How can the Duke Libraries better support the needs of Black students at Duke? A team of library staff conducted qualitative research with Black students over the past two years in order to answer this question. This research was part of a multi-year effort at the Libraries to better understand the experiences and needs of various populations at Duke, beginning with first generation college students and continuing this year with a focus on international students.

Our final report discusses the full research process and our findings in more detail than that provided below, including a full list of recommendations resulting from the study.

We began by reading existing research on university and academic libraries’ support of Black students and speaking with key stakeholders on campus, such as Chandra Guinn, the director of the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture. We researched past studies at Duke that had information on the Black student experience, and learned about the history of faculty diversity initiatives and racist incidents that had taken place on campus. We then held two discussion groups and three PhotoVoice sessions with Black graduate and undergraduate students, in addition to analyzing thousands of responses from the Libraries’ 2020 student satisfaction survey broken out by race. Photovoice is a community-based, participatory research method that originated in global health research. Participants take photos in response to prompts and submit them along with captions. This is followed by a group discussion led by participants as they discuss each set of images and captions.

We sought to understand students’ experiences in the Libraries and on campus to improve how all students interact with library services, facilities, and materials. We did not limit our discussions to library services and spaces, as it was important to explore Black students’ experience and use of the Libraries holistically. The research team pursued eight research questions:

- To what extent are the Libraries viewed as an inclusive space by Black students?

- To what extent is the University viewed as an inclusive space by Black students?

- To what extent do students experience microaggressions or bias because of their race in the Libraries, on campus, in Durham, or in North Carolina?

- What changes can the Libraries make to ensure Black students feel supported and included? How can the Libraries improve spaces, services, and programs to ensure Black students feel supported and included?

- What changes can the University make to ensure Black students feel supported and included? How can the University improve spaces, services, and programs to ensure Black students feel supported and included?

- What campus and community services, spaces, and programs do Black students use and find helpful?

- What library services, spaces, instruction sessions, and programs do Black students use and find helpful?

- What campus and library services, spaces, and programs help Black students feel welcome or supported?

To what extent is Duke University viewed as an inclusive space?

Participants praised many services, programs, and spaces at Duke that contribute to a welcoming environment. At the same time, participants agreed that Duke provides a less inclusive space for Black students than White students. Black students contend with campus culture, curricula, and physical spaces that still largely reflect and center White experiences, history, and values. Academia is a space where Black students do not see themselves valued or accurately represented. From the arts and sciences to statistics and economics, participants reported systemic bias in instructors’ behavior and the scholarship assigned and discussed in class. They experience microaggressions in almost every area of life at Duke. These instances of bias reinforce the idea that their belonging at Duke is qualified.

We found that many Black graduate students have a level of support via their academic programs, beyond what is available to Duke undergraduate students. Participants praised many of their graduate programs for creating inclusive and supportive environments. Elements contributing to such environments include peer and faculty mentors, programs and events, policies, committees, opportunities to be part of decision-making, communication from faculty and administrators, and efforts to increase diversity. Black undergraduate students may be further removed from decision-makers than graduate students, functioning in an anonymous sea of students receiving the same general services. Thus, compared to graduate students, undergraduates may feel less self-efficacy to effect change in campus-wide inclusion efforts.

To what extent are the Libraries viewed as an inclusive space?

Black students largely view the Libraries as inclusive spaces in the sense that they meet their diverse learning needs as underrepresented students at a predominantly White institution (PWI). When asked whether they see the Libraries as inclusive spaces and whether they feel safe, welcome, and supported at the Libraries, both undergraduate and graduate students listed numerous services and resources offered by the Libraries that they value. These include online journals, the variety of study spaces, the textbook lending program, technology support and resources, events and training opportunities, and research support. Respondents reported positive experiences with the Libraries overall.

However, students also reported some negative interactions with staff and with peers in the Libraries. They also perceive aspects of library spaces to be unwelcoming, specifically to Black students because they center White history. Responses to the 2020 student satisfaction survey showed that while around 88% of both Black and White students agreed that the Libraries are a welcoming place for them, only 60% of Black respondents and 66% of White respondents strongly agreed with the statement. Other aspects of the library experience were perceived as unwelcoming for reasons unrelated to race. Though students reported negative experiences in the Libraries, none reported experiencing bias or microaggressions because of their race in DUL.

