As a Humanities Writ Large Fellow at Duke this year, one of my goals was to explore the archives in the Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Collection, extending work I had done at the Kislak Center for Special Collections at University of Pennsylvania creating archival research exercises for undergraduate humanities students. My scholarship focuses on late nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century American women’s writing, so I knew that exploring the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection, currently undergoing processing, would be especially exciting. But little did I know that I would uncover a genuine “find”—an Italian-language typescript of a short story by Edith Wharton, translated by the author and featuring corrections in her own hand.

The typescript, the only piece in the collection by Wharton, is a translation from English into Italian of Wharton’s story “The Duchess at Prayer” (“La Duchessa in Preghiera”). The textual history of this story is complicated: Wharton first published the story in Scribner’s in August 1900, where it featured illustrations by Maxfield Parrish (full text at hathitrust.org) and then republished it in the short story volume, Crucial Instances (1901). The translation in the Rubenstein appears to have been made after the 1900 publication. Drawing on Honoré de Balzac’s “La Grande Bretèche” (1831) and likely Robert Browning’s “My Last Duchess” (1842), Wharton’s tale recounts the story of a seventeenth-century Italian Duchess whose cruel husband discovers her adulterous affair. To taunt and threaten his wife, the Duke gives her a Bernini statue crafted in her image, and, as Emily Orlando has argued in Edith Wharton and the Visual Arts, in the conclusion of the tale, the woman “becomes a statue chiseled in marble at her husband’s command” (45). The typescript in the Rubenstein appears to be a word-for-word Italian translation of the Scribner’s version, though that will have to be confirmed against the version of the short story in Crucial Instances.

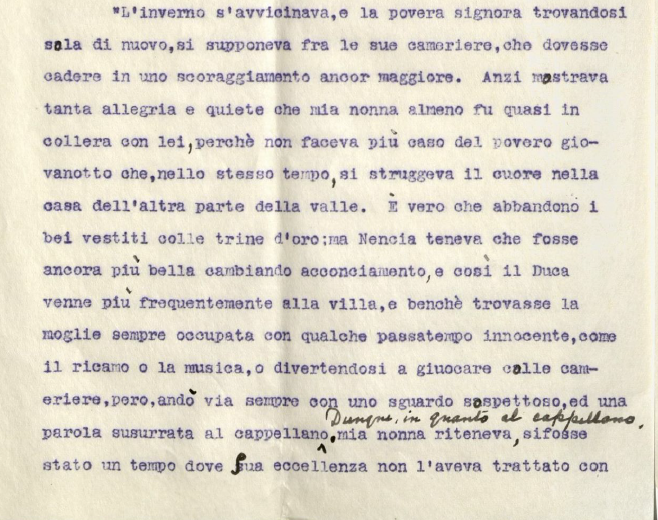

“La Duchessa in Preghiera” attests to Wharton’s linguistic expertise. The author, who spent much of her childhood in Italy and adulthood in France, was fluent in multiple languages. There’s no evidence that the story was published in Italian periodicals of the day; rather, it seems most likely that Wharton translated the story as a language exercise. In this translation, Wharton’s sophisticated Italian reveals her careful self-education; for example, she uses the passato remoto to refer to events in the distant historical past, where a less experienced Italian writer might use the passato prossimo. On the typescript pages, we see how Wharton added accent marks that were not available on English-language typewriters at the time (figure 1; no Microsoft Word symbols here!). Wharton used her own work as a source of language practice several times during her career: she first conceived the novella Ethan Frome as a French exercise and translated some of her stories from English to French for publication in French periodicals. The typescript in the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection reveals her immersion in Italian culture as well her mastery of two languages. Just a year after the publication of Crucial Instances, she would publish her first novel, The Valley of Decision (1902), set in eighteenth-century Italy.

While “La Duchessa in Preghiera” deepens our appreciation of Wharton’s multilingualism, it also advances the scholarly record in another way. I am one of a number of volume editors contributing to The Complete Works of Edith Wharton, to be published by Oxford University Press. To date, there is no authoritative scholarly edition of Wharton’s complete works. In the process of editing Wharton’s extensive corpus, volume editors must locate extant manuscripts and typescripts for all the works in their purview. “La Duchessa in Preghiera” suggests that Whartonites should expect to find her work in unexpected places.

For example, after finding the typescript in the Rubenstein, I learned that an additional copy of “La Duchessa in Preghiera” has been located in the Matilda Gay papers at the Frick Museum in New York. Matilda Gay was a friend and neighbor of Wharton’s in Paris and two women came from a similar social class in New York. The next step would be to compare the Rubenstein typescript with the version in the Frick. The existence of these translations elicits multiple questions: did Wharton share a translation with her friend, and for what purpose? Do the two versions differ in any way? What do these translations tell us not simply about the author, but about the sharing of texts between friends, two female expatriates, at a particular historical moment, grappling with life and literature in another language? As with many forays into the archives, this initial exploration of the Lisa Unger Baskin Collection reminds us of how much we still have to learn.

Post Contributed by Meredith Goldsmith, Humanities Writ Large Fellow 2015-2016 (Associate Professor of English, Ursinus College)