Post contributed by Joshua Larkin Rowley, Reference Archivist, John W. Hartman Center for Sales, Advertising & Marketing History.

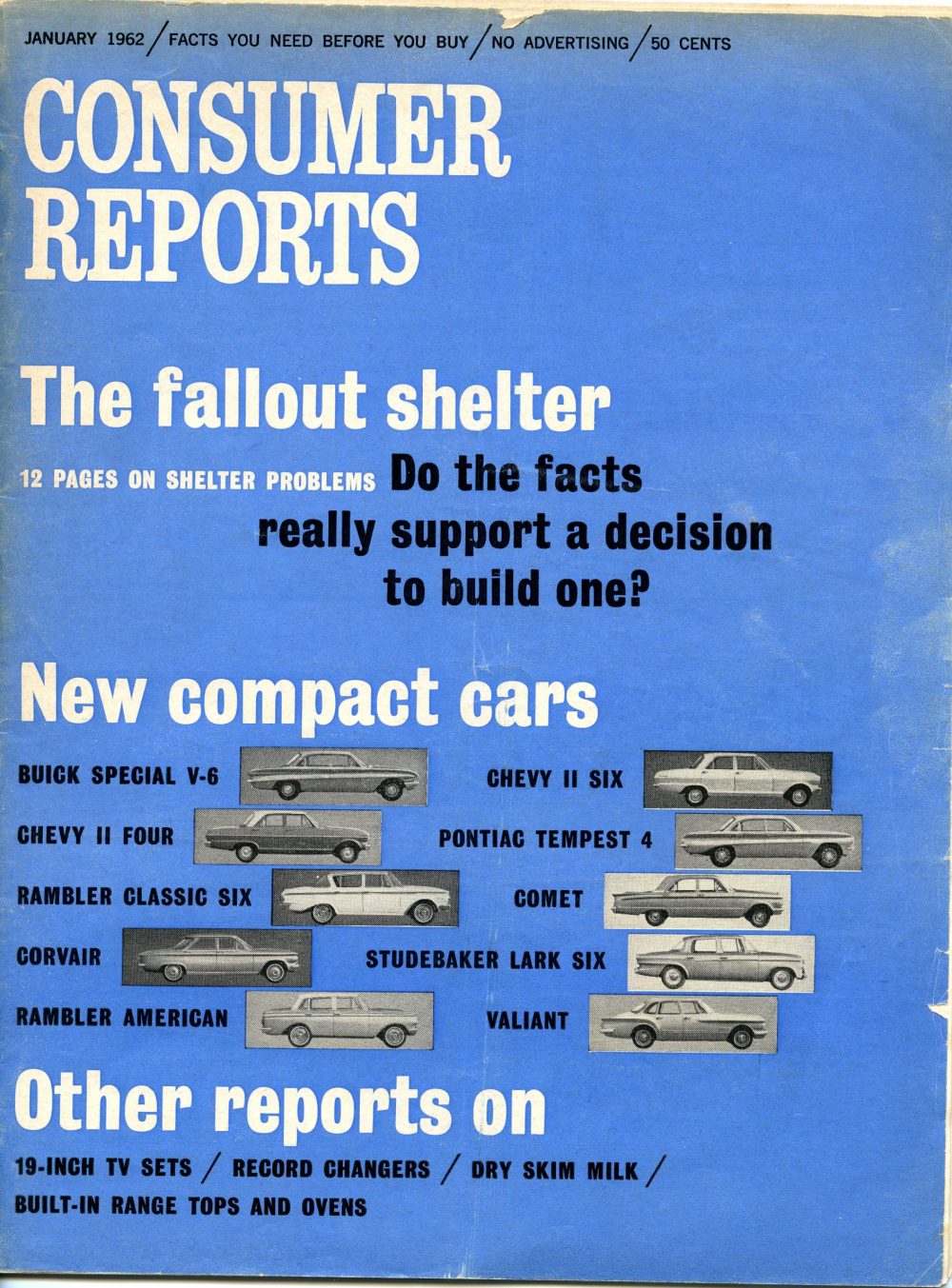

The January 1962 issue of Consumer Reports, the flagship publication of the consumer education and advocacy non-profit of the same name, included a much-anticipated article titled “The Fallout Shelter: A review of the facts of nuclear life and the variables that bear on the effectiveness of a shelter.” Cold War consumers were eager for guidance from a trusted source of product evaluation. However, Consumer Reports essentially took a pass. According to the organization, all the variables that might make a shelter effective or ineffective were simply unknowable and unpredictable. While the organization side-stepped recommending specific shelters, the Technical Department, the unit responsible for creating testing procedures, methods, and reports, retained forwarded letters documenting reader reactions to the article. For a moment, the fallout shelter article became a flashpoint for the hopes, fears, and anxieties of Cold War citizens.