Students reported a general feeling that both Duke and Duke Libraries, while not actively hostile or racist, are complicit in their silence. Students do not see enough visible actions and signs supporting diversity and inclusion, efforts to limit White western European cultural dominance, or attempts to educate White students about minority experiences. Participants are not convinced that Duke cares about racist incidents, and believe that Duke and Duke Libraries will not take meaningful action if they complain about or report instances of prejudice or microaggression.

What does it mean to be Black at Duke?

“It’s like I have to prove something to somebody: I’m here for the same reason that you are.”

To walk invisible, to speak for all

Students described the contradiction and contrast of seeing oneself almost universally absent – from the scholarship assigned in class and portraits on the walls, to the faces of faculty reflected from the front of class rooms – while simultaneously representing the entire race to others. This is the reality that many experience at Duke, an elite PWI.

Participants discussed being treated as invisible. One undergraduate male shared that even on campus “people usually avoid me with eye contact, crossing to the other side of the street.” It also takes a toll on Black students not to see their backgrounds and experiences represented in the Duke faculty. Currently, Duke’s faculty is significantly less diverse than the study body. Many Black students know the exact number of Black faculty and administrators in their academic programs, and the numbers matter. At the same time, Black students are often unable to fade into a crowd and are forced to be perennially conscious of their race identity in a way that White students at Duke, at PWIs, and in the United States in general, are not. White students and instructors sometimes treat Black students as monoliths, expecting their views and actions to exemplify those of all Black people. Students discussed pressure “to uphold a good image and to go the extra mile…to actively disprove stereotypes.”

One graduate student said:

I feel like I have to speak for everyone…Black people in America don’t have the privilege of individuality.

The validity of Black students’ presence at Duke is challenged both by fellow students and by Durham community members. Black students are hyper-aware that most Black people on campus are staff, not students, and some discussed unease wondering if people mistake them for staff as well. A student explains the need to prove that they belong, not just academically or intellectually, but even physically on campus:

Every time I walk around campus, I’m like, ‘I need to have my book bag on so people know I’m a student, so people don’t think I’m an employee.’… It’s a focus: I have to look like I’m a student. It’s like I have to prove something to somebody: I’m here for the same reason that you are.

A Black undergraduate recounted a story of how she and her friends were aggressively confronted by a group of White male students one night on their way to an event in a campus building who asked, “Do you even go here?” Many participants discussed how demoralizing it is when White people make the frequent assumption that they were admitted to Duke as part of an athletic program, or tell them that they were accepted to Duke as part of a racial quota instead of on the same academic merits as other students.

Graduate students discussed how Duke seems best able to accommodate two specific kinds of Black student, with room for improvement in how it accommodates others:

Duke makes it accommodating for Black students, but only a specific kind of Black student: Black athletes from America, or very rich African kids. I’m African American but not an athlete, or rich. I’m academically curious, and I just feel like I’m alone.

Participants acknowledge and appreciate the diversity of the Black student experience and wish others would do the same. Black students at Duke are rich and poor. They come from countries spanning the globe and from different religions and cultural backgrounds. While some are athletes, most are not.

Being Black at a predominantly White institution

PWIs such as Duke were not originally intended for Black students. Despite the time that has passed and the number of students of color who have been admitted, Duke remains a historically White space, and this history continues to permeate and shape the culture of the campus. The students in our study were fiercely aware of this history.

Undergraduates expressed concerns that many White students have little comprehension of or interest in understanding the experiences of “the Other” and are surrounded by White peers who are often ignorant of and oblivious to American racial dynamics and the realities of racism. Undergraduate participants perceive that Duke’s curriculum does not prioritize ensuring that all students will be exposed to diverse points of view and experiences through required courses or activities, and interdisciplinary courses tend to be racially segregated.

Duke Libraries and Duke as complacent and complicit

There was a general feeling that Duke Libraries and Duke, while not actively hostile or racist, are complicit in their silence. Students do not see enough explicit signals supporting diversity and inclusion, efforts to limit White western European cultural dominance, or to educate elite White students about minority experiences.

