the book as the foundation of all great library collections and the symbol of our role in connecting people + ideas.

The backbone of South America, the magnificent Andes mountain range, dramatically separates Chile and Argentina. Flying over the Andes is a stunning experience that inevitably evokes thoughts of Alive, the book and film about the true story of the tragic 1972 crash of the plane carrying the Uruguayan rugby team. Crossing the range via water, or “sailing the Andes,” is equally memorable, from an entirely different perspective. In March 2007, a group of Duke alumni and friends, ranging in age from 18 to 82, did just that, as part of a trip sponsored by Duke Alumni Education and Travel, a division of the Alumni Association (DAA). I had the great pleasure and privilege of serving as the “Faculty Lecturer” for this twelve-day, four-stop adventure, Chile and Argentina, with an Andean Lake Crossing.

Crossing the range via water, or “sailing the Andes,” is equally memorable, from an entirely different perspective. In March 2007, a group of Duke alumni and friends, ranging in age from 18 to 82, did just that, as part of a trip sponsored by Duke Alumni Education and Travel, a division of the Alumni Association (DAA). I had the great pleasure and privilege of serving as the “Faculty Lecturer” for this twelve-day, four-stop adventure, Chile and Argentina, with an Andean Lake Crossing.

The colorful, inviting brochures from Duke Alumni Education and Travel arrive periodically in our mail, and my husband, Jim Roberts (MBA ’85, P ’05), and I have fantasized about those tempting trips to exotic locales. Friends on the faculty at Duke have shared their experiences as Duke ambassadors on such adventures. I have been curious. I have been envious. As a former “Navy brat,” raised in no one particular place, I suffer (gladly!) from wanderlust. So when Rachel Davies, director of Alumni Education and Travel, inquired about my interest and availability for this trip, I barely took a breath before signing on the dotted line.

One role of the Duke host is to offer scholarly presentations on relevant topics during the trip. My background in Latin American history, with a focus on Argentina, made this assignment particularly appealing.  I developed a deep and abiding affection for Buenos Aires during the extended period I lived there while researching the social history of British immigrants and the development of their community during the 19th century for my Ph.D. dissertation. I try hard to return at least once a year to “BA,” one of the world’s greatest cities. Maybe it is nostalgia absorbed from all the tangos I have listened to over the years, but I feel reconnected with a part of my true self when I am in Buenos Aires.

I developed a deep and abiding affection for Buenos Aires during the extended period I lived there while researching the social history of British immigrants and the development of their community during the 19th century for my Ph.D. dissertation. I try hard to return at least once a year to “BA,” one of the world’s greatest cities. Maybe it is nostalgia absorbed from all the tangos I have listened to over the years, but I feel reconnected with a part of my true self when I am in Buenos Aires.

While living in Argentina, I traveled to many parts of the country, but never to Patagonia, which made this Duke trip even more appealing. An added attraction was that “El Grupo Duke” (pronounced “DU-que”), as we came to be known, included several present and past members of the Library Advisory Board, our most loyal and generous supporters and advocates, as well as many new friends. We were a remarkably compatible group of eighteen, and by the end of our twelve days together we were genuinely sorry to have to go our separate ways.

Our adventure began in our respective departure cities as, two by two, we gradually met up with fellow travelers. Many of us became acquainted in the airport lounge in Miami, after spotting the tell-tale orange luggage tags supplied by the Duke Alumni Association and introducing ourselves before boarding the overnight flight to Santiago. There, at the airport in the early morning, we travelers converged as our flights arrived in close succession. We were met by Pedro Porqueras, our fantastic tour director, who would accompany us on the entire trip, taking care of every possible logistical detail, and Rodrigo, our local tour guide for the city of Santiago. The logistics for our trip were handled seamlessly, making it easy for us to relax and enjoy ourselves. The eight-hour overnight flight was long, but because it was north-to-south, with only one time-zone change, the jet lag was minimal and we spent a good part of the day sightseeing. At that evening’s welcome dinner at our hotel, we enjoyed superb Chilean seafood and began serious bonding as, in turn, we introduced ourselves and shared our reasons for being there. The conviviality of that evening characterized the rest of the trip.