Some readers applauded the article as the most objective and thorough review of the facts regarding the effectiveness of fallout shelters. Others were not so complimentary. A professor of architecture at the University of Florida and self-described instructor in “Fallout Shelter Analysis,” accused the organization of using the same tactics as cigarette advertisers, “arguing from a conclusion using pseudo-technical jargon.”[1] Another agreed that Consumer Reports had not “..lived up to its own standards in discharging the awesome responsibility…of giving advice that might mean life or death to large numbers of people.”[2] Some took an optimistic something-is-better-than-nothing stance. “You apparently cannot admit that a partial solution is better than no solution at all,” wrote one subscriber.[3] Yet another reader relays that he is often asked by friends and acquaintances whether he is afraid that the shelter he is currently constructing might not work. His reply, he shares, is always: “No—My greatest fear has been that it (nuclear war) might happen, and I would be faced with the knowledge that I hadn’t even tried or made the effort.”[4]

Other readers felt the article reinforced their own principled stance concerning nuclear armament. A letter from a couple from Bellaire, Ohio included their own vision of Civil Defense titled Civilization Defense: A Creed, in which they lay out a list of principled teachings that they plan to instill in their children amid the omnipresent threat of nuclear war which concludes: “This creed is the only shelter I will build for my children.”[5] A research psychologist at the University of Michigan argued that the greatest threat posed by the fallout shelter fad was not their inadequacy, but their “psychological and political consequences during a time when an attack might still be prevented.” He goes on to argue that shelter programs are but “a step in the long chain of events” that could actually provoke a nuclear war. Lynn and Michael Phillips of Berkley, CA, agreed, commending the article’s importance in “preventing people from making the deadly mistake of accepting nuclear war” as a means to rid the world of Communism and survive. In the mind of the Phillips’s the only way to protect a nation’s people from nuclear war was disarmament.

Consumer Reports was also critical of companies eager to leverage the demand for fallout shelters. In an article titled “Enter the Survival Merchants,” the magazine characterized the “survival business” as a natural home for “fly-by-night operators, high pressure salesman, and home improvement racketeers” and accused the industry of preying on people’s fear as well as their patriotism. A letter from an executive at KGS Associates, later to be revealed as a civil defense merchandiser, accused the publication of intentionally setting out to discredit the civil defense industry. In the case of a nuclear attack, the writer wondered “how fast the Consumer Reports staff…will run for the shelters, eat the food, and drink the water provided by the men they have described as hungry, callous, and even a bit shady.” Another shelter defender pointedly stated, “your implication that all shelter designers are out to fleece the public is untrue and not up to the high standards I have always looked for in Consumer Reports.”[6] The organization did not let large corporations off the hook either. General Mills, the processed foods manufacturer, also came under fire for their marketing of Multi-Purpose Food (MPF), a shelf-stable nutritional supplement designed specifically to stock fallout shelters and meant to be mixed with other foods. Brochures for the product were often displayed alongside fallout shelters at civil defense trade shows, piggybacking on the shelter craze.

Looking back on the controversial issue two years removed from its publication, Consumer Reports staff took time for an LOL moment. In an internal memo, a staff member noted an article published in the New York Post that day about fallout shelters that cited a local company “…buying up prefabricated fallout shelters for conversion to hot dog stands and cabanas. ‘Swords into plowshares’” he quipped.[7]

[1] King Royer to Consumers Union, 12 January 1962. Consumer Reports. Technical Department Records, Box 54

[2] Jack Hirshleifer to Irving Michelson, Director of Public Service Projects, 15 March 1962, Ibid.

[3] John F. Devaney to Dexter Masters, Director, Consumers Union, 11 January 1962 Ibid.

[4] Thomas McHugh to Consumer Reports, 8 April 1962. Consumer Reports. Technical Department Records, Box 54.

[5] Charlotte Levine to Consumer Reports, 14 January 1962, Consumer Reports. Technical Department Records, Box 54.

[6] McHugh to Consumer Reports.

[7] Memoranda, 17 July 1963, Consumer Reports. Technical Department, Box 54