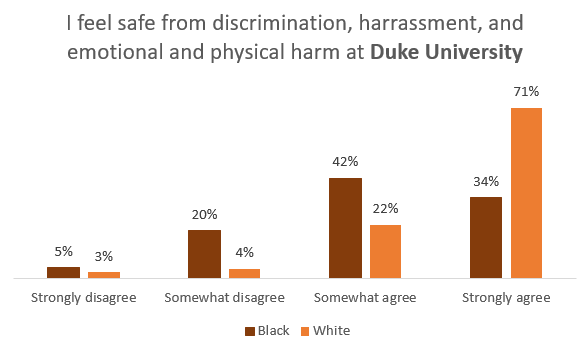

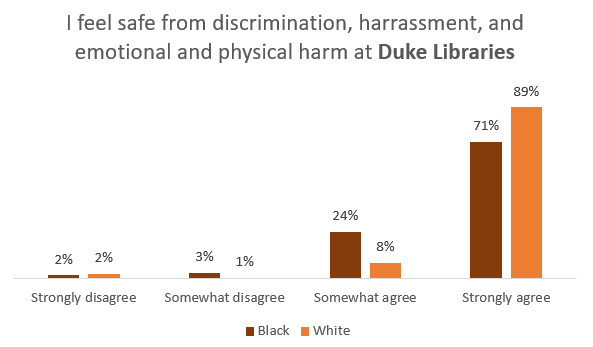

The 2020 Libraries student survey asked students whether they feel safe from discrimination, harassment, and emotional and physical harm at Duke Libraries and at Duke University. There are stark differences by race among the 2,600 students who responded. Black students do not feel as safe from discrimination, harassment, and emotional and physical harm as White students either on campus or in the Libraries.

Fewer (34%) of Black students “strongly agree” that they feel safe at Duke University, versus 71% of White students. A quarter of all Black students do not feel safe to some extent, versus only 7% of White students. More Black and White students feel safe in the Libraries than on campus in general, but fewer Black students “strongly agree” with the statement than White students – 71% versus 89%.

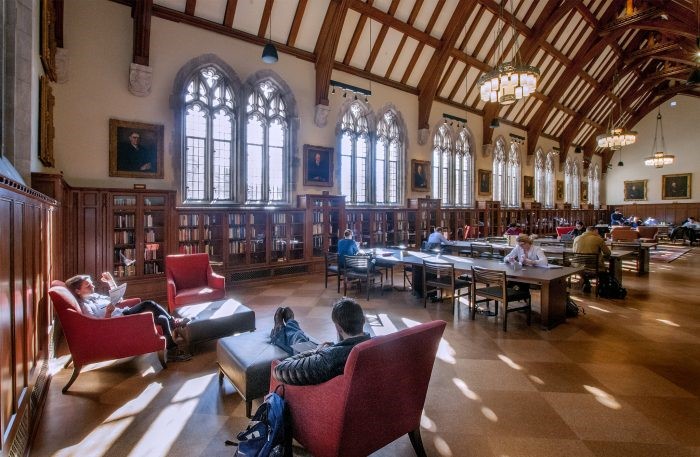

Discussion group participants believe that if campus spaces want to make minorities feel welcome, they need more visible signs or statements about inclusion and diversity, particularly because the default in Duke spaces is overwhelming visible representations of White people and Western art and architecture. In reference to the Perkins & Bostock Libraries, one graduate student said:

I don’t see an active attempt to make it welcoming per se. Depending on…what your experience has been like as a Black student on campus, I think there would need to be a purposeful and very explicit attempt to make it welcoming. Not to say there’s a malicious attempt to make it unwelcoming.

Systemic injustice perpetuated through the curriculum

“We were absent in the scholarship. Not just black people – any people of color. And when it was there, it was highly problematized…Every time people of color are mentioned, it’s in some kind of negative context. We’re deficient in some sort of way.”

Academics at Duke are often a space where Black students do not see themselves highly represented or valued. From the arts and sciences to statistics and economics, participants report systemic bias in a variety of areas ranging from instructors’ behavior to the scholarship assigned in class. A student in a business class reported the glaring lack of a single case study involving a Black-owned business or a business run by Black people. Another graduate student in the sciences explained:

All of the people you study are dead White men. And if you never did any outside scholarship yourself, you might be convinced that those are the only people who have ever done [redacted] science in the world.

In addition to racial biases in scholarship assigned, participants discussed the behavior of faculty and instructors as it contributed to systemic injustice in the classroom:

Particularly in statistics classes, almost all data that were racialized normalized Whites and problematized Blacks and other minorities, relatively. There was one assignment where we were supposed to look at and interpret the data, and White people were clearly worse off. The professor did gymnastics to interpret it in such a way where Black people would still be worse off. Come on! They couldn’t even see a way for White people to ever be worse off. And this happens all the time. Whether it’s a guest lecture or whatever…They just focus on the disparities, they interpret it very narrowly, and then there’s no discussion of the origins of those disparities or any solutions to them.