Our adventure began in our respective departure cities as, two by two, we gradually met up with fellow travelers. Many of us became acquainted in the airport lounge in Miami, after spotting the tell-tale orange luggage tags supplied by the Duke Alumni Association and introducing ourselves before boarding the overnight flight to Santiago. There, at the airport in the early morning, we travelers converged as our flights arrived in close succession. We were met by Pedro Porqueras, our fantastic tour director, who would accompany us on the entire trip, taking care of every possible logistical detail, and Rodrigo, our local tour guide for the city of Santiago. The logistics for our trip were handled seamlessly, making it easy for us to relax and enjoy ourselves. The eight-hour overnight flight was long, but because it was north-to-south, with only one time-zone change, the jet lag was minimal and we spent a good part of the day sightseeing. At that evening’s welcome dinner at our hotel, we enjoyed superb Chilean seafood and began serious bonding as, in turn, we introduced ourselves and shared our reasons for being there. The conviviality of that evening characterized the rest of the trip.

We toured the lovely city of Santiago, visited La Moneda, the presidential palace where President Salvador Allende lost his life in the military coup of 1973 (the other September 11), the Palacio Cousiño, a 19th century mansion, the pre-Columbian museum, the Santa Rita Winery, and La Chascona, one of Nobel Prize-winning writer Pablo Neruda’s houses, with its unique design and whimsical touches. On our third day, we flew two hours south to the busy fishing port of Puerto Montt, where we met Marcel, our highly entertaining local guide for the south of Chile, an avid fan of Edgar Allan Poe!

He and Pedro took us to the local outdoor fish and produce market, where they spontaneously created a scavenger hunt: they assigned us to small groups, armed each with a five-peso note and a slip of paper bearing the name of a different item the group was to locate at the market, and gave us limited time in which to complete our quest, return to the group, and share our discoveries. One group’s “catch” was a very large piece of kelp; my partners and I found a choro maltén, a local clam; another group displayed its bag of merquén, a spice common to the region – and so on. The whole experience was both enlightening and entertaining. By the time we boarded the bus for Puerto Varas, our next stop, we were becoming fast friends.

My presentation to the group that evening, on the political, economic, and social history of Chile and Argentina, stimulated a lively discussion that created even more connections among group members.  Chile, one of the oldest democracies in America, has nevertheless experienced dark times, most recently the 1973-1989 period of military rule. Opinion is still sharply divided on the legacy of General Augusto Pinochet. Chile’s current president, Michele Bachelet, a pediatrician, epidemiologist, and torture survivor, is the first woman president of the country. She succeeded Ricardo Lagos, who earned his Ph.D. in economics at Duke University. Chile boasts two Nobel laureates in literature, Gabriela Mistral (the first woman to be given this honor, in 1945), and Pablo Neruda. Another well-known naturalized Chilean writer (born in Argentina) is Duke’s own Ariel Dorfman, author of Death and the Maiden and many works of poetry, prose, and essays, and a popular professor. Argentina, a country richly endowed with natural resources of all kinds and populated largely by European immigrants, has endured economic crises and political upheaval, due in part to the powerful legacy of peronismo. Juan Domingo Perón and his wife Evita, now a cult figure who is either beloved or deeply resented, set the country’s course in the mid-twentieth century. The “Dirty War” and tragic years of military dictatorship (1976-83), during which thousands of people were “disappeared,” was a dark chapter from which Argentina is now emerging.

Chile, one of the oldest democracies in America, has nevertheless experienced dark times, most recently the 1973-1989 period of military rule. Opinion is still sharply divided on the legacy of General Augusto Pinochet. Chile’s current president, Michele Bachelet, a pediatrician, epidemiologist, and torture survivor, is the first woman president of the country. She succeeded Ricardo Lagos, who earned his Ph.D. in economics at Duke University. Chile boasts two Nobel laureates in literature, Gabriela Mistral (the first woman to be given this honor, in 1945), and Pablo Neruda. Another well-known naturalized Chilean writer (born in Argentina) is Duke’s own Ariel Dorfman, author of Death and the Maiden and many works of poetry, prose, and essays, and a popular professor. Argentina, a country richly endowed with natural resources of all kinds and populated largely by European immigrants, has endured economic crises and political upheaval, due in part to the powerful legacy of peronismo. Juan Domingo Perón and his wife Evita, now a cult figure who is either beloved or deeply resented, set the country’s course in the mid-twentieth century. The “Dirty War” and tragic years of military dictatorship (1976-83), during which thousands of people were “disappeared,” was a dark chapter from which Argentina is now emerging.

