Post contributed by Amelia Wimbish, DCL at Duke Intern

Today we celebrate the birthday of Lyda Moore Merrick: an artist, a teacher, and a steward of community life in Durham. She was attentive and deliberate in how she showed up for others, offering her abilities where they were needed. People who knew her remembered her patience, her composure, and the thoughtful way she moved through the world.

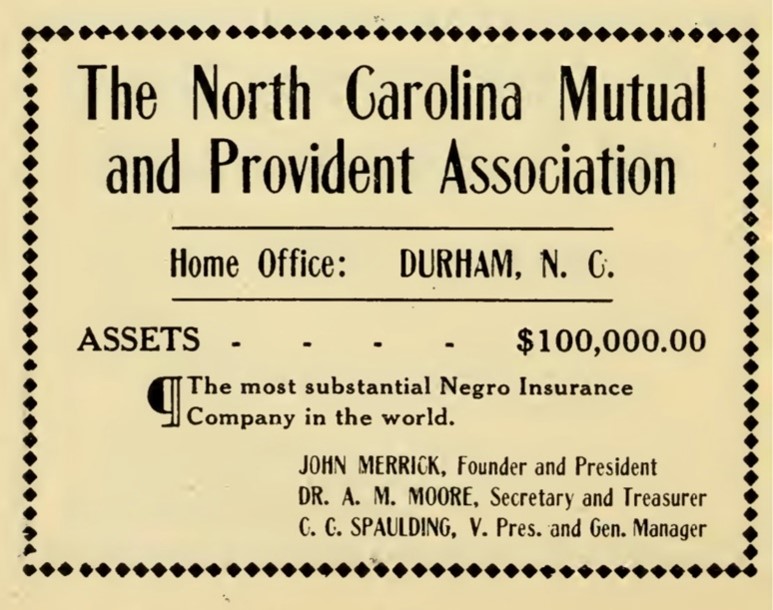

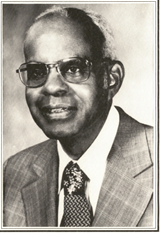

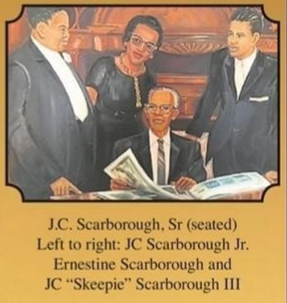

She was born on November 18, 1886, in a home on Fayetteville Street where her parents, Sarah McCotta “Cottie” Dancy Moore and Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore, cared for neighbors before a hospital for Black residents existed in Durham. The rhythm of that household formed her understanding of responsibility and how one might carry it. Her life is documented not only in her father’s papers but also in the papers of Dr. Charles DeWitt Watts, her son-in-law, whose correspondence and family materials help preserve her story.

Lyda was observant and patient, drawn to books, art, and music. At Whitted School she excelled in her studies and graduated as valedictorian. She continued her education at Barber-Scotia Seminary in Concord, a school that prepared Black women to teach and to serve their communities, and then at Fisk University, where she earned her degree in music with honors in 1911. Later she studied art at Columbia University. These institutions connected her to networks of Black educators, artists, and cultural workers and affirmed what she had already learned at home: knowledge holds value when it is shared. She often remembered watching her father read his Bible and study medical research late into the night, long after his formal training had ended. From him she learned that responsibility was not a task completed, but a way of living.

In 1916 she married Edward Richard Merrick. Their home at 906 Fayetteville Street became a place for lessons, conversation, and encouragement. She taught piano and violin to students of many ages, guiding them toward confidence through daily practice. She served as organist at St. Joseph’s AME Church, where music shaped both worship and community life. Those who studied with her remembered calm instruction paired with high expectations, and an approach to teaching that treated skill as something developed over time.

Lyda made art throughout her life. She painted portraits and landscapes and often worked from memory to hold on to places and people who mattered. Her portrait of her father, completed in 1940, remains on display at the Stanford L. Warren Branch of the Durham County Library. Later in life, she drew a detailed map of Hayti from her recollection, recording the neighborhood’s homes, streets, and gathering places. Her art was a form of remembrance, a way of keeping community life visible and known. Across her life, she treated art, teaching, and community work as one practice: preserving what mattered by making it shareable.