Black students often expect to face racial bias in their daily lives outside academia or from other students on campus. But faculty are both mentors and authority figures who represent the face of Duke to their students. Their silence can speak as loudly as their words in molding students’ perceptions of the extent to which Duke, as well as academic fields more broadly, value them.

On White and Western dominance of physical spaces

Physical spaces communicate priorities, expectations, and cultural values both implicitly and explicitly. They do this via architecture, materials in the spaces such as art, signs, and decorations, and social groupings within spaces. There are parts of Duke that Black students find welcoming and inclusive, but overall, participants do not consider the physical spaces of campus to be as inclusive for Black students as they are for White students.

Students across discussion groups listed example after example of spaces at Duke – including a number of libraries – where art and architecture caused physical spaces to feel exclusionary. Duke’s campus and libraries are filled with photography, statues, and portraits depicting mostly White males. This theme was raised by both undergraduates and graduates as a way that campus spaces make Black students (and likely other groups) feel unwelcome and excluded:

In the library at the [professional] school, there’s this room…A bunch of huge paintings of old White guys…It means something, right? Because there’s no other part of that library where you’ll see a big portrait painting of someone who isn’t a White male. It’s more White supremacy in itself: the absence of other people being represented in this school says a lot. If they wanted to do something about it they could. They could put in more paintings. There have been people of color who’ve been through Duke and have gone on to do great things.

A number of the discussion groups touched on a related topic, which is the lack of a library or a room within the main campus library dedicated to Black studies. Many students came from undergraduate schools that did have such spaces and were surprised to find them lacking at Duke, especially given the presence of the Nicholas Family Reading Room for International Studies (referred to by students as the “Asian reading room”), which houses reference collections for many non-English languages – though not all Asian. One of the more common recommendations across discussion groups was to create such a space within Perkins & Bostock Libraries, similar to the Nicholas Family Reading Room. Such a space would display books and journals related to Black studies or Black history and feature art, photographs, or exhibits related to Black culture or the history of Black people at Duke or in Durham.

Study spaces as social territories

Another aspect of Perkins & Bostock Libraries that feels exclusionary to participants is the territorial dominance of in different parts of the Libraries. This issue was also raised by students in numerous free-text comments of the 2020 student satisfaction survey, focused on Greek Life members laying an unofficial claim to library study spaces. Participants explained that these groups’ behavior often causes students unaffiliated with those fraternities to feel unwelcome in these public, highly-valued study spaces. Both discussion group participants and survey respondents also complained about the groups disturbing other students by not following posted noise norms for quiet study zones and even using library study rooms for fraternity business. One survey respondent said:

The library is divided (perhaps unofficially) into study areas based on Greek and SLG membership. I consider this to be a disgusting practice and it also leaves me (a graduate student) unsure where I can comfortably sit. I just wish the library was not yet another place where the caste system that is the Duke social scene gets reinforced.

Several students discussed how fraternities sometimes reserve bookable library study rooms and use these spaces for business purposes, to bestow access to social resources (in this case, access to parties) that are highly exclusive and closed to the majority of the campus, which further perpetuates exclusivity on campus. The language the students use to describe these interactions (“ostracized,” “uncomfortable,” “not welcomed”) shows the extent to which the presence of these groups in library spaces that are supposed to be inclusive actually makes students feel excluded, as if they cannot use those spaces due to their lack of membership in those groups.

Features of a space matter

The Libraries’ 2020 student survey asked whether respondents enjoy working in a campus library more than other campus spaces. A third of White students “strongly agree” with this statement, versus one-fourth of Black students. Participants in our discussion groups highlighted three features that greatly contribute to study spaces feeling welcoming and supportive, which are likely true for students from all backgrounds: natural light, green spaces and greenery, and vibrant colors.

