Post contributed by Kelsey Zavelo, Doctoral Candidate in History and Eleonore Jantz Reference Intern 2021-2022.

Chapter One: Finding the Extraordinary

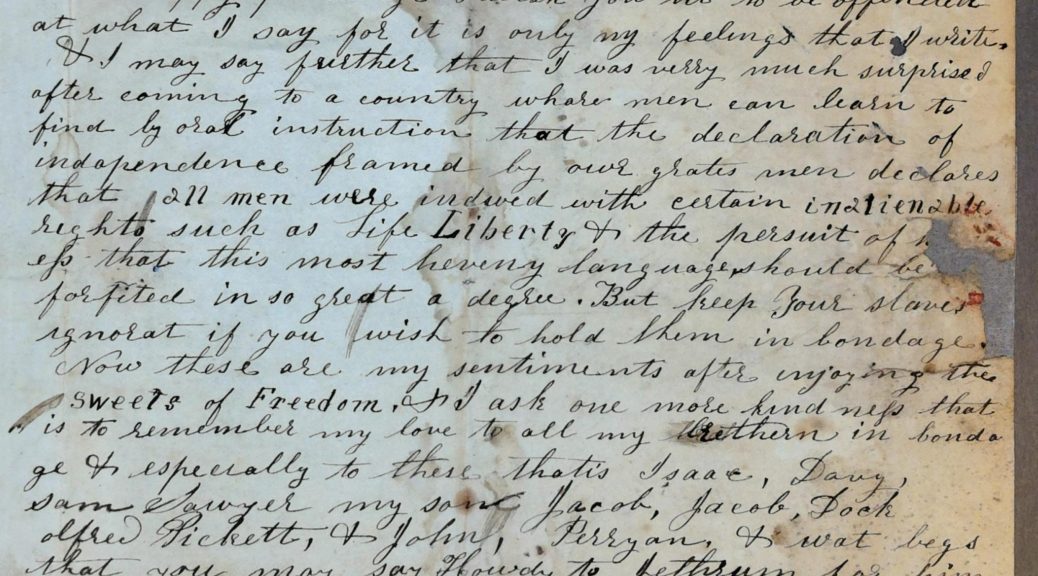

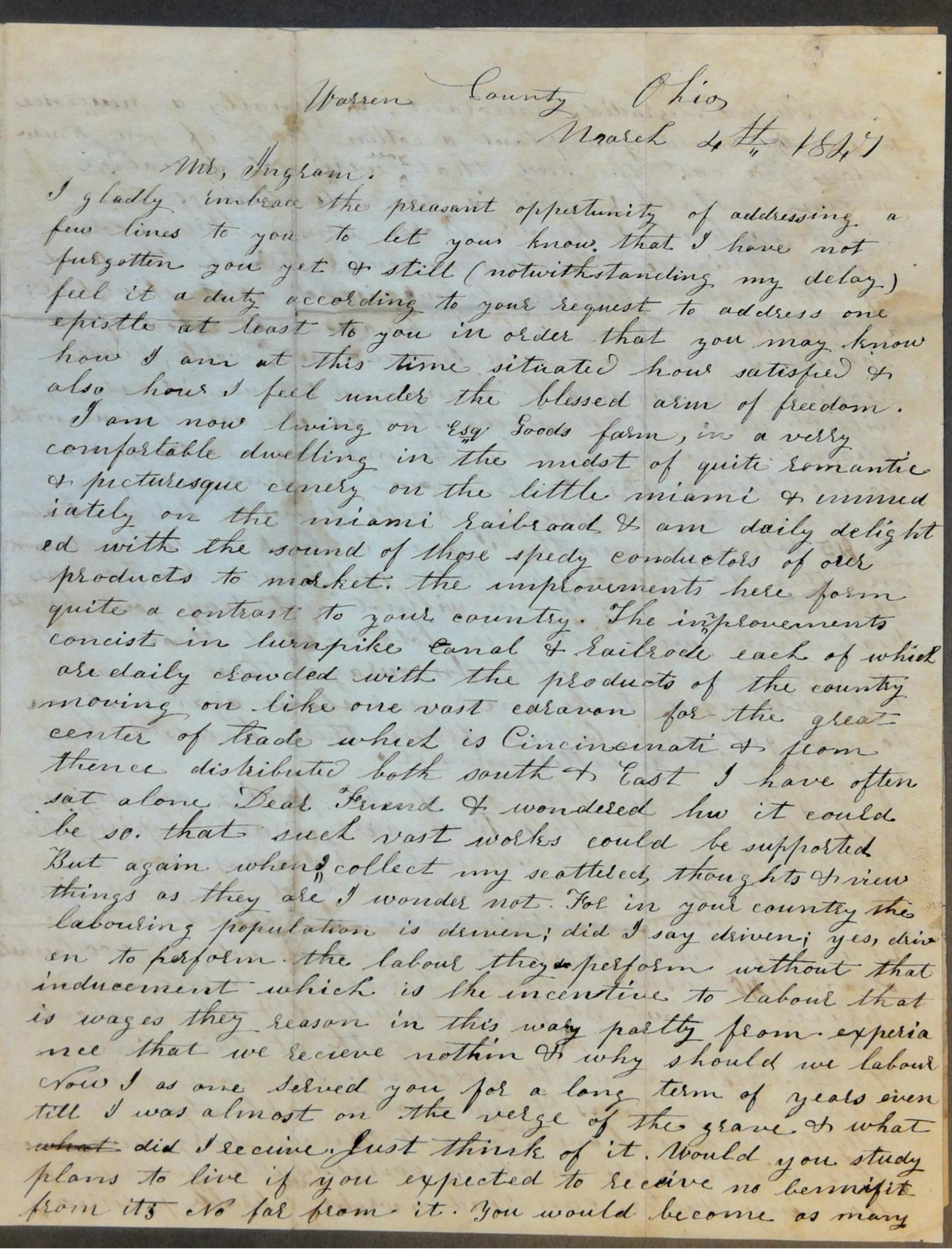

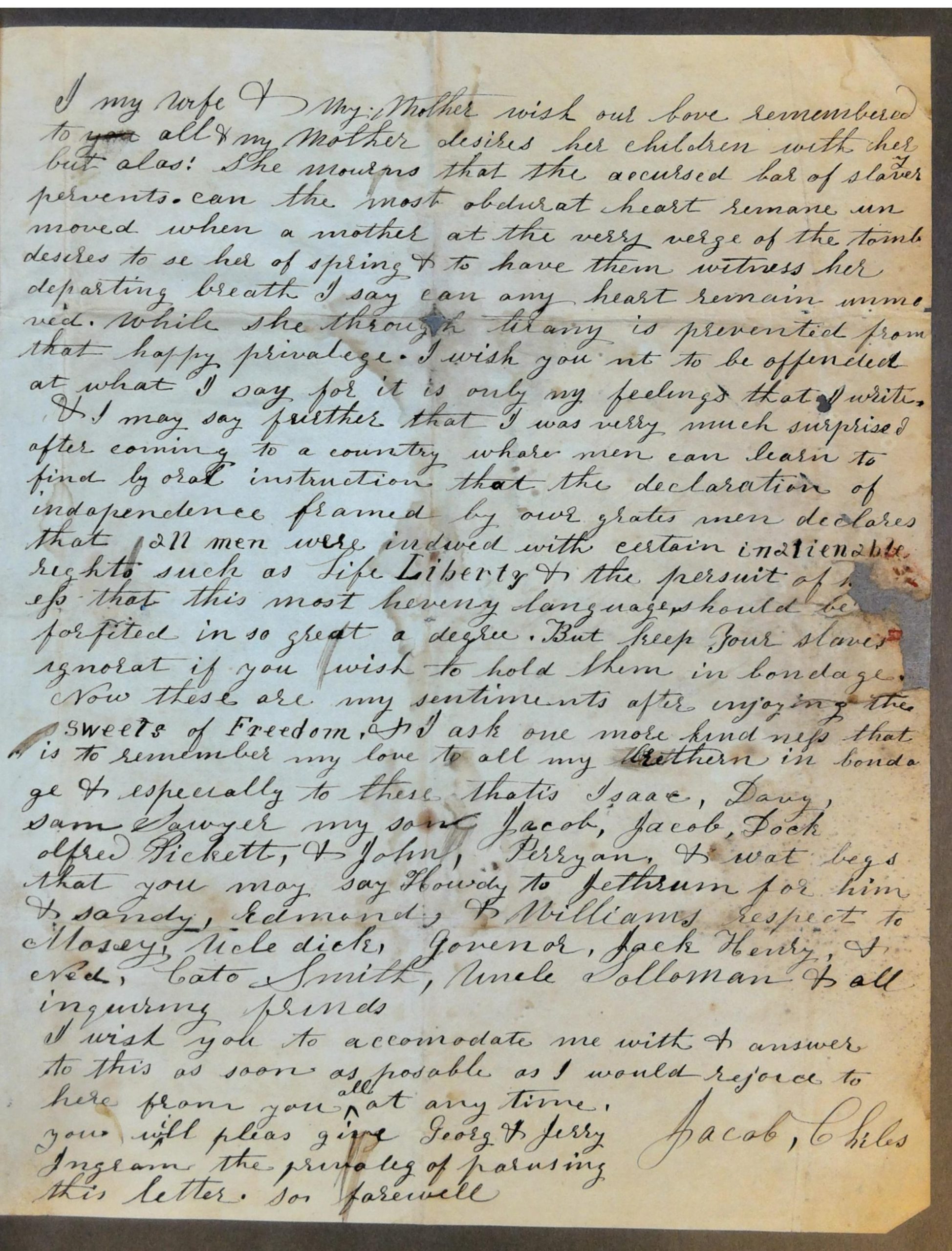

While browsing the Joseph Ingram Sr. papers to answer an ordinary reference question, I came across an extraordinary letter. From his new home in Warren County, Ohio, on March 4, 1847 a man named Jacob Chiles wrote to John M. Ingram of Lilesville, North Carolina to satisfy John’s request that Jacob write him once resettled—in Jacob’s words—”in order that you may know how I feel under the blessed arm of freedom.”

I paused, and I read the line again. “…under the blessed arm of freedom.” At that moment I knew I was reading something special: a letter written by someone special. In 1847, Jacob Chiles was a free man writing to someone who once claimed him as property.

