Post contributed by Kelsey Zavelo, Doctoral Candidate in History and Eleonore Jantz Reference Intern 2021-2022.

Chapter 2: Digging Deeper

In my previous post on this blog, I wrote about finding an 1847 letter written by Jacob Chiles, a formerly enslaved person, in the Joseph Ingram Sr. Family papers here at the Rubenstein Library. In his letter, Chiles explains what slavery and freedom meant to him and his family.

This week I dig deeper into Chiles’s story by exploring what other documents in and beyond the Ingram papers can tell us about him.

Donated to the Duke University Library’s Manuscript Department (now the Rubenstein Library) in 1953, the Joseph Ingram Sr. papers includes approximately 1130 items covering 2.5 linear feet. The bulk of the collection consists of family, business, and transactional correspondence as well as bills and receipts, arranged chronologically, primarily dating to the first half of the nineteenth century.

Based on his reference to having spent “some three score years” in bondage, Chiles may have been around sixty years old by the time of his writing. With Chiles’s possible age and surname in mind, a bill of sale dated June 13, 1803 could be the beginning of his paper trail in the Ingram papers.

The bill details the purchase by Joseph Ingram, Sr. of Anson County, “two certain negroes named Jacob and, other named Ruth, and one horse named Ball for the sum of six hundred Dollars” from a friend of the family, Thomas L. Chiles. The purchase agreement included a clause that essentially boils down to a rent-to-buy-back scheme: Chiles agreed to pay Ingram $60/year to hire Jacob and Ruth on an annual basis, with the understanding that if he were to do this for at least 10 years, thereby paying Ingram up to the original $600, Ingram would “return the said negroes to the said Chiles.” It is likely that Jacob Chiles continued to live in close proximity to both families after 1803, which might explain why he kept Chiles as a surname. In his Last Will and Testament dated 1820, Thomas L. Chiles reaffirmed his agreement to sell Jacob to Joseph Ingram, stating, “It is my will and desire that the Bills of sale I gave Jos. Ingram Sr. for Jacob…to stand good…” Perhaps it was only after this time that Jacob came to live permanently on the Ingram plantation.

The John Hope Franklin Center has digitized scores of similar bills of sale and other items documenting the sales, escapes, and emancipations of enslaved people from colonial times through the Civil War. Browse the American Slavery Documents Collection.

In his letter, Chiles mentions that his two sons, one named Walter, started attending Harveysburg High School during their first winter in Ohio. Founded by Quakers Jesse and Elizabeth Harvey—the latter of whom was also an abolitionist—the Harveysburg School was established in 1831 as the first free school for African Americans in Ohio. Since 1977, it has been listed in the National Register of Historic Places as “Harvey, Elizabeth, Free Negro School.” In addition to telling us something about his dreams for his children’s future and possible educational training prior to leaving North Carolina, Chiles’s naming of the school provides a solid foundation upon which historians and others might dig deeper into the historical record to find more traces of him and his family after slavery.

It is unclear how or when Chiles himself learned to read and write. While many enslaved and formerly enslaved persons dictated their messages to sympathetic scribes, evidence suggests that Chiles penned his own letter. The changes in handwriting that accompany changes in tone and emphasis, for example, suggest that the person writing was also the person dictating the message. Additionally, a genealogy of the descendants of Joseph Ingram Sr. (1744-1828) and Winifred (Nelms) Ingram (1752-1841), which was compiled in the 1950s by the Ingrams’s great-great granddaughter, offers the first clue to Chiles’s educational background.