Library staff have long been aware that students can study and de-stress better in library spaces with natural light. Increasing natural light is only possible when planning and constructing new facilities, but we can review the current spaces to ensure that all areas with natural light have seating options around them. Participants discussed how greenery, even fake plants, contribute to mental well-being and create study spaces that are less stressful. This also includes views of nature out of windows. Vibrant colors and artwork were mentioned time and again as factors that create positive energy and support well-being. Both the Link on the first floor of Bostock Library and the Bryan Center were held up as examples of well-designed spaces at Duke with brightly colored walls and furniture, or artwork.

In comparison, the Perkins & Bostock Libraries were seen as having much room to improve, with the exception of the following spaces: the Link, The Edge, the large reading rooms, light-filled breezeways, and the newly renovated Rubenstein Library. Participants requested that the Perkins & Bostock Libraries modernize its decor and add vibrant colors via paint, carpets, furniture and art. The students feel that the drab colors in study rooms and general open study areas exacerbate the sense of stress that already pervades the library. Students had unapologetically negative views of the atmosphere produced by color and decor choices:

I think Perkins is so uninviting…At a basic level, it’s just not a comfortable, inviting space to me. I hate the lighting. Part of it is that there is very little natural light throughout the library but then I just don’t like the colors that are chosen… It’s depressing. It just seems very outdated.

Campus and library wayfinding came up in multiple discussion groups as an area that needs improvement and contributes to students feeling unwelcome and stressed. Duke’s policy to not have visible external building signage and to use the same architecture for most buildings on West Campus leads newcomers to feel excluded and lost. Participants were critical of the fact that the main campus library has no identifying external feature or sign. Participants also discussed the need for better internal directional and informational signage within the Libraries. Improved signage is necessary both to assist with finding materials, and for guidance on use of study rooms and computer look-up stations. Students like the noise norms and zones designated by signage within the Libraries and want this signage to be larger and more prominent.

Affinity spaces are critical and signal what Duke values

Spaces noted by participants as welcoming and supportive included the Mary Lou Williams Center for Black Culture, the Wellness Center, the West Campus Oasis, the Duke Chapel, the Women’s Center, the Bryan Center, gardens and green spaces, and the Center for Multicultural Affairs. Students also spoke enthusiastically about a number of campus services, including the on-campus dentist; Wellness Center activities like a weekly group therapy session for Black women and free physical assessments; movie nights at the Bryan Center; campus buses; the entrepreneurship program; CAPS; the Writing Studio; and state-of-the-art gym facilities.

Many Photovoice participants submitted photographs and captions about the Mary Lou Williams Center, its programming, and its staff. For participants, the fact that Duke University funds and supports programming for such a large, beautiful space highlights Duke’s commitment to Black students and Black culture. However, not everyone feels welcome on the campus as a whole. One student said they go to the Mary Lou to “escape the white gaze” of the broader campus. These spaces should not be seen as spaces one has to go to escape the general campus experience, but rather as spaces that contribute to their campus experience.

Graduate students talked about the robust support networks in their academic programs. Students reported feeling supported in many ways, from professors who learn students’ names and Deans attending welcome lunches with new students, to orientation activities, peer and professor mentor programs, support for healthy work-life balances, and committees on diversity and inclusion.

Participants felt welcomed by events hosted solely for Black students, such as Black Convocation and parties held by Black Greek organizations, as well as outreach from the Mary Lou Williams Center to all incoming Black students.

Library services support students

Library services that were praised included library materials and online resources; the library website; textbook lending; device lending; technology such as scanners, 3D printers, and DVD players in Lilly; events such as snacks and coffee in the library and Puppies in Perkins during finals week; orientation sessions; reservable study rooms; designated noise norms and zones; ePrint; personal assistance from librarians; and Oasis Perkins.[1] Students are surprised by how many services the Libraries offer and want more marketing and information about these services. Library staff should continue to develop outreach strategies for marketing services to students at various points in their programs and majors, both online and within library spaces.

The Libraries textbook lending program came up in every undergraduate discussion group. Students were enthusiastic about the program and the financial burden that it alleviates.

I think [library] rental textbooks are really nice…Knowing that if I change a class I don’t need to buy this book the first week and resell it for only 30%. If you’re paying for your own books, that’s not feasible. It’s…another stress coming into your freshman year of college. Thinking, ‘oh no I have to buy this $200 math book online – no, you can rent it from the library until you know whether you’re even supposed to be in that math class.’ Knowing that I can get through the first part of the semester without having to worry about textbooks is big.