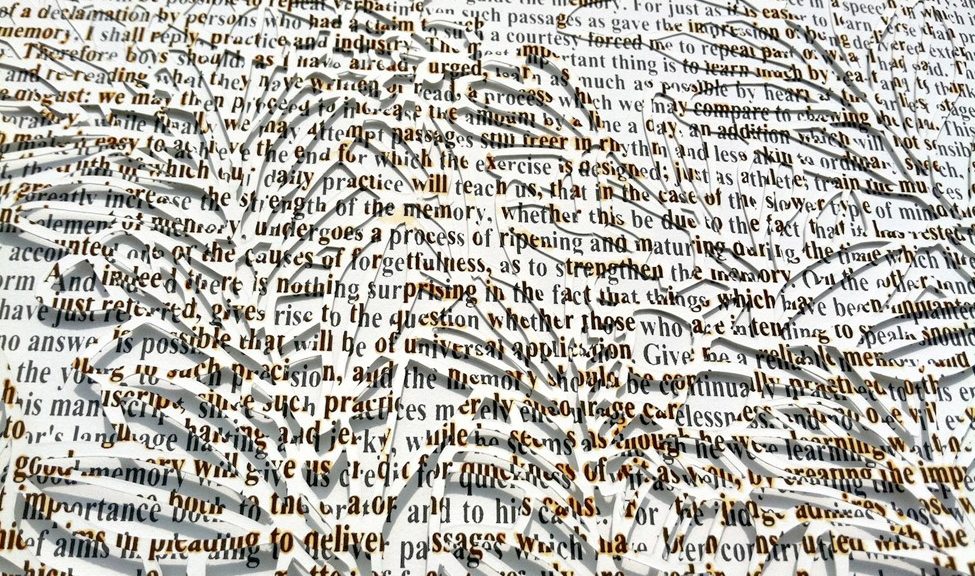

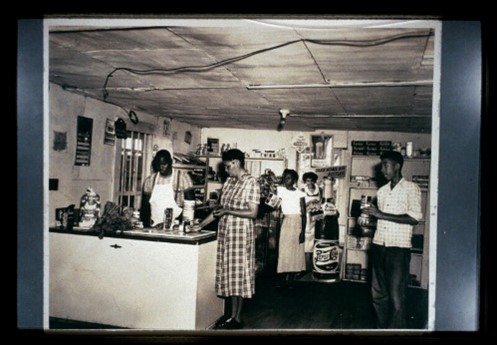

Her work with blind readers grew from a long relationship. As a young mother, she came to know John Carter Washington, who was blind and deaf from infancy and was receiving care through Lincoln Hospital, where her father worked as a physician and as hospital superintendent. Their friendship endured for more than sixty years. When Washington noted the lack of reading material available to Black blind readers, Lyda responded. In 1952 she founded The Negro Braille Magazine, later adopted as a project of the Durham Colored Library. Volunteers gathered regularly to transcribe essays, sermons, and articles into Braille by hand. The magazine reached readers throughout the United States and internationally. Later renamed The Merrick Washington Magazine, it continued for decades under her daughter’s and later her granddaughter’s leadership. It remains a rare example of Black-led accessible publishing and a testament to collective effort. In 1973, her leadership in the project was recognized by a letter of commendation from the White House.

Recognition of Lyda’s work came steadily across her life. Community organizations, cultural groups, and professional associations honored her not just for what she accomplished, but for how she carried her responsibilities. Delta Sigma Theta Sorority and Links, Inc. of Durham recognized her leadership. The Daughters of Dorcas and Sons Quilting Guild honored her role in sustaining craft and cultural memory. The North Carolina Library Association granted her honorary membership for her leadership with the Durham Colored Library, her way of continuing her father’s legacy. The Hayti Heritage Center named a gallery in her honor, a testament to her influence on Durham’s artistic life.

Late in life, Lyda reflected on her experiences in an oral history published in Hope and Dignity: Older Black Women of the South. She spoke about the institutions her community built and maintained, and about the belief that cultural and educational life should be shaped by those who participate in it. Her recollections emphasize continuity and ongoing effort rather than singular accomplishments.

Her presence is still visible in Durham. Her portrait of her father greets visitors at the Stanford L. Warren Branch Library. Her hand-drawn map of Hayti preserves the memory of a neighborhood reshaped by time. Issues of The Merrick Washington Magazine survive in collections as evidence of shared labor and sustained commitment.

She once reflected, “My father passed a torch to me which I have never let go out. We are blessed to serve.” The care she carried did not end with her lifetime. It continues in the practices of teaching, memory work, and community stewardship today. On her birthday, we honor the torch she tended and the work that keeps it lit.

Sources and Further Reading:

Dr. Charles DeWitt Watts Papers, David M. Rubenstein Rare Book and Manuscript Library

Includes correspondence, family materials, John Carter Washington materials, and extensive documentation relating to The Negro Braille Magazine and The Merrick Washington Magazine.

