I’m not sure anyone who currently works in the library has any idea when the phrase “Section A” was first coined as a call number for small manuscript collections. Before the library’s renovation, before we barcoded all our books and boxes — back when the Rubenstein was still RBMSCL, and our reading room carpet was a very bright blue — there was a range of boxes holding single-folder manuscript collections, arranged alphabetically by collection creator. And this range was called Section A.

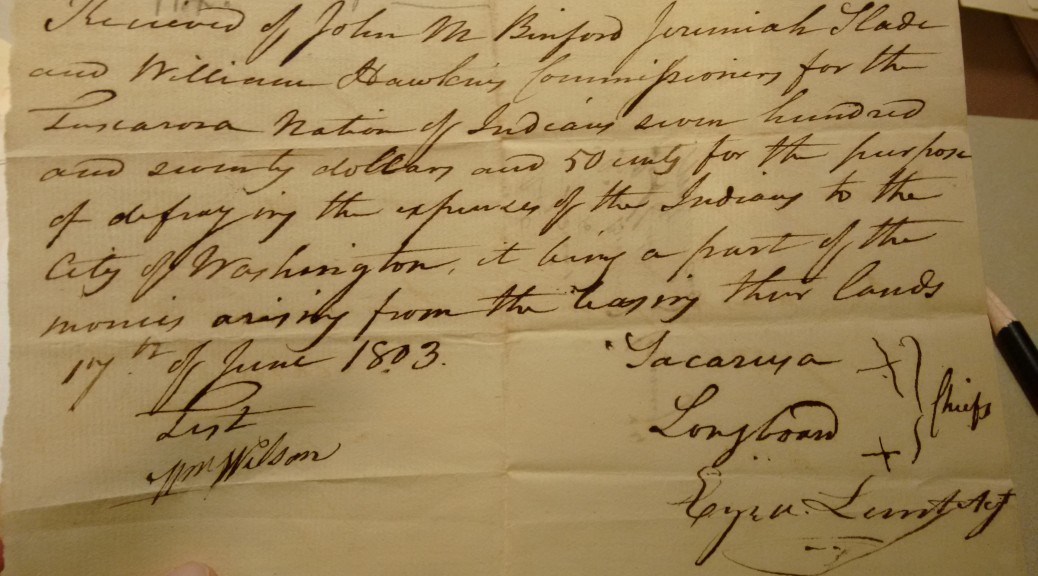

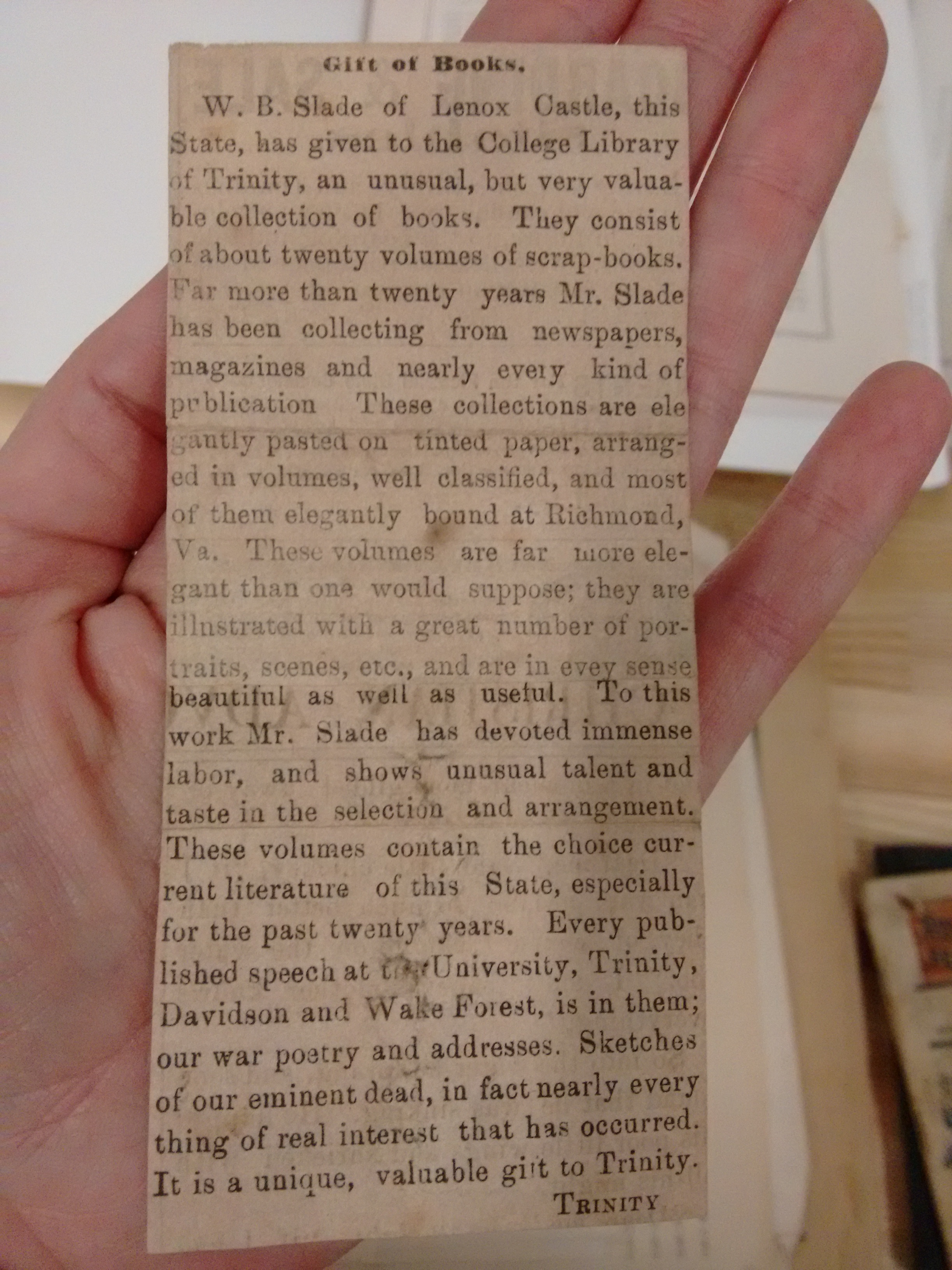

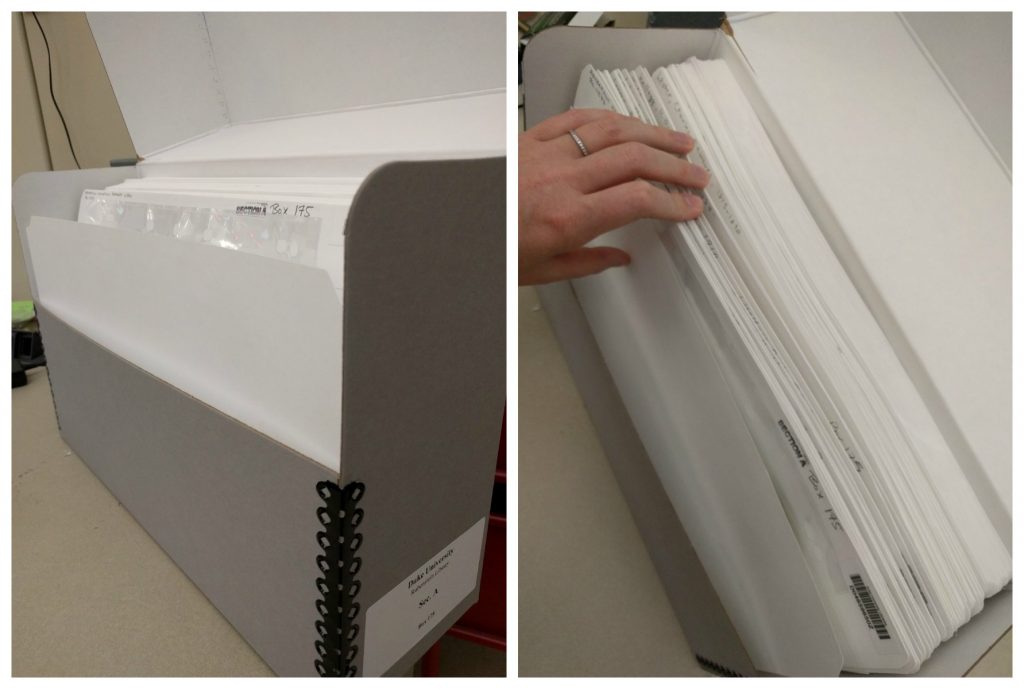

Presumably there used to be a Section B, Section C, and so on — and it could be that the old shelf ranges were tracked this way, I’m not sure — but the only one that has persisted through all our subsequent stacks moves and barcoding projects has been Section A. Today there are about 3900 small collections held in 175 boxes that make up the Section A call number. We continue to add new single-folder collections to this call number, although thanks to the miracle of barcodes in the catalog, we no longer have to shift files to keep things in perfect alphabetical order. The collections themselves have no relationship to one another except that they are all small. Each collection has a distinct provenance, and the range of topics and time periods is enormous — we have everything from the 17th to the 21st century filed in Section A boxes. Small manuscript collections can also contain a variety of formats: correspondence, writings, receipts, diaries or other volumes, accounts, some photographs, drawings, printed ephemera, and so on. The bang-for-your-buck ratio is pretty high in Section A: though small, the collections tend to be well-described, meaning that there are regular reproduction and reference requests. Section A is used so often that in 2016, Rubenstein Research Services staff approached Digital Collections to propose a mass digitization project, re-purposing the existing catalog description into digital collections within our repository. This will allow remote researchers to browse all the collections easily, and also reduce repetitive reproduction requests.