According to results from the Libraries’ 2020 student survey, about one-fourth of all undergraduate students (regardless of race) said that textbook lending is important to them. At the same time, only 48.5% of both Black and White students said that the current program completely meets their needs, and 8% of those who said textbook lending is important to them reported being unaware of the Libraries textbook lending program. The survey also provided the following open-ended prompt to students: “In a perfect world, with unlimited time and resources, the Libraries would…” Eight percent of responses (127 out of 1,535) included a request for the Libraries to provide free textbooks.

Person-to-person interactions make a difference

Interactions with other people can be critical contributors to whether students at Duke feel welcome and supported. Participants discussed many positive interactions on campus and in the Libraries, with library service desk staff, librarians assisting with research, friendly security guards, housekeeping staff, academic program office staff, Mary Lou Williams Center staff, and financial aid officers. Black staff at Duke also provide important social support for students, whether assigned as mentors or simply lending a sympathetic ear. One student immediately thought of a staff member when asked about the most helpful programs and services on campus:

It’s not a program, it’s [an office administrator]. Since she’s a sister, we can just talk about anything. She looks out for me in a way that I know only a Black person would look out.

Library security guards stand out as a group that can help students feel safe and supported with just a friendly word or wave (though as previously noted, security guards can also easily make Black students feel unwelcome):

First semester sophomore year when I was [at the library] really late, there was this one security guard who I saw just going around and around, and each time he would wave. Then I was studying there just two nights ago, I just saw him again and he waved, and it just felt really good.

Affinity groups are important to all students, and especially important to minorities at PWIs. Students mentioned feeling welcomed by the existence of campus student groups such as the Black Student Alliance and Black Graduate & Professional Student Association, Black Greek Life, and spaces for affinity groups to gather (such as the Mary Lou and Black Student Alliance office).

Participants discussed many positive interactions with library staff. Participants value friendliness and good customer service, as well as subject expertise. However, discussions highlighted the fact that initial impressions and experiences are critical, and if students’ initial interaction is negative, they are likely not to come back. In particular, library staff must be mindful of the delicate balance between their roles as teachers and as service providers. While many library staff are trained to teach research skills, students often approach the service desk expecting staff to help them complete their task as quickly and efficiently as possible. Efforts to teach them how to complete the action by themselves instead of just assisting them can be interpreted as patronizing, a rebuke for having “bothered” staff, or poor customer service.

Overall, participants have a positive view of the Libraries. They recommended improvements, especially for physical spaces, and underscored the importance of marketing services such as textbook lending and relaxation events. Participants shared valuable insights that can help library staff understand what it means to be Black at Duke and in Durham, and ways that library staff can make spaces more welcoming and help ease the burden that Black students feel on a daily basis.

What’s next?

These findings became the basis of 34 recommendations outlined in the research team’s full report. One of the top recommendations from participants is that the Libraries dedicate a study space to Black scholarship. Such a space was envisioned to include art, photographs, or exhibits related to Black culture and history and highlight library resources from Black scholars.

The research team has presented and discussed this study at all staff meetings at the Libraries, as well as to various groups and units on Duke’s campus over the summer of 2020. The report was shared widely within the library community to encourage other libraries to consider these questions and undertake similar work.

In August 2020, the Libraries formed a Black Student Study Next Steps Coordinating Team charged with prioritizing and coordinating the implementation of recommendations from the study, as well as additional recommendations that came out of a staff workshop delving into the Libraries’ 2020 student satisfaction survey. For more information on this study or the Coordinating Team, contact Joyce Chapman joyce.chapman@duke.edu.

I am VERY sorry that the library feels it necessary to take on this ridiculous issue . A library is just a library. It is as “inclusive” as any other space — not that “inclusivity” should even be a library issue. So, please, get off this train and just worry about books!

Beyond storing books, libraries provide opportunities to explore research, experience new ideas, gather with others, find peaceful spaces, gain skills, and access knowledge. They are meant to serve these functions for everyone in our community. In order to do this, they need to put in the work to overcome systemic racist structuring. If you need resources on the systemic racist structuring of our society, our excellent libraries are a great place to start.

I am really glad DUL has taken on this hot topic. For years, ethnic students and those have not been always treated with equality and respect across campus. While some may not have seen or felt the injustices but that does not mean it isn’t happening. I think it is important that the library is open and inclusive to ALL patrons, and each is treated with respect. Duke is a community of many colors, nationalities, sexual identities and religions. All should be respected.