Materials relating to Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore in the Rubenstein Library

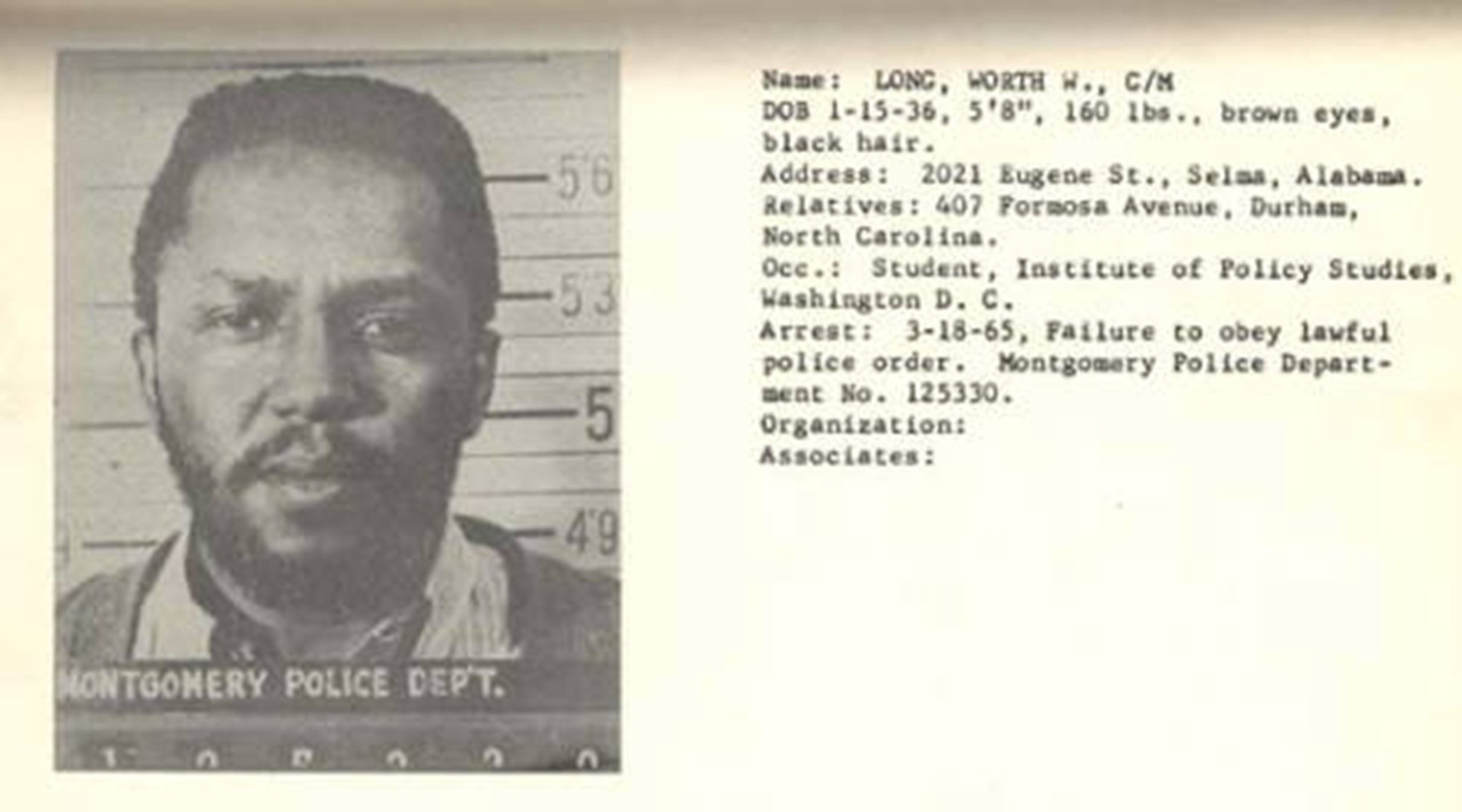

Appearing throughout the C. C. Spaulding Papers and related institutional and family collections.

Hand-drawn map of Hayti by Lyda Moore Merrick

Available through Durham County Library and the Rubenstein Library digital collections.

Portrait of Dr. Aaron McDuffie Moore (1940)

Painted by Lyda Moore Merrick. On display at the Stanford L. Warren Branch Library.

Hope and Dignity: Older Black Women of the South, by Emily Herring Wilson

Temple University Press.

Aaron McDuffie Moore: An African American Physician, Educator, and Founder of Durham’s Black Wall Street (2020), by Blake Hill-Saya

A comprehensive biography of Dr. Moore.