Our two days and nights in Chile’s Lake District, on the shore of Lago Llanquihue (yan-KEE-way), were filled with fascinating sightseeing and breathtaking scenery, including snow-capped volcanoes Osorno and Calbuco just across the lake from our hotel.  We lunched at the German Club and visited Frutillar, site of the Museum of German Colonization, with its educational exhibits displaying the way of life of immigrants to the region in the 1800s. Marcel served up rich historical detail to us on the bus as we moved from place to place, passing a salmon farm, notable Bavarian-style architecture, and more stunning scenery. El Grupo Duke took advantage of the “photo ops” along the way.

We lunched at the German Club and visited Frutillar, site of the Museum of German Colonization, with its educational exhibits displaying the way of life of immigrants to the region in the 1800s. Marcel served up rich historical detail to us on the bus as we moved from place to place, passing a salmon farm, notable Bavarian-style architecture, and more stunning scenery. El Grupo Duke took advantage of the “photo ops” along the way.

We awoke on the fifth morning in Chile with great anticipation: it was the day we would “sail the Andes.” On the way we visited Petrohué Falls, with its unusual volcanic rock formations and emerald-green waterfalls. We crossed Lago Todos los Santos via catamaran and, after lunch in Peulla, boarded another ferry for the crossing of Lago Frias and Lago Nahuel Huapi. From the deck of the boat one of our Grupo fed the gulls as they swooped down to take pieces of bread from his hand. The weather was perfect, and we had striking views of the spectacular scenery. It is impossible to capture in words the lake region’s breathtaking beauty and peace, which became even more evident as we arrived at our next stop, the Hotel Llao Llao, on the Argentine side of the Andes, in San Carlos de Bariloche. There we met Elizabeth, also known as “Mausi” (a family nickname), our delightful and very knowledgeable local guide.

Bariloche, the gateway to Argentine Patagonia, is an elegant Swiss-style city, known for its fine chocolate, shopping, ski resorts, exceptional natural beauty and outdoor recreation. St. Bernard dogs are the city’s mascots, hanging out with their owners (and available for photos) on city plazas and at scenic spots. Mausi and Pedro accompanied us to the Cerro Campanario, where we rode the chair lifts up to the very top of the mountain for a spectacular view of the many lakes and fjords that characterize the region. The Hotel Llao Llao (pronounced “zhao-zhao”), which once served as the park lodge, overlooks the Nahuel Huapi National Park, the first national park in South America, created in 1934. The hotel’s name derives, as do many terms in the region, from the Mapuche language and translates roughly as “very good.” Because the language contains no word for “very,” repeating a word adds that emphasis. To El Grupo Duke, it was so lovely that it might have been “Llao Llao Llao,” a place to which we all plan to return. But Buenos Aires beckoned, so we bade farewell to Patagonia.

Bariloche, the gateway to Argentine Patagonia, is an elegant Swiss-style city, known for its fine chocolate, shopping, ski resorts, exceptional natural beauty and outdoor recreation. St. Bernard dogs are the city’s mascots, hanging out with their owners (and available for photos) on city plazas and at scenic spots. Mausi and Pedro accompanied us to the Cerro Campanario, where we rode the chair lifts up to the very top of the mountain for a spectacular view of the many lakes and fjords that characterize the region. The Hotel Llao Llao (pronounced “zhao-zhao”), which once served as the park lodge, overlooks the Nahuel Huapi National Park, the first national park in South America, created in 1934. The hotel’s name derives, as do many terms in the region, from the Mapuche language and translates roughly as “very good.” Because the language contains no word for “very,” repeating a word adds that emphasis. To El Grupo Duke, it was so lovely that it might have been “Llao Llao Llao,” a place to which we all plan to return. But Buenos Aires beckoned, so we bade farewell to Patagonia.