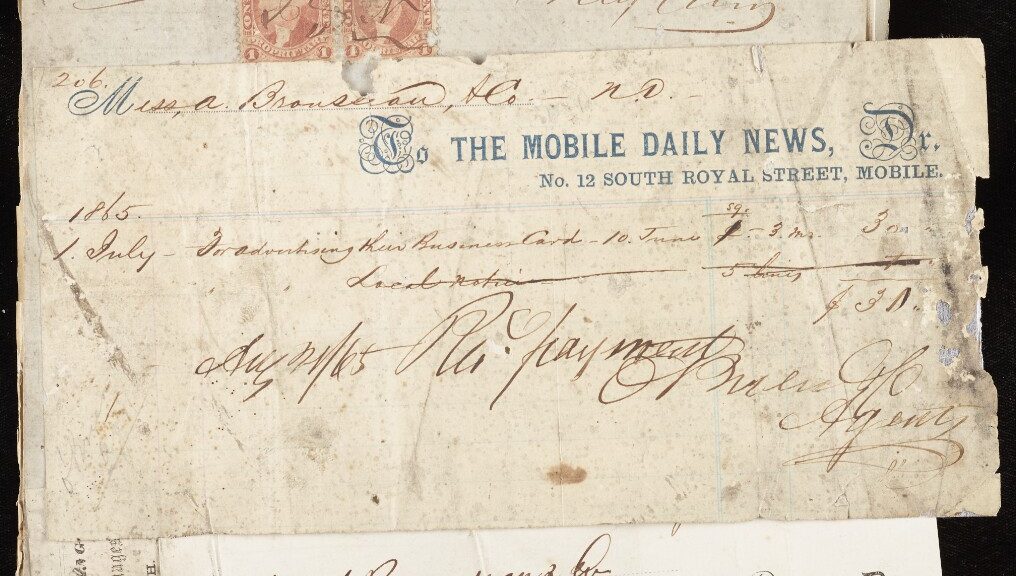

This project has been met with enthusiasm and trepidation from staff since last summer, when we began to develop a cross-departmental plan to appraise, enhance description, and digitize the 3900 small manuscript collections that are housed in Section A. It took us a bit of time, partially due to the migration and other pressing IT priorities, but this month we are celebrating a major milestone: we have finally launched our first 2 Section A collections, meant to serve as a proof of concept, as well as a chance for us to firmly define the project’s goals and scope. Check them out: Abolitionist Speech, approximately 1850, and the A. Brouseau and Co. Records, 1864-1866. (Appropriately, we started by digitizing the collections that began with the letter A.)

Why has it been so complicated? First, the sheer number of collections is daunting; while there are plenty of digital collections with huge item counts already in the repository, they tend to come from a single or a few archival collections. Each newly-digitized Section A collection will be a new collection in the repository, which has significant workflow repercussions for the Digital Collections team. There is no unifying thread for Section A collections, so we are not able to apply metadata in batch like we would normally do for outdoor advertising or women’s diaries. Rubenstein Research Services and Library Conservation Department staff have been going box by box through the collections (there are about 25 collections per box) to identify out-of-scope collections (typically reference material, not primary sources), preservation concerns, and copyright concerns. These are excluded from the digitization process. Technical Services staff are also reviewing and editing the Section A collections’ description. This project has led to our enhancing some of our oldest catalog records — updating titles, adding subject or name access, and upgrading the records to RDA, a relatively new standard. Using scripts and batch processes (details on GitHub), the refreshed MARC records are converted to EAD files for each collection, and the digitized folder is linked through ArchivesSpace, our collection management system. We crosswalk the catalog’s name and subject access data to both the finding aid and the repository’s metadata fields, allowing the collection to be discoverable through the Rubenstein finding aid portal, the Duke Libraries catalog, and the Duke Digital Repository.

It has been really exciting to see the first two collections go live, and there are many more already digitized and just waiting in the wings for us to automate some of our linking and publishing processes. Another future development that we expect will speed up the project is a batch ingest feature for collections entering the repository. With over 3000 collections to ingest, we are eager to streamline our processes and make things as efficient as possible. Stay tuned here for more updates on the Section A project, and keep an eye on Digital Collections if you’d like to explore some of these newly-digitized collections.