Post contributed by Vincent Carret, Part-time Research Scholar for the Economists’ Papers Archive and Visiting Scholar at the Center for the History of Political Economy.

The Leonid Hurwicz papers are now fully reopened for research as part of the Economists’ Papers Archive. Over the past few months, the bulk of the 252-box collection has been reprocessed by inventorying, describing, and rearranging its contents, in particular the now distinct Research and Writings series. The following blog post describes Hurwicz’s professional trajectory, as it emerged from his papers, and outlines some files present in the collection.

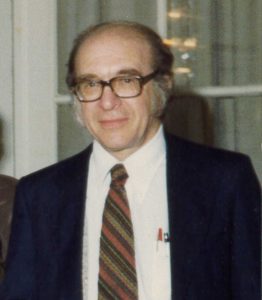

Leonid Hurwicz was a Polish-American economist who immigrated to America in 1940 after fleeing Poland, which is documented in several folders. While Hurwicz never received a diploma in economics, he worked with and learned from some of the most recognized economists during the 1940s. When he arrived in the United States, Hurwicz joined the Cowles Commission for Research in Economics, which had just recently moved to Chicago. The Commission was the major driver in the development of econometrics, a new field of economic inquiry bringing together economic theory, mathematics, and statistics, and Hurwicz participated in the discussions surrounding the use of statistics in economics (collaborating for instance with Theodore Anderson).

At the end of the 1940s, the focus of the Cowles Commission turned to the theory of resource allocation, a field of economics inquiring into the best use of scarce resources in interdependent economic systems. Hurwicz, who was recruited by Walter Heller at the University of Minnesota in 1951, followed this shift. His work during the 1950s focused on the study of abstract market mechanisms, as documented in his collaborations with Kenneth Arrow and Hirofumi Uzawa. One question that became central to his work was the use of information in centralized and decentralized economic systems. Hurwicz built and studied economic models dealing with this problem, leading him to several long-standing collaborations with Thomas Marschak and Stanley Reiter.

During the 1960s, Hurwicz explored new ways of modeling the exchange of information, developing the concept of incentive compatibility to take into account individual agency in the distribution of information. His writings in the early 1970s document these new questions, Hurwicz’s answers, and the tools that he used, including game theory, which was also used to study different institutional arrangements. In the 1980s and 1990s, Hurwicz started working on a book collecting the state of the art on mechanism design, which brought together his interests in decentralization, information, incentives, and institutions. A highly formalized, mathematical endeavor, its theory and applications to auctions have led to several Nobel Prizes, including one for Hurwicz in 2007. His book, Designing Economic Mechanisms, coauthored with Stanley Reiter, was published in 2006.

Hurwicz’s success can be measured by the number of manuscripts preserved in his papers, his many correspondents, and the amount of working papers that he received from colleagues. His success also hinged upon his central place in the Department of Economics at the University of Minnesota, which became a powerhouse of economics in the 1970s-1980s.

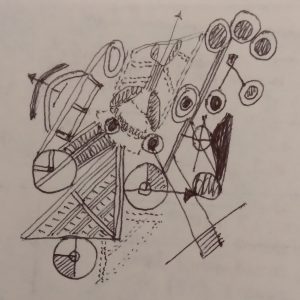

Hurwicz’s work was abstract in a mathematical way, although always related to questions raised by changes in society. Among the most surprising items in the collection, perhaps attesting to Hurwicz’s ability to consider a problem under its most pure and abstract forms, I was amazed to find dozens of doodles that he made while taking notes. “Doodle” does not do justice to the intricate shapes, lines, circles, and points that make up these drawings. Seeing them next to the models and demonstrations that made up Hurwicz’s work, I was reminded of the Italian futurist movement and its celebration of the modern, industrial society. As I learned more about Hurwicz’s interests and work while processing his papers, these drawings became for me a metaphorical illustration of the mutation of economics from “political economy” to “economic science.”