We made the most of our four days in Buenos Aires, thanks to Pedro, himself a porteño (as natives of the port city of BA are known). His encyclopedic knowledge of history, economics, sports, politics, flora and fauna enriched our experience tremendously. We stayed in the fashionable Recoleta neighborhood, and visited the Recoleta Cemetery, a veritable “city of the dead” with its ornate mausoleums, the resting place of Argentine elites, national heroes, writers and poets, as well as Evita Perón herself. Our city tour took us to the Casa Rosada, presidential palace, the National Cathedral, the San Telmo antiques market, and La Boca neighborhood, birthplace of tango and home during the 19th and early 20th centuries to the waves of Italian, French, and Spanish immigrants who populated the port, a time when three-quarters of the adult male population of the city was foreign-born. That stroll back in time, and my presentation on the evolution and social history of tango, along with musical illustrations, whetted our appetite for the tango show that had us riveted one evening. The dancers were superb, and the host, a Carlos Gardel impersonator, was uncanny in his resemblance to the late legendary tango singer.

Our all-day excursion to an estancia on the pampas, El Rosario de Areco, gave the group the chance to consume a multi-course, typical asado or barbecue as well as to see a demonstration of the skills on horseback of the gauchos who work on the ranch. In addition to its delectable beef and fine wines and, of course, tango, Argentina is well known for the superior quality of its polo players and polo ponies, a focus of El Rosario de Areco and our gracious hosts there, Pancho and Florencia Guevara. Three of their nine children are professional polo players, in England! That evening, back at our hotel in Buenos Aires, El Grupo Duke hosted a reception for alumni and friends of Duke, members of the Duke Club of Argentina. It was the first time a DAA trip and a local alumni event had been combined and seems to have been a great success, attended by 30-40 new Duke friends, many of whom had also been at an event hosted by Duke’s former president Nan Keohane on her 2001 trip to Argentina, Chile and Brazil to meet friends of Duke, a trip I was fortunate to have been on as well.

Our all-day excursion to an estancia on the pampas, El Rosario de Areco, gave the group the chance to consume a multi-course, typical asado or barbecue as well as to see a demonstration of the skills on horseback of the gauchos who work on the ranch. In addition to its delectable beef and fine wines and, of course, tango, Argentina is well known for the superior quality of its polo players and polo ponies, a focus of El Rosario de Areco and our gracious hosts there, Pancho and Florencia Guevara. Three of their nine children are professional polo players, in England! That evening, back at our hotel in Buenos Aires, El Grupo Duke hosted a reception for alumni and friends of Duke, members of the Duke Club of Argentina. It was the first time a DAA trip and a local alumni event had been combined and seems to have been a great success, attended by 30-40 new Duke friends, many of whom had also been at an event hosted by Duke’s former president Nan Keohane on her 2001 trip to Argentina, Chile and Brazil to meet friends of Duke, a trip I was fortunate to have been on as well.

On our final evening in BA, before we all went out for the typical post-10 p.m. dinner of tender beef or exquisite pasta, my husband Jim gave a lecture on the history of the wine cultures of Chile and Argentina, illustrated with a wine tasting. Jim is Duke’s executive vice provost for finance and administration and, as an adjunct professor in the History Department, teaches about the social history of alcohol from a comparative perspective. The program was a fitting end to our gastronomic and oenophilic adventures, as we reluctantly anticipated our return to the United States.

A trip such as this, in which strangers come together for nearly two weeks of close companionship, united at first solely by their desire to visit and learn about another part of the world, can be a hit-or-miss experience. As our trip drew to a close, I felt very fortunate to have shared these good times with such warm, witty, smart and adventurous people, whom I now count among my friends. Because of our common Duke connection, I know there is a good chance I will see them again. In the meantime, we will carry our memories with us, and look forward to El Grupo Duke: The Sequel!

Deborah Jakubs is Rita DiGiallonardo Holloway University Librarian, Vice Provost for Library Affairs and Adjunct Associate Professor of History at Duke University. She is pictured with her husband, Jim Roberts.

Deborah Jakubs is Rita DiGiallonardo Holloway University Librarian, Vice Provost for Library Affairs and Adjunct Associate Professor of History at Duke University. She is pictured with her husband, Jim Roberts.

credit: Photos by Jim Roberts and Pedro Porqueras