Life in Duke University Libraries has been even more energetic than usual these past months. Our neighbors in Rubenstein just opened their newly renovated library and the semester is off with a bang. As you can read over on Devil’s Tale, a lot of effort went on behind the scenes to get that sparkly new building ready for the public. In following that theme, today I am sharing some thoughts on how producing digital collections both blesses and curses my perspective on our finished products.

When I write a Bitstreams post, I look for ideas in my calendar and to-do list to find news and projects to share. This week I considered writing about “Ben”, those prints/negs/spreadsheets, and some resurrected proposals I’ve been fostering (don’t worry, these labels shouldn’t make sense to you). I also turned to my list of favorite items in our digital collections; these are items I find particularly evocative and inspiring. While reviewing my favorites with my possible topics in mind (Ben, prints/negs/spreadsheets, etc), I was struck by how differently patrons and researchers must relate to Duke Digital Collections than I do. Where they see a polished finished product, I see the result of a series of complicated tasks I both adore and would sometimes prefer to disregard.

Let me back up and say that my first experience with Duke digital collections projects isn’t always about content or proper names. Someone comes to me with an idea and of course I want to know about the significance of the content, but from there I need to know what format? How many items? Is the collection processed? What kind of descriptive data is available? Do you have a student to loan me? My mind starts spinning with logistics logistics logistics. These details take on a life of their own separate from the significant content at hand. As a project takes off, I come to know a collection by its details, the web of relationships I build to complete the project, and the occasional nickname. Lets look at a few examples.

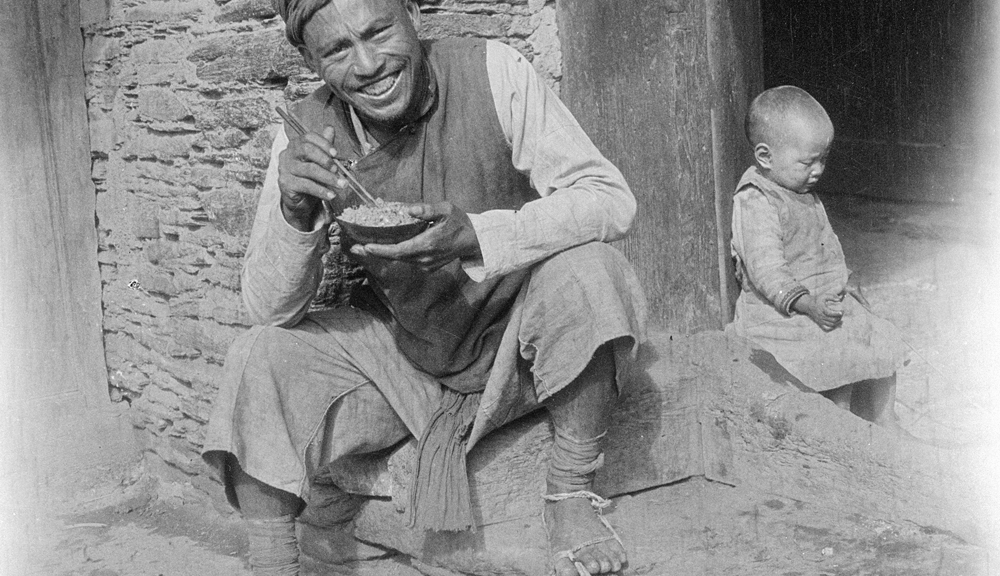

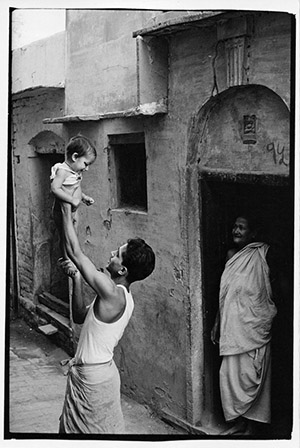

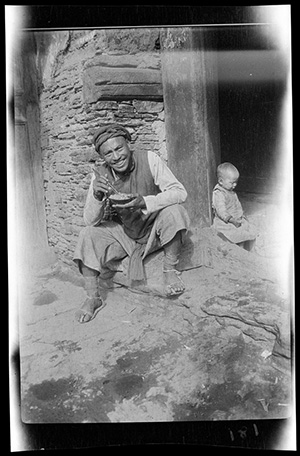

William Gedney Photographs and Writings

Parts of this collection are published, but we are expanding and improving the online collection dramatically.

What the public sees: poignant and powerful images of everyday life in an array of settings (Brooklyn, India, San Francisco, Rural Kentucky, and others).

What I see: 50,000 items in lots of formats; this project could take over DPC photographic digitization resources, all publication resources, all my meetings, all my emails, and all my thoughts (I may be over dramatizing here just a smidge). When it all comes together, it will be amazing.

Benjamin Rush Papers

We have just begun working with this collection, but the Devil’s Tale blog recently shared a sneak preview.

What people will see: letters to and from fellow founding fathers including Thomas Jefferson (Benjamin Rush signed the Declaration of Independence), as well as important historical medical accounts of a Yellow Fever outbreak in 1793.

What I see: Ben or when I’m really feeling it, Benny. We are going to test out an amazing new workflow between ArchivesSpace and DPC digitization guides with Ben.

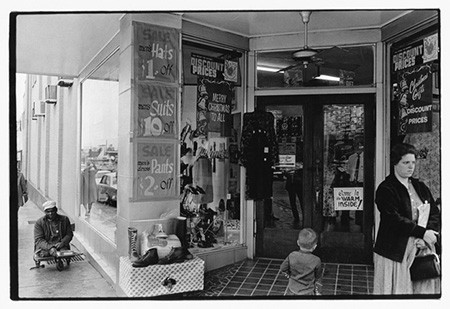

This collection of photographs was published in 2008. Since then we have added more images to it, and enhanced portions of the collection’s metadata.

What others see: a striking portfolio of a Southern itinerant photographer’s portraits featuring a diverse range of people. Mangum also had a studio in Durham at the beginning of his career.

What I see: HMP. HMP is the identifier for the collection included in every URL, which I always have to remind myself when I’m checking stats or typing in the URL (at first I think it should be Mangum). HMP is sneaky, because every now and then the popularity of this collection spikes. I really want more people to get to know HMP.

The Orphans

The orphans are not literal children, but they come in all size and shapes, and span multiple collections.

What the public sees: the public doesn’t see these projects.

What I see: orphans – plain and simple. The orphans are projects that started, but then for whatever reason didn’t finish. They have complicated rights, metadata, formats, or other problems that prevent them from making it through our production pipeline. These issues tend to be well beyond my control, and yet I periodically pull out my list of orphans to see if their time has come. I feel an extra special thrill of victory when we are able to complete an orphan project; the Greek Manuscripts are a good example. I have my sights set on a few others currently, but do not want to divulge details here for fear of jinxing the situation.

I could go on and on about how the logistics of each project shapes and re-shapes my perspective of it. My point is that it is easy to temporarily lose sight of the digital collections garden given how entrenched (and even lost at times) we are in the weeds. For my part, when I feel like the logistics of my projects are overwhelming, I go back to my favorites folder and remind myself of the beauty and impact of the digital artifacts we share with the world. I hope the public enjoys them as much as I do.