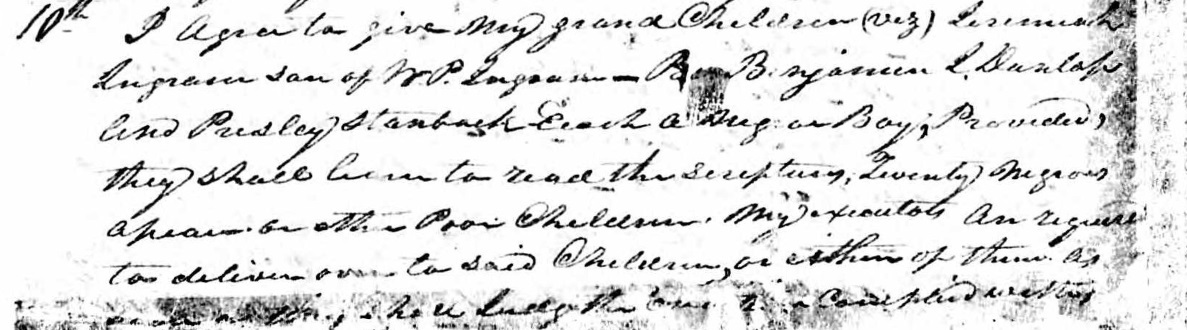

An introductory note to the genealogy mentions that the joint will of Joseph and Winifred Ingram had the following “unusual” feature: “(1) the bequest to their grandchildren…of a Negro slave each ‘on the condition that they shall learn to read the scriptures twenty negroes apiece or other poor children.” Thus, it appears, Joseph and Winnie embedded the teaching of literacy into the family’s (paternalistic) slaveholding and religious ethics by tying the practice to their grandchildren’s inheritances. It is possible that the Ingrams engaged in this practice over the years, teaching many to read and write, including Jacob Chiles and his children.

One of the key principles of doing good historical research is verifying details with primary sources. So, upon reading the note, I hastened to Ancestry.com to see if I could track down a digital copy of the Will. And there it was! including the note regarding literacy, which can be found on page 2 (item 10).

Despite the will, it’s important to note that Chiles’s letter is an anomaly in the records that the Ingram family saved. There do not appear to be any other texts authored by enslaved persons in the collection, nor have I found any contemporary references to teaching literacy. Nevertheless, the possibility remains that Jacob Chiles and other enslaved persons openly learned to read while in bondage. Perhaps this environment made it possible for Chiles’s sons to begin learning to read and write before starting at Harveysburg High.

The same will may also provide a clue about Chiles’s manumission. Starting at the bottom of page 2, in item 13 Joseph Ingram specifies that “it is my desire after the death of my wife…that if such slaves…should prove faithful and obedient to their owners and be [?] capable of taking care of themselves, at the age of Forty years be emancipated so long as they shall continue to be inoffensive and industrious citizens…”

Drafting language making the manumission of enslaved persons conditional upon the subjected person’s ability to prove some form of good “citizenship” was a common practice for nineteenth century slaveholders willing to entertain the practice. It opened a small window of possibility for the enslaved, but one that fundamentally hinged on the new slaveholder’s willingness to carry out the wishes of their dead relative. At the end of the day, a promise of freedom =/= freedom.

Winifred Ingram died in 1841. Jacob Chiles was likely well over forty years old at the time of her death. Without manumission papers, it is difficult to determine when Chiles was freed, and if it was done in accordance with the Ingrams’s will.

Jacob Chiles’s paper trail gets fuzzy beyond his letter, the bill of sale, and a few other suggestive documents. The name Jacob occurs with some regularity in other letters and legal documents in the Ingram papers, but without deep investigation I cannot say for certain which documents refer to the Jacob Chiles. At the end of his own letter to John M. Ingram, for example, Jacob asked that John to do him “one more kindness that is to remember by love to all my brethren in bondage and especially to these that is Isaac, Davy, Sam, Sawyer, my sons Jacob, Jacob, Dock, Alfred, Rickett, & John, Perryan, & Walt begs that you to say Howdy to Jethrum for him & Sandy, Edmond, & Williams respect to Mosey, uncle dick, govenor, Jack Henry, and Ned, Cato Smith, Uncle Solloman & all inquiring friends.” Was Jacob and his wife forced to leave several of their children behind, two of whom might have been named after their father?

I hope to chart new research avenues for recovering more of Jacob and his family’s stories. In the meantime, I am assisting the Rubenstein Library with reprocessing the Joseph Ingram Sr. Papers to add more details to the catalog and collections guide. Adding the names of enslaved persons like Jacob Chiles to the Library’s metadata will help scholars and other library users—perhaps even those in pursuit of family histories—identify more extraordinary stories of the historically subjugated and marginalized.