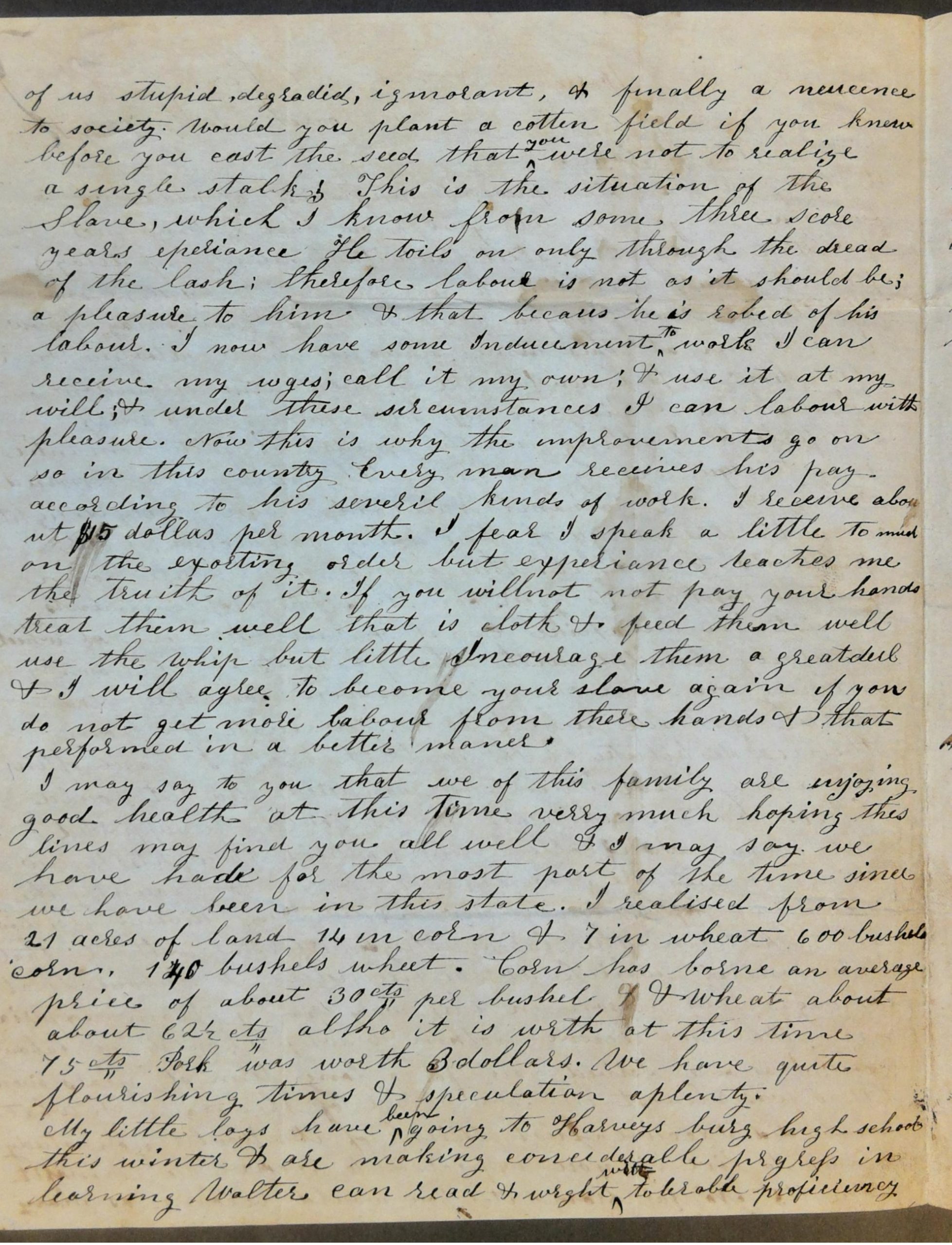

If for no other reason, Jacob’s three-page handwritten letter is remarkable for the simple fact that it exists. Because of the literacy skills and resources needed for their production, letters are historical documents that privilege the retelling of some people’s stories over others’. While letters written by political and social elites, business leaders, literary figures, and other (mainly white) educated adults were common to the US antebellum period, letters penned by enslaved- and formerly-enslaved persons were rare. And while some “slave letters” were transcribed by a literate person on behalf of the author, Jacob appears to have penned his letter himself.

Slave letters were rare, but they do exist. Anti-slavery newspapers reprinted the correspondence and other writings of hundreds of black people who escaped or otherwise left bondage to further the abolitionist cause. Still others, especially persons laboring as house servants, artisans, and drivers wrote—sometimes frequently—to family, friends, masters and mistresses, businesspersons, and others. Published in 1974, 1977 and 1978 respectively, Robert Starobin’s Blacks in Bondage, John W. Blassingame’s Slave Testimony and Randall M. Miller’s “Dear Master” reflect a few historians’ conscious attempts to assemble, analyze, and render accessible a rich sampling of letters by persons that the institution of slavery had intended and functioned to silence. Over the years, researchers and staff at the Rubenstein Library have identified dozens of “slave letters” in across its collections.

The content of the Jacob Chiles letter is as extraordinary as is its materiality; it requires no editorial note. (Take, for instance, Jacob’s personal wager to John about the benefits of wage labor: “If you will not pay your hands[,] treat them well…feed them well[,] use the whip but little[,] incourage [sic] them a great deal & I will agree to become your slave again if you do not get more labour from their hands & and that performed in a better manner.”)

In a coming post [now available], I elaborate on what other documents in the Ingram family papers and beyond may suggest about Jacob’s biography and life in bondage. At this point, I simply implore you, dear reader, to read and contemplate Jacob’s letter, his own words.

You can also download a transcript of the text and PDF scan of the original letter. Read the second post in this series.